Business Development | August 2020 Hearing Review

By Robert M. Traynor, EdD, MBA

“The meeting of two personalities is like contact of two chemical substances: If there is a reaction, both are transformed,” said Carl Jung. Here is a look at how various personality styles and preferences—of both patients and clinicians—can be appreciated and accounted for through proven methods during the hearing rehabilitiative process.

While some parts of the country are likely better off than others, Shafer1 presents up-to-date virus statistical predictions and reported data on the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States, as well as other parts of the world. At this writing, the data indicates the United States is on the downside of the infection curve, suggesting—with some fits and starts—states are on their way to whatever will soon become the “new normal.”

Certainly through the second quarter and through 2020, hearing care clinicians across the United States have and will continue to demonstrate their value by differentiating their clinics from the “sales operations,” providing valuable assistance to their patients—despite the profound practice adjustments required by the Covid-19 pandemic. While big box stores, manufacturer clinics, and others closed, numerous independent practices served their patients with creativity, expertise, technology, and innovative management. They followed their patients through the pandemic with innovation, such as telehealth and drive-up services.2 They and their employees were on the front lines, keeping patients hearing throughout their long days at home.

Now it is time to think about how to practice in the post-Covid-19 period. In search for hearing care services, consumers seek professionals who not only offer the latest diagnostic procedures and technology, but who will also work to establish a dependable interactive relationship. Therefore, it is important to consider the basics of clinician-patient relationships by reviewing how patients interact with the world. An examination of these parameters of personal interactions allows audiologists and dispensers alike to refine their patient interactive skills by understanding why patients respond as they do in certain situations.

The 3 Keys to Patient Relationships

Trust. Kasparian3 indicates there are two fundamental ingredients to building patient trust: 1) Patients must believe that the clinician’s intent is to do them no harm and to ethically act in their best interests, and 2) They need to believe the clinician has the capability and competence to accomplish these goals.

Trust is a basic need for a successful patient partnership. The relationship must be collaborative, loyal, and solid for both parties. If the partnership needs support or guidance, the partners in the relationship (the clinician and the patient, as well as at times the patient’s significant other) trust they can come together in a way in which the patient’s needs and concerns are resolved. During the Covid-19 pandemic, clinicians who were creative and maintained their practice with telehealth and set up drive-through support, built an enduring trust with patients that should last for years.4

Listen. The art of listening has long been part of hearing care counseling,5-8 as well as good salespersonship. Genuine listening builds relationships, solves problems, ensures understanding, resolves conflicts, and improves accuracy and efficiency with less wasted clinic time. Listening is both a complex process and a learned skill. It requires a conscious intellectual and emotional effort. Without intensive listening, clinicians will miss essential information pertaining to their patient’s generation, personal style, lifestyle, communication needs, and other factors fundamental to their aural rehabilitative process.

While there is a need for clinicians to talk during clinical sessions for necessary counseling, their talking is best kept at a minimum. Counselors and sales professionals alike suggest that 60% listening and 40% talking is a good place to begin, and that percentage can change as the relationship evolves between the patient and clinician.

Communicate. In addition to trust and listening, hearing-impaired consumers do business with people they like. In the early stages of the clinician-patient relationship, effective communication ensures that a practice meets a consumer’s needs. As time goes on, regular contact with the patient allows the relationship to grow, offering security that the clinician is still involved with and integral in their care. There is no time like the Covid-19 pandemic to have solidified that communication. Clinicians who responded by calling patients, conducted telehealth, Facetime, offered curb-service, and other innovations will be perceived as those who cared during the toughest of times. Now that the treatment partnership is firmly established, the relationship requires continued attention to ensure that it does not deteriorate. Understanding the personal style of the patient, as well as that of the clinician—and the interaction of the two—will greatly support relationship maintenance.

