Study suggests remote-mic hearing aids offer another custom alternative for new users

This study compares the remote-microphone (RM) hearing aid to completely-in-the-canal (CIC) and behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aid styles for cosmetic appeal, occlusion, comfort, and performance among a group of younger adults with active lifestyles. Although BTEs came out slightly ahead in terms of speech-in-noise and speech-in-quiet scores, only 5 of the 12 new users ultimately selected a BTE, while 4 chose the RM hearing aid and 3 chose the CIC.

Large-scale MarkeTrak surveys on hearing aid use and satisfaction have revealed that aesthetics, comfort, and sound quality have a strong influence on the acceptance of hearing aids, particularly for first-time hearing aid users.1,2 Since their introduction in the 1980s, in-the-ear (ITE) instruments were the fitting of choice for patients with mild-to-moderate impairments, primarily for cosmetic reasons.

Kim L. Block, AuD, is currently an audiologist at Cornerstone Ear, Nose & Throat in Charlotte, NC. Previously, she held a position as a research audiologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. Mary T. Cord, AuD, is a research audiologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

Despite the high cosmetic appeal, ITE devices have often been rejected due to occlusion and comfort issues. Earlier in this decade, the introduction of smaller behind-the-ear (BTE) devices transformed hearing aid fittings due to their discreet appearance coupled with a versatile fitting range and open-ear fitting possibilities. However, some users report difficulty retaining the BTEs on their ears, problems with excessive wind noise due to the location of the microphone, or physical discomfort with the BTE fitting. Also, some patients are displeased with the appearance of any BTE hearing aid no matter how small the size.

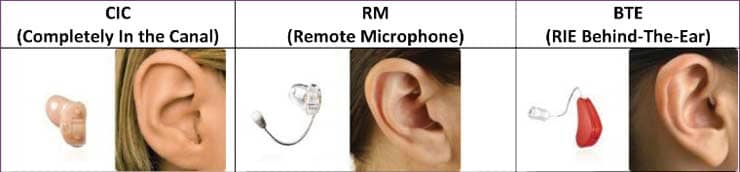

Additionally, there is some evidence to suggest that the BTE microphone location may alter spatial hearing cues.3,4 Recently, a new style of hearing aid, referred to as a “remote microphone” device, has been introduced in which the body of the hearing aid sits in the ear canal and an external microphone sits in the concha cymba of the ear. This design is purported to reduce wind noise, improve retention, and increase cosmetic appeal relative to a BTE, and to reduce occlusion relative to an ITE because a larger air vent is possible.5The purpose of this study was to compare the remote-microphone (RM) hearing aid to completely-in-the-canal (CIC) and BTE hearing aid styles for cosmetic appeal, occlusion, comfort, and performance among a group of younger adults with active lifestyles.

Figure 1. Mean audiogram for 12 participants. Error bars in this and subsequent figures indicate 1 standard deviation.

Subjects and Methods

A total of 12 adults with mild-to-moderate acquired sensorineural hearing loss and no prior experience with amplification were recruited from the patient population of the Walter Reed Audiology Clinic. The 7 males and 5 females ranged in age from 47 to 69 years (average 57.9). The participant group consisted of 3 active-duty military, 5 retired military, and 4 military family members. All participants were employed outside the home, and reported active lifestyles with significant communication demands. Volunteers were excluded if their ear canals were judged to be too small to accommodate custom hearing aid components. Participants were offered a choice of a $200 payment or their preferred hearing aids at no cost as compensation for completing the study.

Methods. Participants underwent consecutive field trials to compare bilaterally fitted custom CIC, custom RM, and receiver-in-the-canal (RIC) BTE hearing aid fittings from the GN ReSound Live™ series. All hearing aids were fit in the default fully adaptive mode. The directional microphones in the BTEs were set to the default, which is Natural Directionality (one ear is set to omnidirectional processing and the other ear is set to a fixed hypercardioid directional pattern). The thin-tube BTE devices were fit to participants’ ears with appropriately sized soft non-custom domes.

Figure 2. The three styles of hearing aids evaluated in this study.

The three fittings were evaluated in a counterbalanced order. Participants wore each pair of devices for 1 week. At the conclusion of each trial week, participants underwent laboratory evaluations of performance, and completed a questionnaire related to their satisfaction with that week’s hearing aid fitting. Finally, at the end of the study, they were asked to rank the devices in order of overall preference.

In an attempt to minimize bias, participants were not shown the devices until each fitting. Neither were they informed about the potential advantages or disadvantages of each style.

Participation in the study required six clinic visits over a 7- to 8-week period. During the first visit, ear impressions were taken for the CIC and RM hearing aids, and participants completed a questionnaire (Hearing Aid Acceptance Questionnaire [HAAQ]) regarding their unaided communication abilities.

When the hearing aids arrived from the manufacturer, the participant returned to the clinic to be fit with one of the three devices, according to the pre-determined randomization order. The manufacturer’s first-fit was used to program the hearing aids, and adjustments were made based on patient feedback and real-ear verification measures. These settings were programmed into Memory 1 of the hearing aids, and all other memories were deactivated. Use and care of the new hearing aids were reviewed and the participant left for a 1-week adaptation period.

