| To realize the full capabilities of hearing instruments, people with hearing loss need, and can benefit from, a more comprehensive type of aural rehabilitation program that involves peers exchanging information. A hearing aid by itself is often not enough. An examination of the literature supporting aural rehab groups, as well as a look at the deep-seated needs of hard-of-hearing individuals, is offered relative to counseling. |

Without question, there have been marvelous strides in hearing instrument technology in recent years. There is little debate that these impressive advances can and do offer improved listening advantages to hard-of-hearing people. As we’ve also learned during this time, these advances are being accompanied by an increased sensitivity on the part of the professional community to the psychosocial consequences of a hearing loss. We have more and more evidence that conclusively demonstrates the positive impact that personal amplification can have on a person’s adjustment and quality of life.1,2 But, as Kochkin & Rogin1 pointed out in their January 2000 HR article, these studies simply "quantify the obvious." Of course hearing instruments help; this should be no surprise to any of us. Still, all of this accumulating evidence and focus on quality of life are positive trends, ones that we can hope will continue to engage professionals into the new millennium.

However, even as we acknowledge these positive trends, they do not fully respond to the total impact that a hearing loss can have upon the life and well-being of the affected individual and his/her family. Too often hearing instruments are presented—or understood—as panaceas, as devices that can “restore” a person’s hearing capacities comparable to that enjoyed by a person with normal hearing. What this approach implies is that the provision of hearing instruments alone are a sufficient response to the full consequences of a hearing loss in the life of an individual. That is, since hearing is "restored" by hearing instruments, no further efforts are required.

On the contrary, it is necessary that we stress that hearing instruments are just one component, albeit arguably the most important one, of what should be construed as a rehabilitative process, one that includes, or should include, other components as well. I certainly do not mean to minimize the value of hearing aids. As someone who has worn aids for nearly 50 years, I can personally testify to their value and absolute necessity. I shudder to think what my life would be like without them. But it’s important for all of us to recognize that hearing aids alone do not, and cannot, address all the difficulties that are experienced by someone with a hearing loss.

There is abundant evidence to support the contention that it’s possible to further reduce the handicapping effects of a hearing impairment beyond that occurring with the provision of hearing aids by themselves. This can be done by ensuring that hearing-impaired people are provided with the full range of rehabilitative services, as well as hearing assistance technologies other than hearing aids.

Let’s consider the typical prospective hearing instrument user. Many people have either been dragged or nagged into hearing centers, or have experienced such evident hearing difficulties that they feel that they have no choice but to succumb and “get a hearing aid.”

Hearing care professionals know that, on average, people with adult-onset hearing loss have been experiencing hearing-related communication problems for about seven years before they seek help. Think about those years. Think about the effects these hearing problems may have had upon the person’s family, social circle and employment situation. Consider the psychosocial problems, the stress, anxieties and conflicts associated with frequent, erratic and misunderstood communication breakdowns. Most prospective hearing instrument users must have experienced such problems or they wouldn’t be seeking help (or others wouldn’t be seeking help for them!). We trivialize the sense of hearing and the role that audition plays in our lives if we believe that hearing instruments alone can enable people to resolve the problems wrought by years of poor hearing and an unacknowledged or untreated hearing loss.

No matter how advanced and well-fit the hearing instruments, they cannot retroactively help people understand how the hearing impairment has affected their current behaviors and relationships. Wearing the aids will not immediately overcome the maladaptive habits formed in these years. We cannot effectively “treat” the person with the hearing loss separate from the very real fact that it’s the entire family that has the “hearing problem.” By focusing on the hearing instrument as the sole “prescription” for the hearing impairment, we are overlooking the total impact of a hearing loss upon the life of the affected person.

What I am suggesting is that the hearing aid fitting procedure be defined in a way that it routinely incorporates a group hearing aid orientation program as an integral part of the entire process. I’ve made this point before3,4 but it is worth re-stressing here. Rather than focus on just the selection and follow-up of the hearing instrument itself, the process would incorporate information, group interactions, communication strategies, and evaluation and selection of the full range of hearing assistance technologies.

