Industry Insider | May 2021 Hearing Review

By Karl Strom

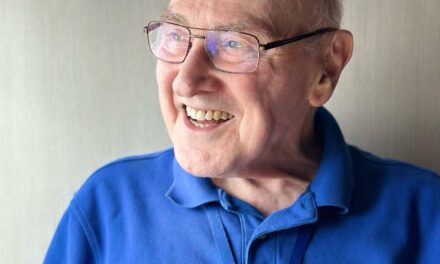

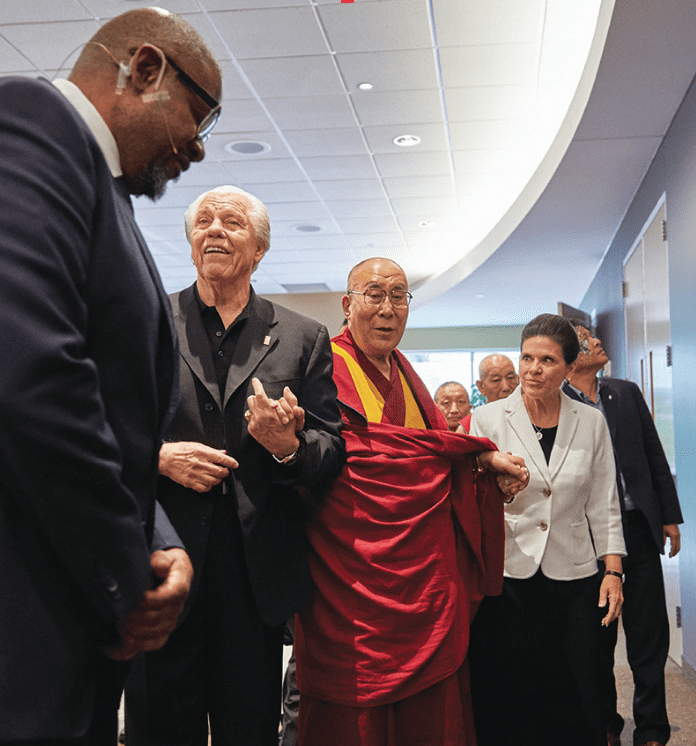

In February, William (Bill) Austin celebrated his 60th year in the hearing healthcare field. Few people have had a better front-row seat to the history of this industry than Austin. Purchasing the small earmold lab in 1970, he built Starkey Labs into one of the largest hearing aid manufacturers in the world and has played a major role in hearing aid dispensing, technology, and industry evolution.

With this impressive anniversary, Hearing Review thought it would be a great time to sit down and chat (via Zoom) with Austin. Part 1 of this article, published in April, looked at how Austin initially entered the field, his purchase of Starkey, and early hearing aid technology.

HR: As you’ve noted [in Part 1 of this article], product life cycles have gone from what were once 3-5 years in the 1990s and 2000s to as short as 12 months today. Is there an argument that, in the past, products featured more dramatic changes when introducing a new model, while today the industry is more marketing driven with an emphasis on incremental changes in the products?

Austin: Well, like I said [in Part 1], I think we are in a race to do better. It’s easy to say something is “new,” and there’s always a presumption that new is better. There have been times in the distant past when a “new model” by the same company might have actually been only marginally better—and perhaps in a couple cases worse—than the previous model. Today, I think that’s rare to nonexistent. And the reason is you need to test extensively the hearing aids on patients in real life—people who have hearing loss—and look for what’s weak in the product, then get that ironed out well before you introduce it. All of this takes time. So, the hearing aids that we’re releasing next year, we’ve been working on [the various new facets] for up to 6 years or so. The product life cycles are changing, but not necessarily the time it takes to develop the devices.

HR: That’s true. We rarely published benchmark-type articles in HR during the 1990s, and few companies published what might be seen as deep dives into an aspect of hearing aid performance. Like you said [in Part 1], a “big innovation” in the past, like a new faceplate, might be a footnote or worth no mention at all today.

Austin: The technology is just so much more different today, and we’re in a very competitive technology-driven market. I mean, [in previous years] we had great ideas, but we could only conceive and talk about them in a very general way. It has been pretty much only in the last 6 years or so—particularly since Achin [Bhowmik, Starkey CTO] has come on board—that we’ve been able to champion many of these far bigger innovations, ideas that I had going back to the 1980s.

As I said, I mostly flow to wherever our company’s issues are—and we don’t, right at the moment, have many issues since things are running very smoothly and very well. Brandon [Sawalich, Starkey President and CEO] is doing a terrific job, and he really is taking care of the company quite well. This takes a lot of additional burden off of me. So now all I have to do is keep working with Achin and our team on the future. That’s the fun part, the eureka moments that are coming that will cause Starkey and our customers to jump up and down.

