A survey on what dispensing professionals and their patients think about FLT

An informal survey of Sonus franchise members on their use of frequency-lowering technology (FLT), as well as views from select patients, suggests that FLT is a useful tool in the hearing aid dispensing armamentarium.

Not long ago, the author had a conversation with a sales rep from one of the major hearing aid manufacturers. He remarked that it was looking as if frequency-lowering technology (FLT) would become the “next big thing” in hearing aids, and I asked if the sales rep’s company had any plans to look at incorporating FLT in their hearing aids. His response was “Well…you know…the literature says it doesn’t work.” At first glance of the literature, this is not an unreasonable conclusion; however, when examined more closely, his statement becomes questionable.

Paul Teie, MS, is the professional development coordinator of the East Coast for Amplifon USA.

The two informal surveys in this article were administered to shed more light on:

- The manner in which FLT is prescribed by clinicians, and

- The benefit that patients with FLT accrue as compared to a similar group of patients with more conventional hearing aid technology.

Given that FLT is frequently prescribed for patients with hearing losses who were once given up as a “lost cause,” outcomes commensurate with those attained by patients with more conventional hearing losses and technology would be desirable.

Patients with precipitous high frequency hearing loss have presented challenges to hearing care professionals since hearing aids were first dispensed. Precipitous high frequency hearing loss can have serious effects on speech understanding. High frequency speech components, particularly voiceless consonants, may be inaudible. In these instances, attempts to make these sounds audible are usually fruitless due to the dearth of sensory cells in the region of the cochlea responsible for the coding of these sounds, or even the presence of cochlear dead regions. Conventional amplification schemes can be of limited or no utility with this kind of hearing loss.

The rationale behind frequency-lowering technology is to take spectral information from the high frequencies and relocate that information in a lower frequency area where hearing function is more intact. An excellent review of frequency-lowering technology is found in Robinson et al.1

Review of the Literature

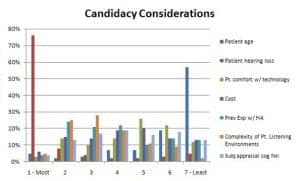

Figure 1. Candidacy considerations for the use of FLT as reported by dispensing professionals (n=181).

As the above-mentioned sales rep alluded to, several recent studies show little or no advantage for FLT over more conventional hearing aid technology in consonant identification and word recognition tasks.2-6 However, even in studies where statistical significance was not achieved, there were frequently individuals who excelled with FLT.1,3,7 Although children are not the subject of this article, the literature makes it quite clear that children do particularly well with FLT and respond to it quickly and enthusiastically.7-9

There are mixed reviews for the performance of FLT in noise. Bohnert et al10 reported enhanced performance in noise for 7 of 11 subjects. However, no such improvement was seen in two other studies that included performance in noise among their test protocols.6,9 In a recent study at Walter Reed Medical Center, QuickSIN results were essentially identical regardless of whether FLT was active.6

Kuk and colleagues have pointed out that, historically, FLT has not always been adequately understood and applied, especially in terms of individual start frequency and adjustments,11-13 and that a number of lessons/guidelines should be considered when fitting hearing aids using FLT.14

Survey of Real-World Use of FLT

Phase 1: Practice survey. An e-mail survey was sent to audiologists and hearing instrument specialists associated with Sonus™, Elite Hearing Network™, and HearPO™ divisions of Amplifon USA™. This survey asked about patient selection criteria, audiometric criteria, and return rates for frequency-lowering (FL) and non-frequency-lowering (non-FL) hearing aids. In the online version of this article (see February 2012 HR Archives at www.hearingreview.com), Appendix 1 provides the list of questions asked to providers. Of the 1,343 e-mails requesting participation, 181 individuals responded with completed surveys (13.5% completed return rate). Of the responders, 36 indicated they would be willing to participate in the second phase of the survey.

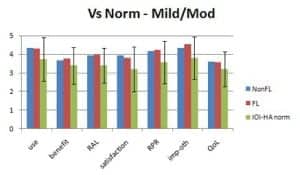

Figure 2. Mean results for patients self-reporting no hearing loss or mild/moderate hearing loss.

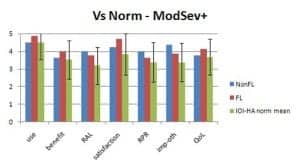

Figure 3. Mean results for patients self-reporting a moderately severe or poorer hearing loss.

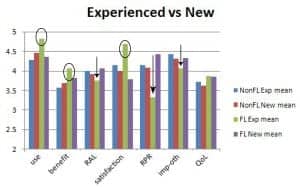

Figure 4. IOI-HA mean results comparing FL and non-FL, as well as new and experienced wearers. Experienced users who have FTP technology rate themselves relatively high in use, benefit, and satisfaction, denoted by circles. However, these same users also rate themselves relatively low in residual activity limitations (RAL), residual participation restrictions (RPR), and imposition on others (imp-oth) denoted by arrows.

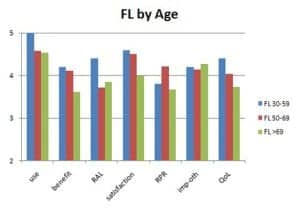

Figure 5. IOI-HA mean scores for patients using FL technology by age-group.