Personal Style in Hearing Care

Trust, listening, and communication do not happen without significant changes in how practitioners relate to their patients, and this is especially with the Baby Boomers. Citron9 indicates that the most-common mistake practitioners make is envisioning their task as just supplying information—cold hard facts and descriptions. While these authoritarian methods, based upon the medical model, worked well in the past, our newest generation of patients do not respond well to this technique. They expect (and should receive) a fine-tuned individualized rehabilitative process, as well as a treatment plan that allows for participation in their care with the clinician and staff.

Peer-reviewed questionnaires of hearing handicap (eg, COSI, HHIE, etc) are greatly beneficial and should be used in this process. However, one drawback these questionnaires have is that they categorize all the patients’ personality as essentially being the same.

Personality testing and assessment refer to techniques that are used to accurately and consistently measure personality. Psychologists use these tests to guide therapeutic interventions, and to help predict how patients might respond in various situations. Like psychologists, hearing care professionals can use these methods to facilitate trust, listening, and communication that greatly enhance the rehabilitative treatment process. Knowledge of personal style unlocks the special patient differences that explain the multitude of reactions to hearing loss, tinnitus, and the devices used to reduce or alleviate the hearing-related problem.

About 35 years ago, Staab10 observed that many different types and degrees of personalities offered themselves for rehabilitative treatment. He felt that if one could determine, according to patient personality type, how patients would cope, react, and interact with their hearing impairment and hearing aid fitting, clinicians could better respond to their specific needs. A few years later, Traynor and Buckles11 also recognized that knowing a patient’s personality type, by means of a personality assessment, might lend valuable information and insight into patient rehabilitative needs. At the time, they suggested the consideration of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)12 and its resulting 16 different personal styles to facilitate better, more fine-tuned, aural rehabilitative treatment. Bayne13 points out that the daughter-mother team of Katherine Briggs and Isabel Myers did much to clarify and fine tune the theories of famed Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, developing a tool that is now commonly used to explain people’s personalities and the different ways they prefer to use their perception and judgment.

While these early observations and suggestions were sheer speculation at the time, savvy new-century practices in all disciplines (ie, medicine, dentistry, chiropractic, optometry, etc) use personal style to fine tune their treatment techniques. In routine clinical practice, however, the observation of 16 personal styles of the MBTI has been found to be cumbersome.14

Rationale for the Use of 4 MBTI Personal Styles

While it is difficult to observe the 16 different MBTI personal styles, Traynor and Holmes15 found it much easier to clinically identify four general personal style—or “temperment”—classifications as described by Keirsey: Guardian, Idealist, Artisan, and Rational.16,17 This simplifies the structuring of patient treatment according to personal style. While there are several personal style assessments designed to determine four general personal styles (eg, DISC, Tracom, Colors), Keirsey offers the most research support for use with hearing-impaired patients.

The MBTI has four preference continua:

- Extroversion <—> Introversion

- Sensing (S) <—> Intuitive (N)

- Thinking (T) <—> Feeling (F)

- Judging (J) <—> Perceiving (P)

The characteristics of Extroversion and Introversion are generally well known and easy to identify even by the casual observer, and therefore are excluded from the latest Keirsey system. Bayne13 reports that David Keirsey believed the Sensing (detail oriented)-Intuitive (not detail oriented) continuum were significantly influenced by the Judging (rigid/scheduled)-Perceiving (flexible/unscheduled) preferences. Thus, if a person is detail-oriented (S), they tend to be most influenced by either being rigid and scheduled (J) or flexible and unscheduled (P). This results in either the Sensing-Judging (SJ) classification called the Guardian or the Sensing-Perceiving (SP) Artisan personality type. Similarly, Keirsey believed that the Thinking (objectivity)-Feeling (personal values) continuum had the most effect on Intuitive (non-detail-oriented) type. This results in either the Intuitive-Thinking (objectivity) called the Rational (NT) or the Intuitive–Feeling Idealist (NF) personality type.

