An overview of the VA telehealth and pilot teleaudiology programs

The US Department of Veterans Affairs has been using telepractice for some time to monitor the health and well-being of thousands of patients nationwide —many of them older veterans living in areas far away from VA Medical Centers. The authors describe VA’s telehealth programs and pilot audiology programs in audiology telepractice.

Telepractice is not new to audiology and speech-language pathology practice in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). In the 1970s, Gwyneth Vaughn at the VA Medical Center in Birmingham, Ala, pioneered “tel-communicology” for the diagnosis and treatment of neurogenic communicative disorders.1,2 The technology was primitive, but these early pioneers of telepractice demonstrated the potential effectiveness of assessment and treatment using telehealth technology.

VA continued to evaluate telepractice in a study by Wertz and colleagues at the VA Medical Center in Martinez, Calif, that compared remote to face-to-face conditions in the appraisal and diagnosis of aphasia, apraxia, dysarthria, and dementia.3,4 VA continues to innovate in speech-language pathology practice and other areas of rehabilitation through telehealth.5-8

Traditionally, veterans seeking health care travel to the VA hospital or medical center. Approximately 60% of enrolled veterans reside in urban areas, while approximately 37% reside in rural areas. Fewer than 2% reside in highly rural areas. To alleviate long travel times and inconvenience for veterans and to provide care closer to their homes, VA established over 800 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOC). These clinics typically do not have all of the specialty services and staff found at the medical center. VA also recognized that a shortage of trained health care professionals and specialized facilities in rural areas meant that specialty health services were unavailable to the majority of the rural population.

To improve health care delivery, the Office of Telehealth Services (OTS) deployed an advanced array of health informatics, disease management, and telehealth technologies to target care and case management to improve access to care, and to improve the health outcomes. OTS was established in 2003 to support the development of new health care delivery models that use cutting-edge health information technologies to address the health care needs of veterans. OTS began deploying its clinic-based telehealth strategy in telemental health (2003), telerehabilitation (2005), teleretinal imaging (2005), and primary care telehealth (2011).

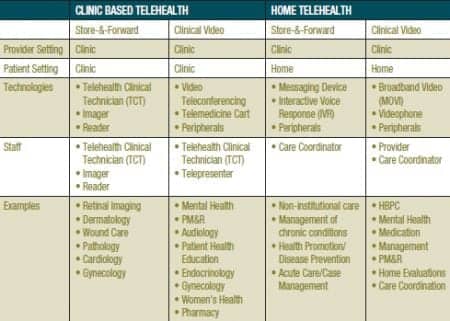

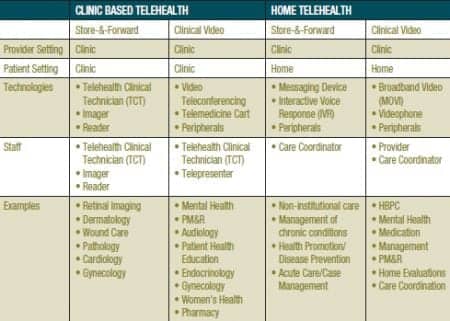

VA has evolved telepractice into three main areas:

- Clinical video telehealth (CVT). CVT uses real-time interactive videoconferencing—sometimes with supportive peripheral technologies—to assess, treat, and provide care to patients at a distant location. It can also provide video connectivity between a provider and a patient at home.

- Home telehealth (HT). HT monitors and manages patients through video into the patient’s home and use of mobile devices for acute and chronic disease management. The goal of HT is to improve clinical outcomes and access to care while reducing complications, hospitalizations, and clinic or emergency room visits for veterans in post-acute care settings and high-risk patients with chronic disease.

- Store and forward telehealth (SFT). SFT uses technologies to acquire and store clinical information (eg, data, image, sound, and video) that is then forwarded to or retrieved by a provider at another location for clinical evaluation or interpretation.

