By John Duffy, PhD

A few of the many significant contributions to the River of Audiology that can be traced to Robert West, PhD, and the Brooklyn College Department of Audiology, Arts and Sciences, Program of Speech, Language, and Pathology.

The headwaters of the Mississippi River are located in Northern Minnesota. From small streams and from many tributaries this mighty river grows. In a neighboring state, a significant tributary to another river, the River of Audiology, began at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, through Robert West, PhD.

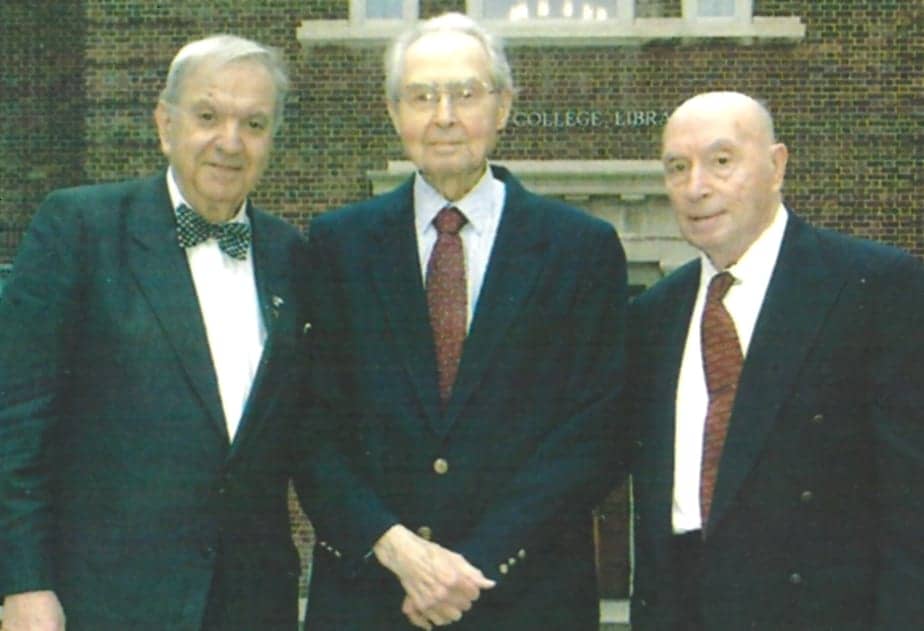

Maurice Miller, PhD, John Duffy, PhD, and Earnest Zelnick, PhD (not pictured: Mark Ross, PhD, and Frederick N. Martin, PhD)

West, an audiological pioneer, was a founder and the first president of what is now the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). He was also an accomplished scholar, well versed in physics, electronics, anatomy, physiology, Greek, Latin, and literature. Beside his PhD degree, West had taken all of the academic courses for a MD degree at the University of Wisconsin Medical School.

I was very fortunate to be one of West’s students. As an undergraduate student in the late 1930s, I was present when West, along with Merle Ansberry, a doctoral student, demonstrated the instrumentation and procedure that he had devised to perform sound-field audiometry. These instruments included an audiometer, an audio amplifier, a loud speaker, and a sound absorbent room. Sound-field audiometry was used to measure the frequency and intensity of tones generated by an audiometer, then amplified and emitted into an open space through a loudspeaker.

The Rayovac Battery Company, with its headquarters in Madison, made the first wearable electronic hearing aid. Their chief electronics engineer, Arthur Wengel, had built an audio amplifier powered by Rayovac flashlight batteries. The microphone, amplifier, and batteries were placed in a small box, and earphones were connected to the amplifier.

West was the first person with his sound-field instrumentation to evaluate Wengel’s hearing aid when worn by a child. Along with other members of West’s class, I watched and heard the testing from an observation room through a one-way window. A 6-year-old boy had been given an audiometric test prior to testing. We matched and heard the sound-field testing of tones from low tones to high tones as the boy responded to them without the hearing aid and then with the hearing aid.

West believed that a hearing aid should amplify the sounds in the frequencies where the loss in the subject’s hearing was greatest in order to compensate for the hearing loss rather than to make all the speech sounds louder. The testing of the 6-year-old boy demonstrated the use of sound-field audiometry to measure whether or not the frequency responses of the hearing aid he was wearing were appropriate. Selecting the appropriate amplification characteristics of a hearing aid is now referred to as “selective amplification.”

In 1944, because West had placed my name on the US Defense Department’s roster of Technical and Professional Personnel, I was transferred to the Army’s Hearing Rehabilitation Center at Borden General Hospital, Chicasha, Okla. I became an instructor and supervisor of auditory and auditory-visual speech perception training and speech conservation.