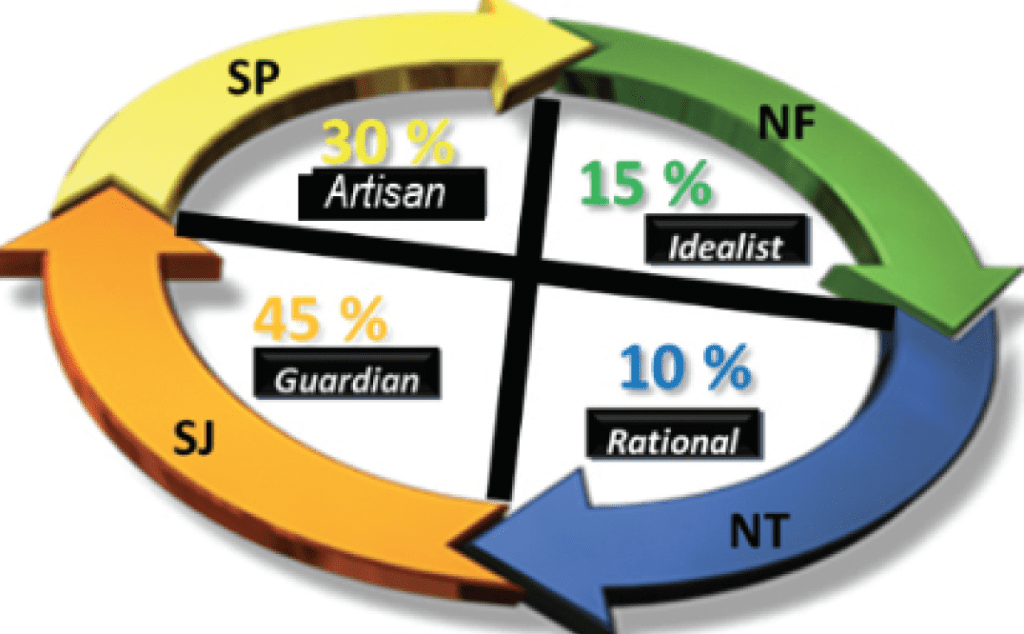

In this way, Keirsey18 provides four easily identifiable personal styles. Figure 1 presents results from the most recent study of the incidence of these personal styles encountered in the general population:

1) Guardian (SJ). The Guardian is dutiful, cautious, humble, and focused on credentials and traditions of being dependable. They are helpful and hard-working loyal mates and responsible parents. The Guardian is also practical and believes in following the rules and cooperating with others, as well as valuing and appreciating authority—but with high expectations. These individuals also have an intense need to maintain control of situations.

2) Artisan (SP). The Artisan has a constant need for pleasure and stimulation. They are fun-loving, optimistic, realistic, and focused on being unconventional. They are bold and spontaneously playful mates, creative parents, and troubleshooting leaders. Artisans trust their impulses, want to make a splash, seek stimulation, freedom, and dream of mastering action skills. Artisans have a natural ability to excel in the arts.

3) Idealist (NF). Idealists are highly ethical in their actions and hold themselves to a strict standard of personal integrity; they are always on a quest for self-knowledge and self-improvement. Idealists are naturally drawn to working with people. Whether in education or counseling, they are giving souls who are trusting, spiritual, yet focused on personal journeys and human potentials. They have an intense need for harmony in their lives, are loving, kindhearted, and trust in their intuition and dream of attaining wisdom.

4) Rational (NT). Whatever systems and/or technology spawns their curiosity, the Rational personality type is the problem solver who will analyze things until they understand how it works—so they can figure out how to make it work better. They tend to be pragmatic, skeptical, self-contained, and focused on systems analysis. They pride themselves on being ingenious, independent, and strong willed.

These incidence figures in the general population have changed to some degree over the years, but their significance remains the same and are like the hearing-impaired population. After some experience, it is efficient use of clinical time to forego conducting formal assessments as it is possible to derive a patient’s personal style by interview and observation.