HR: Since we’re on the subject of technology and looking into the future, where do you see hearing aids going in the future?

Austin: If you’re talking about what we call today the “hearing aid,” then there isn’t a future; the future is in new devices. Certainly, it’s about devices that will compensate for the damaged auditory system, but hearing aids will also help people overcome many other challenges in life so they can do more and be more.

We’re making hearing aids that will be personal assistants. They will include health monitoring features. They will do so many things they don’t do now. And we’re working all the time on expanding what we can do with hearing aids. I’ve been pursuing this for some time, and there has been a sizable gap between when we first talked about many of these things in the 1980s-90s and today. As I said before [in Part 1], I realized I was talking about them too soon—just like with digital signal processing in hearing aids. I recognized we first had to have a DSP platform to accomplish these things. That’s why I started bugging our [engineering team] in 1988-89, and we even called a meeting in a little town in Germany to map out a digital aid that could eventually translate languages and do many things to overcome common barriers to communication.

This is the ground we own. The way I look at it, it belongs to us. We’ve dreamed about it for so long, and I want to see the dream realized, and that’s why I bug my team all the time: “Well, how are we coming? How is this project coming? How is that project coming?”

So, I think a combination of the technology evolving more quickly and bringing new team members on board were the catalysts for [the Livio hearing aid] and all the innovations we’re coming out with now.

There are so many possibilities, an obvious example being our system for detecting falls. However, there are also things like monitoring heart rates, or providing other measures and helpful additions to make life safer, easier, and better not just for older people with hearing loss, but for everybody who wants a more active healthier lifestyle—and that is everybody.

I mean, the ramifications are just wild. We have to succeed. The world needs us to succeed.

HR: With all these new features, I think what sometimes gets lost is the fact that the sound quality has become so much cleaner in the past couple years. I’ve been struck with how this opens up hearing aids to people with near-normal hearing like myself who might just need a little help periodically in noise. So, like you say, hearing care products will be for everybody.

Austin: The sound quality is so much cleaner, better, and more natural. I supposedly have no hearing loss, but I wear Livios. Achin wears his Livio’s all the time, as do other people. My wife, Tani, has normal hearing and prefers to wear them. In the past, if you had normal hearing, you wouldn’t want to wear a hearing aid for more than 5 or 10 minutes because they’d drive you crazy, right? Unless you had a hearing loss, you wouldn’t put up with [the reduced sound quality]. Now it’s like you don’t even notice them. They’re transparent.

So, as a product class, hearing aids have become very different than before, and sound quality is key. That expansion of the existing market from hearing-impaired people to “normal-hearing” people is exciting, not to mention the fact that the number of people needing hearing aids is growing extremely fast due to our aging global population.

I think very soon what we’re now calling hearing aids will become “must have” devices, because they connect you in so many ways, give you direct access to the internet, and provide answers to your questions [via voice-controlled personal assistants] discreetly in your ear. Future models will be able to download languages or a playlist for songs which you might not even need a phone for; you’ll just go out for a run and hear your music.

There are many things coming that will eventually make our devices not a stigma, but a very desirable thing to have—an essential thing to have. Cell phones have become almost essential, right? That’s because of all the things we use them for. I see the same pattern happening in our field.

HR: We talked a little about the custom hearing aid market [in Part 1], which you played arguably the largest role in introducing them to hearing healthcare professionals during the 1970s. However, today we’re seeing RICs and BTEs make up close to 90% of the market. Do you think we’re overprescribing these hearing aid styles or that we may be ignoring the important benefits of custom ITEs?

Austin: Well, you should always do what’s best for the patient. For many, the simple fact is a custom earmold will fit more comfortably and provide better amplification. For some ears and some hearing losses, a standard mold or dome is not the best choice. It’s true you can fit a lot of people well with a standard mold, but you shouldn’t always do that.

Increasingly, we have a lot professionals who haven’t learned or gained enough experience and confidence to take good ear impressions. We need to get that skill back and use [hearing aids with custom earmolds] because patients want them and need them—particularly today. During the pandemic, hearing aid wearers certainly haven’t enjoyed watching their RICs flip into the air and land somewhere in the parking lot when they take off their masks outside the grocery store.

People generally like the idea of in-the-ear hearing aids. Plus, it’s much easier to move forward with the device the patient first envisioned for their hearing loss. What I fear is that, in too many cases, the professional is recommending a RIC and telling them the custom device they want doesn’t have enough power, or it won’t do this, or it won’t do that, because they’re afraid of [custom ITEs]. And, when confronted with the RIC, the patient might say, “Well, I better go home and think about it,” and walk out, and you might not see them again for years, if ever.