VA also operates telehealth networks in specialized programs such as Polytrauma System of Care and the Spinal Cord Injury/Disorder Program. The Polytrauma System of Care uses CVT to facilitate management of combat-wounded service members and to link five Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers with Polytrauma Network Sites and Polytrauma Support Clinic Teams, and military treatment facilities worldwide. The Spinal Cord Injury/Disorder Program uses CVT technology to link its 23 Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Centers and over 120 SCI spoke sites (Table 1).

Table 1. Examples of clinical video telehealth (CVT), store-and-forward telehealth (SFT), and home telehealth (HT) implementation in the VA’s Office of Telehealth Services (OTS).

OTS operates three national training centers, each specializing in an area of telepractice. The Rocky Mountain Telehealth Training Center provides training and support for clinical video telehealth services. Sunshine Telehealth Training Center provides training and support for home telehealth services, and the Boston Store-and-Forward Telehealth Training Center provides training and support for store-and-forward telehealth services.

Currently, VA is monitoring over 92,000 veterans in HT programs. VA manages over 87,000 veterans using CVT and over 118,000 veterans via SFT. Thus far in 2012, VA reported 597,278 telehealth encounters, 351,563 through CVT and 245,712 through SFT. In 2012, the top-five telehealth programs were teleretinal imaging to monitor diabetic eye disease, telemental health, Managing Obesity for Veterans Everywhere (MOVE), teledermatology, and telepsychiatry.

Telerehabilitation has grown rapidly in VA since it was formally established by OTS. In fiscal year 2008, rehabilitation services accounted for only 969 encounters. In 2012, that number increased dramatically to 12,438 encounters—almost all through CVT. In fiscal year 2008, audiology generated only 209 telehealth encounters. Thus far in 2012, audiology encounters have skyrocketed to 4,555 encounters.

Audiology Telepractice Initiatives

The remarkable growth in audiology telehealth did not occur by accident. It is not only a synergy of telehealth technology and remote-control software applications that has made audiology telepractice feasible, but it is also the result of careful planning and coordination. The audiology telepractice initiative is part of a multi-phase telehealth development project jointly managed by the Office of Telehealth Services, Office of Rehabilitation Services, and the Audiology and Speech Pathology National Program Office.

In 2011, VA established 10 pilot sites to investigate the feasibility of remote hearing aid programming and verification via telehealth, and to take audiology telepractice from proof of concept to an operational model for use in routine care delivery. The pilot program developed a concept of operations; identified a core team comprised of clinicians, technicians, information technology (IT) experts, and biomedical staff; evaluated remote software for effectiveness in audiology applications; and provided the pilot sites with telehealth equipment, compatible audiology peripherals and software, and support staff.

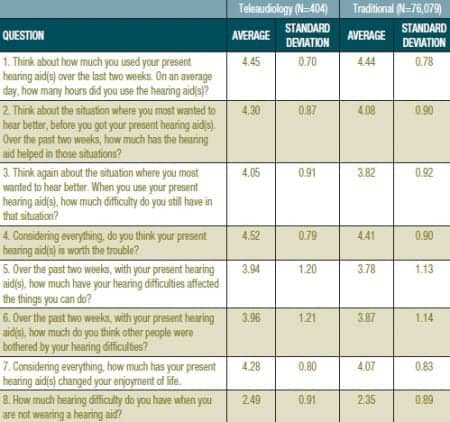

A key goal of the pilot project is collecting data on clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and estimated savings in travel costs. VA has configured its outcome data collection system to identify outcomes obtained through telehealth and traditional care delivery models. To date, VA has found no significant differences between outcome domains of the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids9,10 obtained though telepractice and those obtained through traditional face-to-face encounters (Table 2).

VA also included audiology in its VA Innovative Initiative (VAi2). This is a flagship program designed to tap the talent and expertise of individuals both inside and outside government to contribute new ideas that produce visionary solutions to advance VA’s ability to meet the challenges of becoming a 21st-century organization. Audiology telehealth solutions were included in the FY2011 VAi2 competition. VA Innovation Office is now working with the winning innovators to refine their proposals into well-defined projects with milestones, deliverables, and a pilot phase.