When they returned for the third visit, fine-tuning adjustments were made as needed and real-ear verification was repeated if adjustments were made. The subject was then released for the 1-week field trial to assess the first hearing aid fitting. At the end of that week, the participant returned to complete the Hearing in Noise Test (HINT)6 and the aided portion of the HAAQ, after which the participant was fitted with the next set of hearing aids. For each fitting, minor programming changes were made as required, based on patient feedback. The same procedures used for the first fitting were repeated for the second and third sets of hearing aids. Figure 3 displays the mean real-ear aided response of the three fittings, averaged across the right and left ears of the 12 participants.

Figure 3. Real-ear aided response averaged across right and left ears of the 12 participants.

Hearing in Noise Test. The HINT was used to evaluate speech understanding in noise and spatial release from masking. Spatial release from masking or “spatial benefit” refers to the benefit that occurs when speech and background noise are separated in space (ie, presented from different loudspeaker locations) compared to a condition where speech and background noise are co-located (ie, originating from the same loudspeaker). This was of particular interest because a primary difference between the three fittings is the location of the microphone, which may affect important spatial cues.

The HINT uses an adaptive method to determine the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at which the stimulus sentences are identified correctly 50% of the time. Noise with a long-term spectrum matching the average spectrum of the sentences is used as the masker. Noise is presented at a fixed 65 dBA level and the sentence levels are varied depending on the accuracy of the listener’s response.

The participant was seated in a sound-treated booth facing a loudspeaker located at 0° azimuth. A 12-item practice list was presented, and then 20-item test lists were administered in three different noise conditions: diffuse noise (from loudspeakers at 90°, 180°, and 270° azimuth); noise from the front (loudspeaker at 0° azimuth); and noise directly from the right (loudspeaker at 90° azimuth). Standard HINT testing procedures were used.

Figure 4. Mean HINT results for speech in diffuse noise. Note that Y axis is reversed so that higher bars indicate better performance.

Hearing Aid Acceptance Questionnaire. The HAAQ was developed specifically for this study to evaluate participants’ overall acceptance of each hearing aid fitting. Questions focus on the participant’s subjective opinion regarding cosmetic appeal, occlusion, sound quality, physical comfort, security of fit, wind noise, acoustic feedback, telephone use, and perceived benefit in everyday listening. The HAAQ asks the patient to indicate their agreement with statements using a seven-point scale: Always True (99% of the time), Almost Always (87%), Generally (75%), Half-the-time (50%), Occasionally (25%), Seldom (12%), or Never (1%). This response scale was adapted from the Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit.7 Participants were asked to circle the descriptor that best represented their experience with the hearing aid fitting under evaluation. This questionnaire was completed at the end of each trial week.

Results

Speech Understanding in Noise. Figure 4 displays the mean speech understanding in noise results. A repeated measures ANOVA indicated no significant difference in HINT scores (F = 2.82, p = .08). On average, participants performed equally well with the three device fittings in the diffuse noise setting. Average performance differed by 1 dB or less across the three device styles.

Spatial benefit. The results of the spatial hearing test are shown in Figure 5. Spatial benefit was calculated by subtracting the SNR for the co-located speech and noise condition from the SNR obtained when speech and noise were spatially separated. On average, participants achieved a 2.5 dB SNR spatial benefit with the CIC fitting, 2.9 dB benefit with the RM, and 3.1 dB benefit with the BTE. A repeated measures ANOVA indicated no significant differences between the three device fittings for spatial benefit (F = 0.29, p = .74). All three device fittings allowed the listeners to take advantage of the interaural difference cues provided by spatial separation for improved functional SNR.

Figure 5. Mean HINT results for speech in co-located and spatially separated noise.

Hearing Aid Acceptance Questionnaire. Figure 6 displays results for the HAAQ items that included ratings of unaided hearing in addition to ratings of the three hearing aid styles. Longer bars indicate more perceived problems. It is evident from the first six items that the use of hearing aids in general resulted in significantly less difficulty in noisy situations, in quiet one-on-one listening situations, locating the source of a sound, hearing on the telephone, and greater overall satisfaction with hearing ability. Without hearing aids, participants were generally dissatisfied with their hearing ability. With hearing aids, they reported being only occasionally or seldom dissatisfied with their hearing ability.

The BTE was rated somewhat more favorably than the RM or CIC styles for hearing in noisy environments and in one-on-one quiet situations. Locating the source of a sound was seldom perceived to be difficult with any of the device styles. Talking on the telephone was occasionally a problem with the CIC, but seldom difficult with the RM or BTE.

Figure 6. Mean results for HAAQ comparing unaided ratings to the three hearing aid fittings for items related to performance and occlusion.

The last three items in Figure 6 are related to occlusion. Generally, the CIC created the most perceived occlusion, the RM somewhat less occlusion, and the BTE very little or no occlusion. With the BTE, ratings of these items were similar to ratings for unaided listening.