The hearing rehabilitation center at Borden was a model for the future. It had medical services, hearing testing, hearing aid selection, and evaluation through sound-field tonal and speech audiometry, auditory training, lip (speech) reading, auditory-visual speech recognition, and perception training.

In 1948, I left the Bureau for Handicapped Children to complete my doctoral dissertation. I chose a subject suggested by West. He proposed that a piece of magnetized metal embedded in the mastoid process over the cochlea of a human ear, if made to vibrate because of a fluctuating magnetic field surrounding it, might be more effective as a means of transmitting audio-frequency vibrations to the cochlea than the conventional air- and bone-conduction hearing aid receivers that were then being used.

In order to pursue this theory as a thesis, the problems in need of resolution were: 1) To develop a magnetic field generator capable of actuating a magnetized metal plate embedded in the mastoid process of a hearing-impaired person when such an actuator is being driven by a commercial hearing aid; 2) To discover a subject willing to undergo the operation necessary to implant a magnetic-metal plate in the mastoid bone; and 3) To find a suitable means of implanting a magnetic-metal plate in human bone.

In an attempt to solve the first problem, Samuel F. Lybarger, chief designer and manufacturer of Radioear hearing aids (E.A. Myers and Sons Co), designed and constructed the magnetic field generator (actuator) used in the research. He provided the Radioear hearing aids used for my research, and gave generously of his time and knowledge to the study. (For more information on Lybarger, see the August 1994 HR Living Legends article.)

For the second and third problems, a 45-year-old woman with a bilateral conductive loss of hearing agreed to be the subject for the research and to undergo the operation necessary to implant a magnetic-plate (gold-plated alnicko V) in the mastoid bone. For a few days after the magnetic-coupled bone-conduction receiver had been tightly embedded in the mastoid bone, the bone conduction hearing aid amplified speech with surprising clarity, much to the satisfaction of the subject and myself. This success, however, was brief. The area surrounding the implant became swollen and when the plate was removed it was wrapped in granulation tissue. The implant had been rejected.

To compare the responses of the bone conduction receiver with the magnetic coupled receiver, the sounds from the magnetic coupled receiver were delivered with transmission via the upper teeth. The responses from this delivery system were of higher fidelity in terms of sine wave characteristics for individual frequencies in the range of frequencies considered most important for perceiving speech compared to conventional bone-conduction and air-conduction receivers. Also, the frequency response curves through this same range of frequencies showed the magnetic-coupled receiver responses to be much better than they were for the other two receivers.

The magnetic field emanating from the pole pieces of the actuator/receiver sets the armature into mechanical vibration. When the armature is in contact with the bones of the skull, its actuation results in high-fidelity bone conduction of sound and accounts for the high quality of performance of the magnetic-coupled bone-conduction receiver. According to the subjective judgement of the woman, the magnetic-coupled receiver seemed the most natural; the bone-conduction receiver was next in naturalness; and the air-conduction receiver was the least natural and the least desirable.

The problem of attaching the magnetic-coupler to the mastoid bone was eventually solved with a small titanium fixture placed on the skull bone behind the ear. This occurred 31 years after our research. In 1996 (50 years after our research) the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the BAHA® (Bone Anchored Hearing Aid), manufactured by Entific Medical Systems, Powell, Ohio, for use in cases of conductive or mixed hearing losses due to a poorly functioning ear canal or middle ear. Three years later, the indications for use were extended to include treatment for children ages 5 and over. Through newly expanded indications, BAHA recently received clearance from the FDA for use in patients with Single-Sided Deafness (SSD). With the BAHA systems, sound is transferred from the sound processor via an external abutment to a small titanium fixture placed on the skull bone behind the ear. Placement of the fixture and abutment in the bone is a minor surgical procedure that is performed with the patient under local anesthesia. The success of this system validates the magnetic-coupled bone-conduction hearing aid concept that was conceived 50 years earlier by West.

While I was completing courses for my doctorate degree, West recommended me to Professor James O’Neil, chairman of the Department of Speech at Brooklyn College, to fill a position for an assistant professor. It was then that I began my 34-year-old career at Brooklyn College.

At this time, there was no college or university in the New York metropolitan area that offered a course of study devoted entirely to hearing disorders and hearing rehabilitation. In the spring of 1950, I began such a program. From an introductory course, other courses were gradually added to the speech and hearing curriculum. By this time, the field of hearing disorders had been given a scientific name, “Audiology,” from the latin words “Audire” (to hear) and “ology” (science). In the summer of 1950, West left the University of Wisconsin and joined the faculty of Brooklyn College Speech Department as Professor and Director of the Speech and Hearing Program. With his presence, the stature of the Brooklyn College Speech and Hearing Program was greatly enhanced. He retired in 1963.