Phase 2: Patient survey. Each of the participants in the second phase of the survey was sent five surveys to be mailed to patients who had been fit with FLT hearing aids, and five surveys to be sent to patients fit with non-FLT hearing aids. All patients were to have had their current hearing aids for at least 2 months. Providers were asked to roughly match the FLT and non-FLT survey recipients in terms of their age and previous experience with hearing aids.

The patient surveys also included questions regarding the participants’ age and previous experience with hearing aids. The remainder of the questions comprised the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA).15

Phase 1—Provider Results

Among the respondents to the survey, FLT had been prescribed by 76% of the participants, with 24% reporting they had not fit FLT within the last year.

Most who did not fit FLT reported that one of the main reasons is that they do not dispense hearing aids by the manufacturers that offer the technology. A quarter of the responders said that they were not convinced the technology works and, perhaps with similar thinking, 18% did not think the literature is clear relative to FLT benefit. A quarter also stated that they had no patients they considered candidates for FLT. For providers who did not fit FLT circuitry, this completed the survey.

For providers who had prescribed FLT hearing aids, the largest number of responders (38%) reported that they fit less than 1 patient per month (0-10 per year); 31% fit between 11 and 30 per year; and another 31% fit more than 30 in the last year.

The purpose of the next question was to determine how providers define “precipitous” with cut-off frequencies specified “with a precipitous drop thereafter.” Close to half (44%) of respondents indicated they were willing to fit FLT for normal/near-normal (N/Nn) thresholds up to 2 kHz, while 25% and 19% were willing to fit hearing losses with N/Nn thresholds at 3000 and 4000 Hz, respectively. A total of 41% of providers considered FLT for any configuration of hearing loss.

Regarding determination of candidacy, 93% believed that all age groups were candidates for FLT. Therefore, it was not surprising that the patient’s age was the least important selection consideration for the majority of the respondents (57%). Hearing loss was the most important criterion for the majority (76%). The provider’s subjective appraisal of the patient’s cognitive function and the cost of the hearing aids were the attributes that elicited the most ambivalent responses, with no real consensus and little strong feeling about these criteria.

Other than the patient’s hearing loss, the survey shows that two other reasonably important considerations for FLT candidacy are the complexity of the patient’s listening situations (58% ranked this 1, 2, or 3) and the patient’s previous experience with hearing aids (49% ranked this 1, 2, or 3). For most of the participants, the patient’s comfort level with technology was not an important consideration for candidacy (60% ranked it as 5, 6, or 7 on the 7-item choice list).

Most practitioners indicated that it was neither an advantage nor a disadvantage (76%) to have had previous experience with hearing aids to be successful with FLT. For those thinking previous hearing aid use had an effect on success, the responses were evenly split at 10% advantage and 9% disadvantage.

About three-fourths (74%) of respondents reported a 0% to 5% return rate for FLT. For 78%, the return rate for FLT was the same as their non-FLT hearing aid return rate. A total of 17% reported that return rate for FLT was lower than their conventional return rate, and 5% said that it was higher.

Phase 2—Patient Survey Results

From the 36 participants in Phase 1 of this survey who indicated a willingness to participate in Phase 2, a total of 53 patient responses—32 with FLT and 21 with non-FLT—were received. The only ways in which participants were asked to grossly match recipients of the survey were by previous use of hearing aids and by age. Matching of ages showed a mean age for the non-FLT group of 67.1 years and 66.6 years for the FL group. For the non-FL group, 33% had previous experience with hearing aids (67% no experience); for the FL group, 56% had previous experience with HA (44% no experience).

IOI-HA. The IOI-HA surveys patients’ experience with hearing aids in terms of:

- Use-hours

- Benefit—how much do the aids help?

- Residual activity limitations—what activities continue to be limited for the patient?

- Satisfaction—are the hearing aids worth it?

- Residual participation restrictions—how much are things affected by hearing difficulties?

- Imposition on others—are others bothered?

- Quality of life

- Quantification of unaided hearing—determination of the set of norms to which data can be compared.

The IOI-HA employs two sets of norms to compare hearing aid outcomes. These are based on self-reported degree of hearing loss. In Figure 2, one can see the results of the current survey as compared to IOI-HA norms for individuals reporting they have no hearing loss or mild/moderate hearing loss, and in Figure 3 for individuals self-reporting moderately severe or poorer hearing. Mean results for both the non-FL and FL group are well within the standard deviation of the IOI-HA norms for both groups.

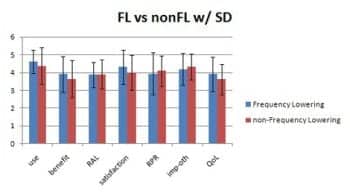

Figure 6. Comparison of mean IOI-HA results for FL and non-FL groups with standard deviations. None of these reached statistical significant difference.