The HAAQ items that deal only with aided hearing are displayed in Figure 7. Feedback and wind noise were generally not a problem with any of the devices for the listeners in this study. The CIC and RM hearing aids were rated as being “always” or “almost always” comfortable. On average, the BTE was rated as somewhat less comfortable. Likewise, the CIC and RM devices were felt to be very secure (will not fall off), whereas the BTE was perceived as less secure. Regarding aesthetics, the CIC and RM were rated more highly for appearance than was the BTE. Interestingly, the RM was perceived to be as, or more, cosmetically appealing than the CIC. All devices were rated similarly, and quite highly, for quality of life improvement.

Preference rankings. At the conclusion of the three consecutive field trials, participants were asked to rank the three device styles in order of overall preference. A total of 5 participants chose the BTE, 4 preferred the RM, and 3 preferred the CIC style. This result was not different from chance (chi-square = .25, p = .88). Of the 8 participants whose top preference was the BTE or CIC style, 7 ranked the RM as their second most-preferred style. Only one participant ranked the RM as the least appealing of the three styles.

The preference results were analyzed to determine if there was an order effect, and results of the chi-square test revealed no significant effect of test order.

Figure 7. Mean results for HAAQ items comparing the three hearing aid fittings for items related to acoustic feedback, wind noise, comfort, security of fit, cosmetics, and quality of life improvement.

Conclusions

Results of the laboratory speech-in-noise testing revealed that, as a group, participants performed similarly with all three hearing aid styles when listening in diffuse, co-located, and spatially separated noises. Although not statistically significant, there was a slight trend toward better performance with the RM over the CIC of approximately .5 dB, and an additional .5 dB improvement with the BTE. Recall that the BTE had a directional microphone, which may account for this improvement in noise. It is also possible that the slightly better performance with the RM and BTE styles was in part due to the increased high frequency gain provided by these devices as compared to the CIC (see Figure 3).

Interestingly, all three devices provided similar spatial benefit, despite the less-than-optimal microphone location of the BTE device. The BTE fittings in this study utilized non-occluding dome tips. Results of a recent study suggest this type of open fitting may preserve low frequency spatial cues because it allows both amplified and unamplified sounds to reach the ear.8Subjectively, participants reported good benefit from all three hearing aid styles for listening in quiet, listening in noise, ability to localize the source of a sound, and improved quality of life. Participants rated the CIC and RM devices more highly for cosmetics and comfort relative to the BTE. The BTE and RM devices were rated more favorably for reduced occlusion, easier telephone use, and overall satisfaction with hearing ability, as compared to the CIC. On average, the BTE was rated slightly higher than the other two hearing aid styles for speech understanding in quiet and in noisy environments.

Perhaps the most noteworthy finding of this study is the participants’ final choice of device style. The most recent industry reports indicate that BTEs now account for over 70% of all hearing aid sales.9 Among the group of novice hearing aid users in this study, only 5 of the 12 participants (42%) chose a BTE over a custom product (CIC or RM) after having an opportunity to try each style of hearing aids for a week. It may be that for younger hearing aid users with active lifestyles, cosmetic concerns and security of fit issues are a higher priority when choosing a hearing aid style. This highlights the need for thorough exploration of patients’ pre-conceived concerns about amplification when selecting a hearing aid style, since these factors will likely have a significant impact on hearing aid success.

Undoubtedly, satisfaction with a first hearing aid fitting will influence acceptance of and success with hearing aids over a lifetime. The Remote Microphone device offers another alternative to help hearing health professionals provide the best fitting to meet each individual’s amplification needs.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by GN ReSound through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with the Clinical Investigation Regulatory Office, US Army Medical Department, Fort Sam Houston, Tex. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Departments of the Navy, the Army, the Department of Defense, the US Government, or GN ReSound.

CORRESPONDENCE can be addressed to HR or Dr Cord at:

References

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non-user adoption of hearing aids. Hear Jour. 2007;60(4):24-50.

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: The key influencing factors in hearing aid purchase intent. Hearing Review. 2012; 19(3):12-25.

- Orton JF, Preves DA. Localization ability as a function of hearing aid microphone placement. Hearing Instruments. 1979;30:18-21.

- Best V, Kalluri S, McLachlan S, Valentine S, Edwards B, Carlile S. A comparison of CIC and BTE hearing aids for three-dimensional localization of speech. Int J Audiol. 2010;49:723-32.

- GN ReSound. Advantage of microphone placement: a review of two external trials. Conducted on be by ReSound™. Available at: www.bebyresound.com/for-professionals/be-_milan_and_leuven_trials-_apr19_09.pdf

- Nilsson M, Soli S, Sullivan J. Development of the hearing in noise test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;95:1085-1099.

- Cox R, Gilmore C. Development of the Profile of Hearing Aid Performance (PHAP). J Speech Hear Res. 1990;33:343-357.

- Fortune T, Dittberner A, Gran F. Aided spatial hearing: electroacoustic and perceptual considerations. J Hear Sci. 2011;60(1):60-62.

- Hearing aid sales up 5.3% in first quarter. Hearing Review. 2012;19(5):10.

Citation for this article:

Block, KL and Cord, MT. Efficacy of the Remote-Microphone Hearing Aid for Novice Hearing Aid Users. Hearing Review. 2012;19(08):24-29.