Detecting Personal Style without a Test

During the interview, history, cerumen removal, audiologic assessment, and other procedures, clinicians who have studied and practiced type interpretation can identify a patient’s personal style. By conducting “small-talk” during routine procedures and follow-up visits, you can obtain a rough estimate of the patient’s personality and correctly classify their Keirsian personality type most of the time. This allows for rehabilitative interactions focused toward how the patients best react and interact within their environment. Bayne13 and Traynor and colleagues15,19 have suggested several methods to informally estimate patient personality type, indicating that experienced clinicians often do this subconsciously when comparing their current patient to those seen in the past, then adjusting treatment programs accordingly. They describe seven basic principles of informal clinical assessment of personal style. These principles include:

1) Look for evidence of a personality trait or pattern.

2) Look for evidence against that observed trait or pattern.

3)Look for the possible effects of the situation on the trait or pattern that has been observed.

4)Look for the ambiguity of behaviors and similar behaviors that are evidence of more than one behavioral preference.

5)Discover your stereotypes and favorite terms or personal styles and try to allow for them.

6) Compare your observations with those of others.

7) Study personality type theories.

In the beginning, it can be a bit difficult to identify a patient personality type, but with practice it gets easier. The use of these techniques allow special interactions and relationships to develop between patient and clinician.

Clinicians Must Also Account for Their Own Personal Styles

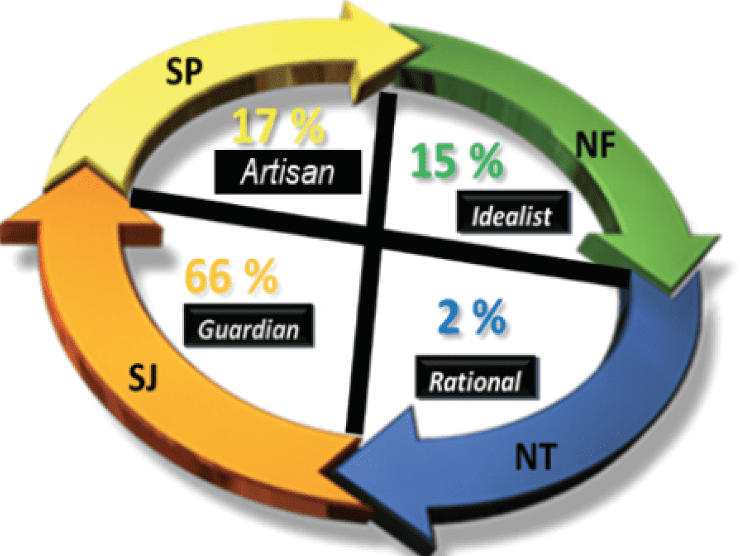

The personal style of the clinician may also make a substantial difference in successful patient interactions. Figure 2 presents the latest study of clinician personal style by Pinsky et al.20 Clinician personal style may explain why certain patients do better with some clinicians than with others, or why some clinicians become frustrated with certain types of patients. Since their role is to provide the best possible hearing care, hearing care professionals must learn to work with all personal styles and ignore their own natural tendencies that may affect the outcome of the rehabilitative process. If you are a clinician of a particular personality type, here are some major tendencies that must be overcome in the patient treatment process:

Guardian (SJ) Clinicians (66% of Audiologists):

- Do not expect every patient to be on time.

- All patients do not want an organized step-by-step program.

- Do not be practical for everyone, especially Rational (NT) patients.

- Do not focus on the procedure, especially for Artisans and Idealists.

- Do give clear objectives and prepare for situations.

- Have options when a treatment program/hearing aid does not work.

Artisan (SP) Clinicians (17% of Audiologists)

- Do put up with long procedures when they are necessary.

- Try to focus more on the overall outcome rather than the process.

- Accuracy of a particular adjustment or procedure may be more important than you think.

- Be tolerant of patient difficulties.

Idealist (NF) Clinicians (15% of Audiologists)

- Be aware that you will never make all of your patients happy.