When looking at mean data for survey participants in terms of technology (FLT and non-FLT) and previous hearing aid use, it is interesting to note that experienced users who are now using FLT are, on average, quite pleased with their hearing aids in terms of use, benefit, and satisfaction (Figure 4, circled results). Since FLT is frequently prescribed for “extreme” hearing losses for which conventional amplification is less-than-ideal, it may be that these patients are experiencing benefit they had not previously achieved with non-FLT amplification.

At the same time, these individuals rate themselves more poorly in terms of residual activity limitations, residual participation restrictions, and imposition on others (Figure 4, arrows). It may be that, although these patients perceive FLT as beneficial, they tend to persist in behaviors (limiting activities and restricting participation) and attitudes (the idea that they are imposing on others) developed when they used hearing aids providing less benefit.

Mean responses for all age groups were positive for all outcomes (Figure 5). The youngest responders had slightly better mean scores; however, there were only 5 responders in that age group for the FL technology.

In a comparison of FL vs non-FL responders on the IOI-HA items, Mann-Whitney U-analysis showed that, for all questions, there was no significant difference (p<.05) between the two groups (Figure 6). Overall, in the surveyed group, this suggests that the FLT and non-FLT fittings were comparable in those areas assessed by the IOI-HA questionnaire.

Provider and Patient Results Summary

According to this survey, when FLT is employed in the real world:

- FLT has been embraced by three quarters of the providers surveyed.

- Providers tend to determine candidacy primarily on the basis of hearing loss, but…

- 41% of providers do not limit candidacy for FLT to precipitous hearing loss;

- Return rates are no greater for FLT than for conventional technology, with 17% reporting FLT return rates lower than those for conventional hearing aids; and

- Patients respond to this technology at levels of benefit commensurate with more conventional technology.

Although more research using a larger sample size and an independent survey of patients would be beneficial, this survey of clinics suggests that frequency-lowering technology does work at least as well as its more conventional alternative for the patients selected. This is true in terms of benefit, as shown by IOI-HA results, as well as by the fact that providers report returns for FLT at the same levels as conventional hearing instruments. When considering the types of hearing losses most frequently addressed by FLT, this would appear to be an endorsement for the technology.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Paul Teie, MS, at .

References

- Robinson J, Baer T, Moore B. Using transposition to improve consonant discrimination and detection for listeners with severe high-frequency hearing loss. Int J Audiol. 2007;46:293-308.

- Nyffeler M. Study finds that non-linear frequency compression boosts speech intelligibility. Hear Jour. 2008;61(12):22-26.

- Robinson J, Stainsby T, Baer T, Moore B. Evaluation of a frequency transposition algorithm using wearable hearing aids. Int J Audiol. 2009;48:384-393.

- Simpson A, Hersbach A, McDermott H. Improvements in speech perception with an experimental nonlinear frequency compression hearing device. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:281-292.

- Simpson A, Hersbach A, McDermott H. Frequency-compression outcomes in listeners with steeply sloping audiograms. Int J Audiol. 2006;45:619-629.

- Walden TC. Walter Reed Hearing Aid Research Panel: Frequency lowering acclimatization study. Presented at: Maryland Academy of Audiology 19th Annual Convention, September 8, 2011, Turf Valley, Md.

- Glista D, Scollie S, Bagatto M, Seewald R, Parsa V, Johnson A. Evaluation of nonlinear frequency compression: clinical outcomes. Int J Audiol. 2009;48:632-644.

- Auriemmo J, Kuk F, Lau C, et al. Effect of linear frequency transposition of speech recognition and production of school-age children. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20:289-305.

- Wolfe J, John A, Schafer E, Nyffeler M, Boretzki M, Caraway T. Evaluation of nonlinear frequency compression for school-age children with moderate to moderately severe hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol. 2010;21:618-628.

- Bohnert A, Nyffeler M, Keilmann A. Advantages of a non-linear frequency compression algorithm in noise. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:1045-1053.

- Kuk F, Keenan D, Korhonen P, Lau C. Efficacy of linear frequency transposition on consonant identification in quiet and in noise. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20:465-479.

- Kuk F. Critical Factors in Ensuring Efficacy of Frequency Transposition, Part 1: Individualizing the start frequency. Hearing Review. 2007;14(3):60-66. Available at: www.hearingreview.com/issues/articles/2007-03_10.asp. Accessed January 9, 2012.

- Kuk F. Critical Factors in Ensuring Efficacy of Frequency Transposition, Part 2: Facilitating initial adjustment. Hearing Review. 2007;14(4):90-96. Available at: www.hearingreview.com/issues/articles/2007-04_07.asp. Accessed January 9, 2012.

- Kuk F, Keenan D, Peeters H, Korhonen P, Auriemmo J. 12 lessons learned about linear frequency transposition. Hearing Review. 2008;15(12):32-41. Available at: www.hearingreview.com/issues/articles/2008-11_05.asp. Accessed January 9, 2012.

- Cox R, Stephens D, Kramer S. Translations of the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA), Int J Audiol. 2002;41:3-26.

Citation for this article:

Teie P. Clinical Experience With and Real-World Effectiveness of Frequency-lowering Technology for Adults in Select US Clinics Hearing Review. 2012;19(02):34-39.