The professional might console themselves by thinking, “This person just wasn’t ready yet.” But in a lot of cases, that’s not true. When you miss out on helping them, you failed the patient. If they step in your door, it’s because they’re looking for hearing help. They need your help. And if you don’t provide that help, you failed.

HR: I’d be remiss interviewing you about your early years in the hearing industry if I didn’t ask about hearing aid returns. Our industry’s return-for-credit policy is another “first” that you played a huge role in during the 1970s, and it was quickly adopted by the hearing industry. How did that come about?

Austin: Starkey Labs started out with a return policy [on earmolds] before we even announced our first hearing aids. When I announced our new product, I said our hearing aids must be offered on trial, because people don’t buy a hearing aid, they buy better hearing. The provision of [better hearing], at that particular time in our industry’s history, was unpredictable at best because only the patient could tell you what they heard. Verification equipment didn’t exist and there were few measures outside of “How does that sound?”

My position was that we were doing no one any good if we were ultimately creating unhappy customers. Consumers should be pleased with [our products and the professional services]. So I said we’ll back you up; [hearing care offices] can put these aids out on trial for 90 days. If they don’t work for the client and are returned, we’ll give credit on your account. And we weren’t strict with the 90-day policy; if there was a good reason why the aids had been returned well past the 90 days—say, the people had gone on a trip to Italy or pretty much any other valid excuse—we would honor it. Our policy is not to fight with the customer.

However, the return policy was considered heresy in the industry at that time. A couple well-respected people issued a strongly worded letter that more-or-less advised people not to buy hearing aids from Starkey because of this heresy.

So, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) called me to Washington. Their position was they needed to pass return-for-credit rules so every company in the industry would be required to do what Starkey was doing. I told the FTC, “You’re wasting your time, because before you can promulgate a law, our return policy will become an industry standard simply due to competition.” And that’s exactly what happened. By the time they called me to say they had put together the rules, the industry was already doing it, and Starkey had gone even further with some other policy changes favorable to both the consumer and dispenser.

In my letter to them, I said we treat the patient with hearing loss, not the pocketbook, meaning we’ve always been open to making accommodations to help patients who cannot afford a hearing aid. That was a global policy for Starkey. If someone asked us to help a patient, we tried to do it. In some cases, we might have been cheated by a dealer or swindled by a patient, but I never worried about that. It was better to be cheated than to bury someone in all kinds of forms to see how poor they were or to make things more difficult. We’ve operated that way for years now. I think you’ll see this will become more dynamic in the US with the current problem of travel and Covid-19.

The bottom line is that we instituted policies that I thought were right for the patient and were good for the industry’s reputation. The most valuable thing we have is our reputation. We can’t afford to damage it. That’s our future referral stream and the strongest component of our order base. When we launched the company’s first hearing aid, I sent out this one-page letter saying we’re offering “a custom hearing aid that is worthy of your consideration.” I never said it was wonderful, or that it would outperform all other hearing aids, or even you should buy it; I just said it’s worthy of your consideration and we backed it with a return policy. My main problem for several years was keeping up with orders after that letter.

I remember [publisher] Milt Goldstein of The Hearing Journal wanting to help me out. He liked what I did and he wanted to know more about Starkey. I introduced him to our customer service manager, and told Milt, “He’s the boss.” Milt asked, “What about sales?” and I said, “My idea of sales is customer service. People don’t want to be sold, they want to be helped, and you’ll be blessed with orders if you give them what they really want.”

That was hard for him to understand. At that time, you never heard much about customer service. It was before the word was regularly used by Sears, Montgomery Ward, and other stores. Companies weren’t using customer service as a primary market position, and I think we were really the first in our industry to do so. We were also the first company to computerize our records in the 1970s. Even before we bought Starkey, we had started that process and we designed the best computer system you can imagine to help serve customers.

It certainly wasn’t what the accountants wanted. We told them we didn’t care if it takes you two months to close the books; you just tell us if we’re running short on money.

HR: In meeting with your staff through the years, I’m struck with how many industry legends you’ve employed. For example, when I first came into the field about 25 years ago, Starkey employed people like Jim Curran, Earl Harford, David Preves, Dale Thorstad, Jerry Agnew, and many other bona fide “all-stars” in hearing care. And through the decades you’ve managed to keep hiring extremely prominent audiologists, engineers, and executives. You mentioned [in Part 1] that you bought Starkey primarily because of Paul Jensen, who was the best earmold fabricator you’d ever seen to that point. Was that the start of this tradition?

