A new combination hearing aid/tinnitus sound generator device, ReSound LiveTS, is designed to provide significant benefit in improving the patient’s perception of their tinnitus. The authors present the rationale behind the device and two field studies on its use within tinnitus treatment programs.

Tinnitus is a concern for many people, and it affects approximately 10% to 15% of the overall population with approximately 3% to 5% of the population suffering from clinically treatable tinnitus.1 The vast majority have hearing loss in addition to their tinnitus, and as many as half of patients reporting to a typical clinic have tinnitus complaints.2,3 Use of hearing instruments or sound-generating devices in tinnitus treatment can improve outcomes,2-4 yet very few products have been designed specifically to be components of a tinnitus treatment and counseling support program. ReSound Live™TS is an advanced combination hearing instrument and Tinnitus Sound Generator (TSG) device that can be used to address both hearing loss and tinnitus.

What Is Tinnitus and What Causes It?

Tinnitus is an involuntary perception of sound that originates in the head.1 It is most commonly referred to as “ringing in the ears,” but can take on a number of perceptual characteristics, such as clicking, chirping, or pulsing. It can be constant and steady, or it can be intermittent. The perception of tinnitus can greatly vary from person to person, and psychological factors play a large role.5

Outside of known medical complications that may lead to tinnitus, it is important to note that the exact mechanism of tinnitus causation is unknown. Of the various theories and models of tinnitus causation, one of the more studied and well-accepted neurophysiological models discusses the role of cochlear damage relative to tinnitus causation. This model postulates that, when the outer hair cells (OHC) are damaged, they are no longer able to inhibit the neuronal firings of the inner hair cells (IHC) in the absence of auditory input. When the OHCs are no longer able to perform this function, the IHCs spontaneously fire neurons to the brain, which are processed, amplified, and recognized as noise, even in the absence of auditory input. This noise is tinnitus.

The severity of a person’s tinnitus is not only due to cochlear damage, but to the focus that one puts on the tinnitus. This is called prioritization. The more focus, or priority, a person puts on their tinnitus, the more audible it will be, and the more easily the brain will be able to detect the neuronal patterns that characterize it—even in the presence of other auditory input such as background noise or speech. Most people can actually ignore and habituate to the tinnitus quite easily, and their tinnitus blends into the background without much further notice. But, for some individuals, this is not the case.

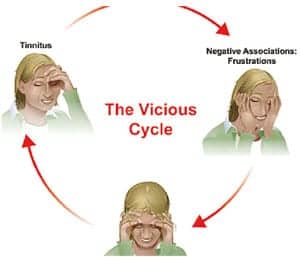

When the tinnitus becomes a focal point, negative emotions such as frustration, anxiety, and helplessness can become associated with the tinnitus. These negative emotions, which involve the limbic system, can lead to physical changes and reactions in the body, such as stress, thereby involving the autonomic nervous system.5,6

|

| FIGURE 1. The vicious cycle of tinnitus. |

When a person is stressed by the situation, the tinnitus remains, or worsens, which prompts the cycle to repeat itself. This is often referred to as the “Vicious Cycle of Tinnitus” (Figure 1). Apart from tinnitus that is caused by a known medical complication, most agree the goal of tinnitus treatment is to break the vicious cycle, and find a way for the person to gain control of their reactions to the tinnitus and ultimately learn how to habituate to it.

Habituation is the process by which one becomes “used to” the stimulus. A good example of this is air conditioner noise. Most normal-hearing people will hear the air conditioning noise when they walk into an unfamiliar room, since the air conditioning stimulus is new to the brain. However, they quickly learn to put the noise in the back of their mind, and focus on more important stimuli. When the air conditioning noise is no longer recognized by the individual, habituation to it has occurred.

By breaking the vicious cycle, individuals can still attend to their tinnitus, but rather than react negatively to it, they are aware and accepting of the tinnitus. This can result in greater control of how one reacts to their tinnitus. Ultimately, the goal over time is to habituate to the tinnitus altogether, although complete habituation may not occur in many individuals.