Twenty Years of Research

The provision of a group post-fitting program is not an original suggestion (see Abrahamson5 for extended references). It has been recommended and offered often, at various times in different places. I don’t know precisely what sort of programs are offered in other countries, but I do know that, currently in the United States, in spite of the many references on the desirability of such programs, in actuality relatively few are offered or take place.

It’s not as if there are serious questions regarding the effectiveness of group aural rehabilitation programs. I would venture that most professionals accept their value, though not necessarily their being coupled to the hearing instrument fitting process. Mainly, it appears that group follow-up programs are not now being provided because:

1) Dispensing professionals do not feel that they can be incorporated in their practice in an economical manner, and

2) Even when they are offered, many (if not most) new hearing instrument users fail to take advantage of the opportunity.

Both of these assertions, in my opinion, are rather simplistic. The overall research on the success of group aural rehabilitation programs is fairly unambiguous. While the details of the programs vary somewhat in the numerous research studies, there is convincing evidence that those people who receive enriched counseling services show a greater reduction in the hearing handicap than those who receive less such services.

Twenty years ago, Brooks6 examined the extent of handicap reduction and hearing instrument usage in two groups of patients, one which received extensive counseling and one which did not. His conclusions:

"Although the provision of a hearing aid alone produces some reduction in the handicap, a much greater reduction appears to be achieved by providing some measure of counseling to the hearing-impaired subjects."6

Also, about 20 years ago, a study conducted by Surr, Schuchman & Montgomery7 compared hearing instrument usage in patients receiving a two-week residential program at Walter Reed Hospital to a group that received a traditional two-hour follow-up program. Their conclusions were similar to those reported by Brooks. (Author’s Note: When I received my hearing aids at Walter Reed Hospital nearly 50 years ago, it was coupled to a two-month residential aural rehabilitation program! And I can personally testify how effective it was.)

Ten years later, Smaldino & Smaldino8 essentially reached the same conclusion. All four of their experimental groups who received hearing instruments displayed demonstrable help from the aids—as I’ve already noted, of course, hearing aids by themselves do help—but they also found that the handicap of hearing loss was further reduced by the group receiving a month-long aural rehabilitation program.

In the 1992 study by Abrams et al.9 it was found again that, while the conventional method of fitting hearing instruments does indeed reduce the handicap of a hearing loss, the handicap can be further reduced when the selection process includes a short term aural rehabilitation program.

The positive impact of additional time spent on counseling the prospective hearing instrument user was more recently corroborated by Kochkin10 when he reported survey results that showed patient satisfaction increasing as counseling time increased. Considering also his findings that over 16% of people receiving hearing instruments have completely rejected them, and that only 60% of hearing instrument recipients are satisfied with their aids, quite evidently there are shortcomings in the current model of hearing instrument dispensing that need to be addressed.11

What about the argument that clients do not desire such programs or take advantage of them when offered? While true for some people, this argument has been overextended. For example, in a 1997 survey conducted by the American Academy of Audiology, it was found that almost half the people desired more information about other rehabilitation options. Moreover, this figure probably underestimates the situation, since it is unlikely that the majority of new hearing instrument users are aware of the full range of available services that can be helpful to them. Generally, during the first stage of hearing instrument use, people don’t even know enough to ask the right questions. They don’t know, for example, about the existence of hearing assistance devices other than hearing instruments, or how to effectively use communication and repair strategies. And, if this type of information is not communicated during the hearing aid selection process, it’s unlikely that it will ever be known. It’s at this time when people have acknowledged that they need hearing assistance and when they are being advised by a professional who has the information that they require. This is the time when they will be most receptive to learning about other ways to reduce the problems caused by a hearing loss.

In today’s world of financial constraints and rising health care costs, the budgetary argument would appear to be particularly salient. If an aural rehabilitation program is joined to the hearing aid selection procedure, then superficially it does appear that costs will increase. This is not inevitable, however. Several studies have shown that people who receive an expanded educational/counseling program return their aids much less frequently than those who have not received such a program.12,13,14 This certainly would reduce costs for the hearing care professional.