Mary Huber, PhD, a colleague in the speech and hearing disorder field, was the speech consultant for the cerebral palsy treatment center at Lenox Hill Hospital in Manhattan. Because a number of the children being treated at the hospital had impaired hearing, she invited me to test them and follow up on their hearing aids and habilitation needs. Learning of my involvement with the cerebral palsy program, the director of otolaryngology at the hospital asked me to establish a speech and hearing center at Lenox Hill Hospital. I was pleased to accept this invitation because it would give me a hospital affiliation that would provide our students with a place for clinical practice and employment opportunities.

West’s Tributary Flows On

Through his dedication and passion for audiology, West guided and influenced many individuals to achieve their own success in the hearing care field. Unfortunately, due to space limitations, it is impossible to list all of the extremely gifted and talented audiologists who were influenced by West. However, I believe the following four individuals are representative of those who have made strong impacts in audiology, all inspired by the early contributions to the field from West and Brooklyn College.

Maurice H. Miller, PhD, was the first Brooklyn College graduate to join West’s tributary to the River of Audiology. He was the first speech and hearing therapist employed for the new center at Lenox Hill Hospital, New York. Miller was an outstanding student who was finishing his undergraduate courses and was working on his masters degree at Brooklyn College. Although he served patients from the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) clinic, the great majority of his patients were children with severe hearing impairment. Providing hearing aids, and hearing and speech habilitation to children with impaired hearing eventually became the primary mission of the center.

After completing his master’s degree, Miller left Lenox Hill Hospital and held positions at two army hospitals, after which he became the director of the Speech and Hearing Clinic at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in Manhattan. While at Columbia, he obtained his doctorate degree in audiology.

Miller became the director of the first multi-disciplined Center for Communication Disorders at Kings County Hospital Center in Brooklyn. He also directed the audiology centers at New York University Medical Center and Lenox Hill Hospital. He is presently a professor of audiology and speech-language pathology at the Steinhardt School of Education at New York University. In May 2002, Miller was awarded the New York University School of Education Teacher of the Year-Teachers Excellence Award for 2001-2002.

During his career, Miller has published over 140 scholarly articles in peer-reviewed journals, five books, numerous monographs, and chapters in widely used textbooks. His two special issues for The Hearing Review on occupational hearing conservation (September 1999) and sudden sensorineural hearing loss (December 2003) are widely used in audiology curriculums across the US. He is an authority on the audiological aspects of tinnitus. A prodigious scholar, he is quoted in the print media, and has been interviewed on radio and television on the subjects of noise, hearing loss, hearing aids, pediatric, and geriatric hearing impairments. He is the first audiologist in the United States to be elected President of the Council for Accreditation in Occupational Hearing Conservation.

In 1996, Miller received the American Academy of Audiology’s (AAA) second Career Award in Hearing for his distinguished career in audiology spanning 40 years in teaching, research, and clinical service. He thanked West, among the teachers whom he stated helped cultivate and expand his interests, and moved him in positive and productive directions. According to Miller, West knew more about audiology and hearing than most other practitioners of his generation.

Mark Ross, PhD, received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Brooklyn College, and his doctorate degree from Stanford University. His master’s degree thesis was titled “Validation and use of pure tones in a sound field.” At the 1961 Annual Convention of the American Hearing and Speech Association, he presented the first paper devoted to West’s sound-field audiometry entitled “Clinical uses of pure-tone sound-field audiometry.”

Later, Ross became a clinical audiologist at the Veterans Administration in San Francisco. He also taught at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, Conn, and worked 2 days a week as a clinician at Hartford Hospital and Newington Children’s Hospital in Connecticut. He left the university after 10 years to direct the Willie Ross School for the Deaf in Longmeadow, Mass, and then returned to the University of Connecticut for 3 years. (For more information, see Ross’ September 2001 article “Aural Rehabilitation: Some Personal and Professional Reflection.)

Ross’s awards include ASHA’s Frank R. Kleffner Lifetime Clinical Career Award, the Honors of the Connecticut Speech and Hearing Association and the Academy of Aural Rehabilitation, the Frederick Berg Award from the Educational Audiology Association, the Oticon Focus-on-People Professional achievement award, the Career Award from AAA, and the Lifetime Achievement award from the American Auditory Society.

He retired from the university and for 5 years was the director of research and training at the League for Hard of Hearing in New York City. He then got heavily involved in consumer affairs, serving on the Board of Self Help for Hard of Hearing (SHHH) for 8 years. He also served on the Board of International Federation of Hard of Hearing and edited their journal for 6 years. For the last 8 years, Mark has written a regular column for the SHHH Journal, Hearing Loss, and, for the last 4 years, Volta Voices. He is also a frequent contributor to The Hearing Review.