Austin: Starkey has been very fortunate to attract highly talented people and, of course, that has contributed greatly to our success. When I think back to the early ‘70s, we hired what I considered the best engineer of that time, Bill Ely. One of the best audiologists of that time was Terry Griffing who had worked at the Mayo Clinic, then worked at Qualitone prior to us hiring him. The goal, of course, is to find people who will make us better and ultimately help more people who have hearing loss.

But I found that the real strength of Starkey was not finding or hiring a Superman, because that’s a myth. There aren’t any. The goal is to hire regular people who smile when they work, want to be part of something—not just an individual star—and can work together as a team to be part of a gift to our community and find great satisfaction in that teamwork. If they felt that way, if they were philosophically in-tune with Starkey, they became great employees.

From the early days, I’d look at potential employees to recruit, and I’d try to see if they were happy in their work and positive about the things they were doing. Some of them had major weak points. They were spectacular in this one particular area, but not very good in this facet or in that facet, right? That’s human nature. I didn’t worry about their weaknesses; I cared about what they could do. That’s where the strength of the team matters, because we can cover weaknesses with other people who are better in those missing facets.

If you dwell on the negatives and what’s wrong, you discover failure and despair. If you take the time to find out what’s right, you can blaze a path to success for most people. So, I look for the talent and what’s right with people. And we’ve tried to make regular people better, not turn them into “super-people.”

The truth is we’ve been able to get super performance out of regular people. Some in the industry thought, “Oh, if we could only hire this person or that person from Starkey, that’s the key to Starkey’s success.” That’s not true. The key to our success was the acceptance of the key values worth pursuing and worth being a part of. That comes right back to being happy with your work and being a good member of the team. My best employees weren’t obsessed with how much money they were going to make; they were too excited about what they were doing and having the chance to work within our team. Because if they did work well with the team, no matter what kinds of faults or weaknesses they had, they wouldn’t be under such great pressure or be prone to failure, and they’d be well rewarded…The goal has been to allow a person to find their area of greatest contribution. It’s that simple.

HR: I’ve also been impressed with the autonomy Starkey employees are given. I remember Earl Harford telling me that the Starkey Internship Program—the first student program established in our industry and one I thought was brilliant—began after he mentioned it to you and you just told him to go do it.

Austin: That’s true. Even some projects that I personally do not agree with, or I don’t see how they’re going to be very successful, are worthy of pursuing if a person has the passion. Because if people have passion, they’ll do better, they’ll get more done. And, if it doesn’t pan out, it won’t hurt us because they’re doing it with good spirit. So, within reason, I’m very much in line with letting people do things and pursue objectives. In that particular case, Earl was very excited about an internship program. So that was fine. I let him do it. I certainly knew it wouldn’t hurt us. Again, you keep looking for the positives and for how we might make progress, not for the negatives or what might be wrong with an idea.

HR: It’s a fact that Starkey has become a technology-driven company. However, when people ask me specifically about Bill Austin, I tell them you’ve always seemed to have a knack for being able to understand what dispensing professionals need even before they might have been able to articulate that need for themselves. So, given the changing technology and our dynamic field, what do you think hearing care professionals should be doing to prepare their businesses for the future?

Austin: As I said before, you really need to love your work and smile when you’re doing it. If you really want to succeed, you first need to find your motivation. In our business, you have to care about your patients. They don’t want to be sold; they want to be cared about. Ultimately, we’re in a caring profession, and the professional needs to care enough to do their very best every time. They need to take a personal interest in each individual patient and make sure that patient’s hearing potential is maximized, and that the person understands the product and takes full advantage of it.

So, what do you need to do if you want to be successful, now and in the future? You need to work hard and be good at whatever you do. That applies to everything. If you’re not happy in your work, you won’t be smiling, and you won’t do as well, right? You won’t be accessible.

Ultimately, you have to really like helping people, really care about the patients you see, and find great satisfaction in doing it. If you feel that way and you keep trying to do better, then you will get better and become a tremendous provider. The motivation comes first. You learn from trying to do the job. People learn much better that way than they do by reading books. If you acquire the kind of skills and training a seasoned hearing care professional has, and you’re motivated to help people and work hard at it, you’re going to do very well in the future by simply doing what is right for the patient.

There are so many people with hearing-related problems that can be helped with hearing aids and our future devices. We’re at an amazing junction in our professions, our technology, and our industry. Become great at providing care for your patients, and I don’t see anything that would prevent you from being successful.

Citation for this article: Strom K. Philosophy of growth by serving people’s hearing needs: An interview with Bill Austin, Part 2. Hearing Review. 2021;28(5):27-30

Correspondence to Karl Strom at: [email protected].