We should not be surprised at this finding, nor the likelihood that the need for individual follow-ups will diminish when people are enrolled in a group program. Professionals in private practice will find that the group setting enhances patient satisfaction, which translates into more “word-of-mouth” referrals—probably the best source of new patient contacts available. When conducting such programs, I’ve often found that many monaural hearing instrument users decide to accept binaural amplification, not necessarily because of anything I say, but because other members of the group come out strongly in favor of binaural amplification. And, finally, in an organized group follow-up program, there is time to evaluate, select and demonstrate other types of hearing assistance technologies. All of these factors have potentially positive economic consequences for the hearing care professional.

Becoming Consumer-Oriented: Meeting Needs

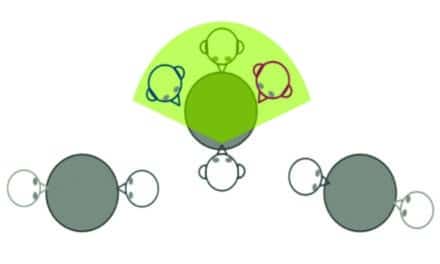

In any discussion on hearing care, it makes sense to review some of the deep-seated needs that hard-of-hearing people possess. Many of these requirements can be best fulfilled by the hearing care professional in a group setting. True, many of the needs enumerated below can be met in individual sessions, but some cannot—and all need reinforcement and repetition.

- Hard-of-hearing consumers need general information about the causes and treatment of hearing loss. People can deal with a problem much more effectively when they have greater understanding of the nature of the problem. Many people come to clinics wanting to be “fixed” with a medical or surgical procedure; they have to understand why some types of hearing losses cannot be “fixed” medically, and that the best “treatment” is often a well-functioning hearing instrument.

- They need information about the listening implications of their own hearing loss, explained in a way that they can understand (for example, why people seem to be “mumbling,” or why they can “hear” speech but not understand what is being spoken).

- A person’s spouse or adult children should also understand the communicative implications of their loved one’s hearing loss. One technique I often use in a group setting is to play filtered speech to these people. Often their responses are amazement and mortification: “Is that what she has been hearing! I never knew!” This simple step can decrease tensions and stress within the family.

- They need an opportunity to review and share their listening experiences with the clinician and other group members. We’ve all seen examples of how reluctant users experiencing problems with their first hearing instruments want to discard the aids as “being too much trouble.” The best way to encourage these people to continue their hearing instrument trial period and to work through their problems is for them to share their experiences with members of the group, many of whom have experienced similar problems and overcome them.

- The group setting lends itself to help people develop realistic expectations of what a hearing instrument can and cannot do for them. Some people’s expectations may be unrealistically high, while others set their standards too low. A group follow-up program, that takes their individual hearing losses into account, can help them calibrate their expectations to a realistic and appropriate level.

- People need information on how to troubleshoot their hearing instruments, how to take care of their earmolds, and how and when to change batteries. They need to know why one type of hearing instrument was selected rather than another. Certainly all of this information is ordinarily conveyed in the usual delivery model. However, from the perspective of the user, so much is happening during the fitting session that much of what they are told is forgotten when they leave the room. It takes time and repetition for people to absorb new information. This, indeed, may be one of the key advantages of an organized follow-up program: it provides the time for important information and experiences to be conveyed and assimilated.

- If we accept the notion that our focus is on the needs of the individual, and not on hearing instruments per se, then people require information about other kinds of hearing assistance technologies. Several personal examples illustrate what I mean. A hearing aid will not help wake me up when I’m sleeping. For that I need a vibratory or light signal. To ensure that I can understand on the telephone, I find an in-line amplifier very helpful. Sometimes I use one that permits me to employ a neck loop so that I can listen with both ears. Other people with different degrees of hearing loss need other kinds of telephone assistance, of which there are innumerable possibilities.

There are many devices that can be useful for some people in particular circumstances, such as TV listening devices, conference microphones, personal FM systems, doorbell and telephone signal lights, visual smoke alarms and large-area listening systems.15 These devices not only impact one’s quality of life, but can have major vocational implications in cases where a person’s job or future is jeopardized by a hearing loss. - Most people with hearing loss can benefit from information about various kinds of communication repair strategies that can be used to enhance interpersonal communication. The basic principles of speech reading are important for people with hearing loss to know about. With a little practice and focus on the lips, it’s possible to increase a hearing-impaired person’s communication competencies. By learning to be more “assertive” in their communication practices, hard-of-hearing people can be more effective communicators—but they have to know what to do and when to do it.