Table 2. Comparison of International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) results for tele-audiology (n=404) and traditional practice (n=76,079).

Challenges and Opportunities in Telepractice

VA recognized that widespread deployment of telepractice presented many challenges such as:n Telepractice requires an investment in equipment, information resources, and staff to work effectively.

- Since telepractice may be new to some areas of clinical practice, the lack of professional standards and the lack of data on efficacy and cost-effectiveness will need to be addressed.

- Services delivered by telepractice may not be reimbursed by insurance.

- Telepractice may not be covered by practice acts, or may be prohibited by some state professional regulations.

- State laws may restrict the delivery of clinical services across state lines.

- Providers may not be covered by malpractice liability when services are provided through a telehealth medium.

- Telepractice poses challenges in credentialing and privileging practitioners at different facilities.

- When services are provided through a network, between facilities, or over the Internet, patient confidentiality must be protected.

- There is a perception that telepractice is inefficient because it ties up a provider and technician.

Practitioner and Patient Acceptance. Practitioner and patient acceptance is a major hurdle, as it is for any major system change. To be accepted in routine practice, practitioners must be confident that telepractice will not be detrimental to the quality of service. They must feel that telepractice is appropriate for the type of services provided and the patients they treat. Practitioners must have confidence in the efficacy of telepractice through published studies.

Patients must also accept telepractice. They must feel that telepractice does not degrade the quality of the care they receive or interfere with the rapport and personal interaction they enjoy in face-to-face encounters with their health care practitioners.

Credentialing and Privileging. Credentialing and privileging of practitioners is a challenge, especially when services are provided between facilities and across state lines. When services are provided between two different medical centers, the originating (patient) site must have knowledge of the qualifications and other credentials, including licensure, required education, relevant training and experience, and current competence and health status of the telepractice provider at the distant (provider) site.

The process of credentialing and privileging reduces the risk to patients for adverse outcomes by completing the appropriate assessment of staff and reducing the risk for liability. When telepractice occurs between two facilities in the same organization, no special credentialing or privileging is needed. When telehealth services are provided between different medical centers, the process is more complicated because a formal agreement must be in place between the two facilities. This agreement defines that the facility accepting the telehealth services (the patient or originating site) has the necessary documentation on the practitioner and reports to the provider or distant site any quality of care concerns that are useful to assess the practitioner’s quality of care, treatment, and services for use in privileging and performance improvement.

Licensure can be a significant hurdle in private-sector settings when the practitioner must be licensed in the state where the service is provided. Some states do not allow telepractice across state lines, unless the provider is licensed in the state where the patient is physically located. Prior to delivering any services involving telepractice, the facility should consult with the professional regulatory agency in the state in which the practitioner is physically located, as well as the state where the patient is physically located.

Telehealth involves the use of technology and is therefore only a change in the manner in which existing clinical services are delivered. As such, there are no separate or distinct privileges for telepractice. When considering the granting of privileges at the facility where the practitioner is physically based (distant site), the general privileging process needs to include the appropriateness of telepractice. Any consideration concerning the appropriate utilization of telepractice by the practitioner needs to be considered as part of the privileging process by the facility where the practitioner is physically located.

VA uses two documents to define telepractice responsibilities:

- The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for Credentialing and Privileging for Telehealth is signed by facility leadership at each medical center participating in inter-facility telepractice activities. The MOU stipulates that all telehealth providers will be credentialed and privileged at the VHA facility from which they deliver telehealth services (distant site). Each participating facility will have an MOU with each of the other participating facilities.

- The Telehealth Service Agreement (TSA) is used for all clinic-based telehealth programs. The TSA delineates all of the variables and responsibilities for safe and effective telehealth service delivery and is modeled on The Joint Commission (TJC) hospital accreditation standards. The TSA includes a proxy privileging process for inter-facility telehealth providers, such as:

- Lists providers who are privileged at the provider facility to render inter-facility telehealth services for the specific telehealth application;

- Identifies if a telehealth service will be tele-consultation, telemedicine, or both;

- Specifies quality management and patient safety plans and variables, including provider performance indicators for the particular telehealth service; and

- Provides methodology and identifies variables for professional practice evaluations.