- Good clinicians need to disagree with their patients sometimes.

- Focus and concentrate on boring rehabilitative treatment tasks.

- Do not expect everyone to care as much as you do.

Rational (NT) Clinicians (2% of Audiologists)

- Perfection is not always necessary.

- Most patients need to have things simplified.

- Most patients do not require long presentations including the background for each procedure.

This is simply the beginning of how we can make a major difference in the relationships that we create with our patients. In this rapidly approaching post Covid-19 period when all patients will gradually return for face-to-face interactions in the clinic, the exercise of identifying a patient’s personal style and applying that information into the treatment process will certainly enhance the patient-clinician relationship that has already been established.

References

1. Shafer, S. (2020. Steve’s COVID Analysis, 2020-04-29. Stanford University, Retrieved April 30, 2020.

2. Strom KE. Results of the Covid-19 Impact Survey #3 (May 13-22) for hearing healthcare practices. Published June 10, 2020.

3. Kasparian S. Ball Systems Blog. The importance of strong customer and business partner relationships. https://www.ballsystems.com/blog/the-importance-of-strong-customer-and-business-partner-relationships. Published June 4, 2018.

4. American Academy of Audiology (AAA). CMS expands list of Medicare eligible telehealth providers to include audiologists. https://www.audiology.org/advocacy/cms-expands-list-medicare-eligible-telehealth-providers-include-audiologists. Published May 1, 2020.

5. Clark JG. Chapter 20: Supporting practice success. In: Glaser RG, Traynor RM, eds. Strategic practice management. 3rd ed. Plural Publishing; 2018.

6. Clark JG, English KM. Counseling-infused audiologic care.1st ed. Pearson; 2013.

7. Luterman DM. Counseling persons with communication disorders and their families. 6th ed. Pro Ed; 2016.

8. Crandell C. Personal Communication Counseling Course. University of Florida Doctor of Audiology Program. University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla; 1995.

9. Citron, D. Motivational interviewing in audiology: How to become an appreciative ally. Hearing Journal. 2020;73(1):32-33.

10. Staab W. Types of hearing-impaired patients. Oral presentation at: Jackson Hole Rendezvous; 1985; Jackson Hole, WY.

11. Traynor RM, Buckles KM. Personality typing: Audiology’s new crystal ball. In: Kochkin S, ed. High performance hearing solutions. Hearing Review(monograph).1997.

12. Briggs KC, Myers, IB, McCaulley MH. Myers-Briggs type indicator. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1976.

13. Bayne R. The Myers-Briggs type indicator: A critical review and practical guide. New ed edition. Nelson Thornes Ltd; 1995.

14. Traynor RM, Buckles KM. Personal style: A pilot study. Oral presentation at: Annual Convention of the American Academy of Audiology (AAA); 1997; Ft Lauderdale, FL.

15. Traynor RM, Holmes AE. Personal style and hearing aid fitting. Trends in Amplification.2002;6(1): 1-31.

16. Keirsey D, Bates M. Please understand me: Character and temperament types. 5th ed. Prometheus Nemesis Book Company; 1984.

17. Keirsey D. Please understand me II: Temperament, character, intelligence. 1st ed. Prometheus Nemesis Book Company; 1998.

18. Keirsey website. The Four Temperaments. https://keirsey.com/temperament-overview/. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

19. Traynor R. Chapter 3: Relating to patients. In: Sweetow R, ed. Counseling for hearing aids.1st ed. Cengage Learning; 1999.

20. Pinsky E, Holmes A, Traynor R, Huart S. Keirsey personal style among audiology clinicians. 2005. Unpublished.

Correspondence can be addressed to Dr Traynor at: [email protected].

Citation for this article: Traynor R. Competing in the new era of hearing healthcare. Part 4: Differentiating your practice by relationships in the Covid-19 era and beyond. Hearing Review. 2020;27(8):18-22.