- Even after receiving the kinds of services outlined above, many people with hearing loss still need the continuing support of other people who have, or are going through, similar circumstances. The wise practitioner will keep an open channel to a local chapter of Self-Help for Hard of Hearing People (SHHH) and refer his/her clients to this consumer support group.

Conclusion

Outlined above are only some of the major, general needs of hard-of-hearing people. It takes time to deal with the communicative as well as the psychosocial implications of a hearing loss; it takes time to evaluate the need for, and to provide, other types of hearing assistance technologies; it takes time to help patients and family members understand the implications of a partial hearing loss; and it takes time, particularly for some older people, to work through the fitting procedures until they reach the point that they are content with, and are receiving, the full benefits of hearing instrument amplification. The key element here is time: time which would be available if the hearing aid selection procedure were to be defined in a way that includes the routine inclusion of a group post hearing aid fitting program.

Of course hearing instruments are marvelous and, for many of us, indispensable devices. They make it possible for us to more fully participate in the social, cultural and economic activities of our societies. Without them, the lives of millions of people worldwide would be very different—and certainly more constricted and limited. But to realize their full value, and to go beyond what these devices can offer, people with hearing loss need, and can benefit from, a more comprehensive type of aural rehabilitation program.

In brief, a hearing aid by itself is often not enough. As a profession moving into the 21st century, we should set our sights on the rehabilitative process that people with hearing loss require, rather than the specific product we are dispensing.

Acknowledgements

This article was adapted from a paper delivered at the “World of Hearing” conference, co-sponsored by the European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Assn. (EHIMA) and the International Federation of Hard of Hearing People, Brussels, Belgium, May 29, 1999. The paper was supported by Grant #H133E9800010 from the US Department of Education, NIDRR, to the Lexington Center.

References

1. Kochkin S & Rogin C: Quantifying the obvious: The impact of hearing instruments on quality of life. Hearing Review 2000; 7 (1): 6-35.

2. Hampton D: Mulrow et al…revisited. Hearing Review 2000; 7 (1): 44-45.

3. Ross M: A retrospective look at the future of aural rehabilitation. Jour Acad of Rehab Audiol 1997; 30: 11-28.

4. Ross M: Redefining the hearing aid selection process. Aural Rehabilitation and its Instrumentation, Special Interest Division #7. Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language Hearing Assn 1999; 7 (1): 3-7.

5. Abrahamson J: Patient education & peer interaction facilitate hearing aid adjustment. In S Kochkin & KE Strom’s (eds) High Performance Hearing Solutions, V1. Suppl. to Hearing Review 1997; 4 (1): 19-22.

6. Brooks DN: Hearing aid use and the effects of counseling. Austral J of Audiol 1979; 1 (1): 1-6.

7. Surr RK, Schuchman GI & Montgomery AA: Factors influencing use of hearing aids. Arch Otolaryngol 1978; 104: 732-736.

8. Smaldino SE & Smaldino JJ: The influence of aural rehabilitation and cognitive style discourse on the perception of hearing handicap. Jour Amer Acad Rehab Audiol 1988; 21: 57-64.

9. Abrams HB, Hnath-Chisolm T, Guerreiro SM & Ritterman SI: The effects of intervention strategy on self-perception of hearing handicap. Ear Hear 1992; 13 (5): 371-377.

10. Kochkin S: Paper delivered at the World of Hearing Conference, Brussels, Belgium, May 29, l999.

11. Kochkin S: MarkeTrak V: "Why my hearing aids are in the drawer": The consumer perspective. Hear Jour 2000; 53 (2): 34-42.

12. DiSarno N: Informing the older consumer—a model. Hear Jour 1997; 50 (10): 49-52.

13. Northern J & Meadows-Beyer C: Reducing hearing aid returns through patient education. Audiology Today 1999; 11 (2): 10-13.

14. Kochkin S: Reducing hearing aid returns with consumer education. Hearing Review 1999; 6 (10): 18-23.

15. Ross M & Bakke M: Large-area listening systems. The Hear Jour 2000; 53 (6): 52-61.