Space and Technology. Space and technology represent special challenges. Small outpatient clinics are often not designed for specialized clinical services, and rarely for space demands of an audiology clinic. Telehealth requires highly specialized technology, software, and information networks to function seamlessly. Telepractice also requires interdisciplinary collaboration and careful planning.

In some facilities, space can be dedicated and designed solely for audiology telepractice, but other situations may require sharing space and resources with other disciplines. Consideration must be given to the size and layout of the space, acoustics, lighting, and accessibility. Room design must be consistent with special requirements for tele-conferencing. Persons with expertise in telehealth room design can be helpful to identifying potential problem areas. In planning telepractice, it is important to assess T1 communication lines, adequate bandwidth for videoconferencing connectivity, competing technology during telehealth sessions, and the compatibility and characteristics of peripheral devices (eg, remote control software).

Privacy. While there are many telecommunications and software applications that might be used in telepractice, not all are secure. It is imperative that communication systems are secure and protect patient-identifying and privileged health information.

Medicare Restrictions. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has restrictions on telepractice. For example, CMS limits telepractice services to certain originating sites located in a rural health professional shortage area or in a county that is not included in a Metropolitan Statistical Area. Entities participating in a Federal telemedicine demonstration project may qualify as an eligible originating site regardless of geographic location.

Telepractice is limited to CVT. Asynchronous “store and forward” technology is permitted only in Federal telehealth demonstration programs conducted in Alaska or Hawaii. CMS limits coverage to consultations, outpatient office visits, psychotherapy, pharmacologic management, psychiatric interview, individual health and behavioral assessment, neurobehavioral status exams, end-stage renal disease services, nutrition therapy, and inpatient telehealth consultations and follow-ups by designated telehealth practitioners. Requests to add speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists were denied because they are not permitted under current law to furnish and receive payment for Medicare telehealth services (42 CFR 410.78).

Role of Technicians in Telehealth

The patient at the originating site (usually a community-based outpatient clinic) is always accompanied by a technician. Technicians can be trained telehealth technicians, registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, or trained telehealth clinical technicians (TCTs). Technicians are responsible for operating telehealth equipment, scheduling appointments for the day, assisting the audiologist with the evaluation or treatment, operating audiology equipment under the guidance of the audiologist, providing instructions or patient education, documenting workload data capture, and working with the facility telehealth coordinator to work out any process issues, equipment needs/problems, data collection, and any other logistical issues.

VA has evolved the use of two types of support personnel: audiology health technicians (audiology assistants) and telehealth clinical technicians trained in audiology services. Audiology health technicians have been trained in the use of telehealth technology. The advantage of health technicians (audiology assistants) is that they can perform all of the duties of an audiology assistant, as well as supporting telehealth encounters.

A telehealth clinical technician (TCT) is trained to support all types of telehealth and can support multiple clinical specialties at a single location. TCTs can be cross-trained in audiology to perform basic support services. The audiologist at the medical center (distant site) interacts with the patient at the community-based clinic (originating site), remotely controls all of the software from the medical center, and performs all of the services he/she would normally perform in a face-to-face encounter. The patient is accompanied by the telehealth clinical technician (TCT). The technician sets up equipment, connects the hearing aids, assists the audiologist, and provides patient instruction.

Clinical Protocols

Each facility must develop telehealth clinical protocols to ensure that the facility provides the right care at the right time and place while assuring patient safety and quality outcomes. Telepractice differs from traditional face-to-face encounters in many respects.

Providers must be constantly aware that they are interacting with patients over a different communication medium. Rather than being in the room with the patient, they are working over distance through a limited “bandwidth” that, to some degree, alters the patient-clinician interaction. Clinicians must take particular care to try to overcome these limitations.