Few members of our profession have had such a positive influence on hearing habilitation and aural rehabilitation. Acknowledging the impact that West made on his career, Ross wrote in a letter, “ West was a major influence in our lives. I still recall that he got me into Stanford with a one-sentence letter of recommendation. West’s presence was the most imposing of anyone I’ve ever met in the field.”

In 1955, after completing a 4-year enlistment in the US Air Force, Frederick N. Martin, PhD, returned to complete his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Brooklyn College, and began his career as a clinical audiologist. After 9 years as a full-time clinician, he returned to graduate school to complete his doctorate degree at City University of New York. His thesis entitled “The affects of selective amplification on speech perception,” was inspired by West. He then joined the faculty at the University of Texas at Austin, where he continues his interests in clinical audiology, teaching, and research. He was named the Lillie Hage Jamail Centennial Professor in Communications Sciences and Disorders in 1982.

His publications include 12 single-authorized books, 4 co-authored books, 20 edited books, 20 book chapters, 118 journal articles, 100 conference and convention papers, and several monographs. He has served as a consulting editor for most of the major journals in audiology and, for a number of years, co-edited the professional journal Audiology. Martin has won the Teaching Excellence Award of the College of Communication, the Graduate Teaching Award, and the Advisor’s Award of the Ex-Students’ Association of the University of Texas. In 1997, he received the Career Award in Hearing from the AAA. He is a past president and vice president of the Arkansas Speech and Hearing Association.

Perhaps Martin’s most significant contribution to our profession is his textbook, Introduction to Audiology. This book, first published in 1975, is now in its eighth edition. (John Greer Clark, PhD, became coauthor for the seventh and eight editions, as well as the fifth edition of the review manual.) Introduction to Audiology is among the most popular and widely used audiology textbooks published in the United States.

Ernest Zelnick, PhD, received his bachelor’s degree from Brooklyn College. After military service, he received a law degree at St. John University, Jamaica, NY, and practiced law for a while, but then took over a surgical supply company, which he converted into a hearing aid sales and service business.

With limited knowledge in the field of hearing, he decided to take courses in hearing disorders and rehabilitation at Brooklyn College. Before the term was over, his plan to attend classes for only one semester had changed; he stayed on to receive a master’s degree in speech and hearing, and later he received his doctorate degree in audiology from The Graduate Center of The City University of New York.

It should be noted that, before this time, ASHA considered it “unethical” for its members to sell hearing aids, stating that an audiologist was a specialist who could test hearing and select hearing aids, but could not dispense them. Zelnick was, to our knowledge, the first hearing aid dispenser in the United States to receive a doctorate degree in Audiology. By this time, ASHA had changed its position on dispensing, and decided that it was “virtuous” to dispense hearing aids.

Because of his qualifications and experience as a dispensing audiologist, Zelnick was selected to give courses in hearing aid selection and evaluation at the Technical College of The City University of New York. He conducted these courses for 16 years. The Hearing Journal listed Zelnick in its November 1997 issue as one of the 10 people most responsible for hearing aid selection and evaluation becoming a recognized discipline.

In the early years of hearing aid use, it was common practice to place the hearing aid on only the impaired ear which received the most help from the hearing aid. By the 1960s, binaural hearing aids commanded attention, and this stimulated research to determine their effectiveness. One of the foremost researchers on this topic was Zelnick. For his doctoral dissertation, he did a thorough study of the contraindications and indications for binaural hearing aid selection. A report of his research appeared in the Journal of Auditory Research in 1970 titled, “Comparison of Speech Perception Utilizing Monotic (Monaural) and Dicotic (Binaural) Listening.”

Zelnick’s textbook, Hearing Instrument—Selection and Evaluation, was published by the National Institute for Hearing Instrument Studies in 1987, and is widely used by hearing instrument specialists. Zelnick was the editor of the book and wrote the first two chapters. Zelnick is credited with being a strong influence internationally in promoting the use of binaural hearing aids.

We have traced West’s early tributary to the River of Audiology from its head-waters at the University of Wisconsin to Brooklyn College. At Brooklyn College, the tributaries of myself, Miller, Ross, Martin, and Zelnick—along with countless other fine professionals, instructors, and researchers—joined West’s current to the mainstream of the River of Audiology.

While writing this history I experienced a renewed appreciation and respect for Brooklyn College, for the many ways it has enabled all of us to grow professionally in the audiology field.

Correspondence can be addressed to John K. Duffy, PhD, 41 Amherst Rd, Port Washington, NY 11050; email: [email protected].