It is crucial to begin each CVT visit with complete introductions for the patient and any caregivers or other support personnel present. All individuals involved on camera and off camera should be introduced. At times there may be personnel present who are not seen by the patient on the monitor. Nonetheless, these individuals should be identified to ensure the patient has awareness of their presence and participation. This is particularly important for support personnel and students who might “pop into” the patient’s view in support or educational roles. Without all individuals being identified at the outset, there is risk that the patient will feel confidentiality and privacy have been violated.

Summary

Telehealth and tele-audiology have many moving parts, including diverse team members, processes that enable implementation, infrastructure, training, and protocols for guiding practice. New models for tele-audiology practice are constantly evolving to meet the demand for hearing care that is high quality and accessible. Increasing the boundaries of traditional audiology practice that enables greater patient access requires renewed focus on issues of privacy and confidentiality. Despite the complexity of this practice, the benefits clearly outweigh the challenges. Tele-audiology is clearly moving hearing care in the right direction within the Department of Veterans Affairs and in health care settings throughout the United States and worldwide.

CORRESPONDENCE can be addressed to:

References

- Vaughn GR. Tel-communicology: Health care delivery system for persons with communicative disorders. ASHA. 1976;18:13-17.

- Vaughn G, Amster W, Bess J, et al. Efficacy of remote treatment of aphasia by Tel-Communicology. Rehabilitation R & D Progress Reports. 1987;25:432–433.

- Wertz RT, Dronkers NF, Berstein-Ellis E, Shubitowski Y, Elman R, Shenaut GK, Knight RT. Appraisal and diagnosis of neurogenic communication disorders in remote settings. Clinical Aphasiology. 1987;17:117-123.

- Wertz RT, Dronkers NF, Bernstein-Ellis E, et al. Potential of telephonic and television technology for appraising and diagnosing neurogenic communication disorders in remote settings. Aphasiology. 1992;6(2):195–202.

- Mashima PA, Birkmire-Peters DP, Holtel MR, Syms MJ. Telehealth applications in speech-language pathology. J Healthc Inf Manag. 1999;13(4):71–78.

- Mashima PA, Birkmire-Peters DP, Syms MJ, Holtel MR, Burgess LPA, Peters LJ. Telehealth: Voice therapy using telecommunications technology. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2003;12(4):432–439.

- Mashima PA, Doarn CR. Overview of telehealth activities in speech-language pathology. Telemed and e-Health. 2008;14(10):1101–1117.

- Tindall LR, Huebner RA, Stemple JC, Kleinert HL. Videophone-delivered voice therapy: A comparative analysis of outcomes to traditional delivery for adults with Parkinson’s disease. Telemed and e-Health. 2008;14(10):1070–1077.

- Cox RM, Alexander GC. The International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA): Psychometric properties of the English version. Int J Audiol. 2002;41:30-35.

- Cox RM, Alexander GC, Beyer CM. Norms for the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14:403-412.

ALSO IN THIS SPECIAL ISSUE (OCTOBER 2012) ON TELEAUDIOLOGY:

- Extending Hearing Healthcare: Tele-audiology, by Jerry Northern, PhD

- The Need for Tele-audiometry, by De Wet Swanepoel, PhD

- Are You Ready for Remote Hearing Aid Programming? By Jason Galster, PhD, and Harvey Abrams, PhD

- Infant Diagnostic Evaluations Using Tele-audiology, by Deborah Hayes, PhD

- Online Global Education and Training, by Richard E. Gans, PhD

- Therapeutic Patient Education via Tele-audiology: Brazilian Experiences, Deborah Viviane Ferrari, PhD

- Telepractice in the Department of Veterans Affairs, by Kyle C. Dennis, PhD, Chad F. Gladden, AuD, and Colleen M. Noe, PhD

Citation for this article:

Dennis KC, Gladden CF and Noe CM. Telepractice in the Department of Veterans Affairs Hearing Review. 2012;19(10):44-50.