Tinnitus Treatments and Counseling Methods

|

| FIGURE 2. Sound therapy analogy – the candle intensity is decreased at a busy dinner table as opposed to being isolated in the dark. |

Sound therapy. There are many different types of tinnitus treatments, with one of the most common being sound therapy (also referred to as acoustic therapy). Sound therapy is simply the introduction of an external sound to help reduce the contrast of the tinnitus against the background. By increasing the level of external sounds in the patient’s environment, the perception of the tinnitus can often be decreased. A common example to illustrate sound therapy is the “candle on the table” analogy. A candle lit on a table in a dark room becomes the focal point, as it is very easy to detect the light against the dark background. In contrast, the same candle on a table in a lit room with dinnerware and a busy restaurant environment becomes less noticeable against the background (Figure 2).

There are many different tools that can be used in sound therapy, including hearing instruments and wearable sound-generating devices. Other tools that can be used are sound pillows and table-top sound generators, which generate noise and can be useful for people who have difficulty sleeping. These devices are often classified under the general rubric of tinnitus sound generators.

Common everyday sounds, such as TVs, radios, fans, or even opening a window to hear environmental sounds from outside can also be useful. In addition, music can be a very helpful form of sound therapy. In its simplest form, sound therapy is the introduction of an external sound to help “drown out” the tinnitus, and allow the individual to habituate to it.

Dedicated treatment approaches. Other well-known and commonly practiced tinnitus treatment approaches are tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) and, more recently, Progressive Tinnitus Management (PTM). Both TRT and PTM have well-defined protocols, where an emphasis is placed on educating patients about their tinnitus. Both TRT and PTM aim to provide patients with a better understanding of where tinnitus comes from, as well as understanding their reactions to their tinnitus. The goal is, through knowledge and understanding, for patients to have more control over their emotions and reactions to the tinnitus, allowing them to more efficiently cope with and ultimately habituate to their tinnitus.6

A main difference between the two treatment options is that PTM has a 5-tier hierarchal approach. Not all patients are exposed to every tier of the treatment process, but rather move on to the treatment tier that is relevant for them. Sound therapy (although not necessarily a TSG device) is an integrated part of TRT and PTM.

Outcome measures for tinnitus treatment. Regardless of what method is chosen, monitoring the status of any treatment plan is important. Outcome measures are often carried out by common tinnitus questionnaires, such as the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (THQ), or Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ). These provide for the monitoring of various aspects of the tinnitus and how it is affecting the individual.

In addition, allowing the patient to discuss how the treatment is working and how it is affecting their tinnitus can lead to important insights on the part of the clinician as well as the patient. Both types of feedback contribute to a full understanding of the effects a tinnitus treatment plan is having on the patient.

Lastly, creating realistic expectations from the start is crucial. As full habituation may not take place for all, and tinnitus treatment can take an extended period of time (6 months to 2 years or longer for some), it is important that the patient’s expectations are in line with the treatment objective.

A Combination Device for Hearing Loss and Tinnitus

ReSound Live™TS is a fully functional and flexible combination hearing loss and tinnitus solution to assist in your treatment of tinnitus/hearing loss sufferers. It offers a cosmetic and customizable solution to help treat tinnitus, with the goal of providing more relief and a better quality of life. The hearing instrument portion of ReSound LiveTS offers all the advanced digital technology of the ReSound Live™ hearing instruments, but also offers unique TSG features, such as frequency shaping of the noise signal, amplitude modulation, and Environmental Steering.

Because this device can be implemented in an open-fit configuration, it can also allow more natural sound through the ear canal. For individuals with milder hearing losses, simply providing amplification through the open-fit hearing instrument is oftentimes enough sound therapy to help them habituate to their tinnitus, even without the TSG.7,8

Most literature suggests that using a broadband stimulus activates the most neurons and is most effective for sound therapy. Therefore, the default noise setting for LiveTS is set to a broadband filtering setting, but it has the flexibility of low- and high-cut controls to provide more individualized comfort. The low-cut filter range is 250 Hz to 2000 Hz, while the high-cut filter range is 2000 Hz to 6000 Hz.

|

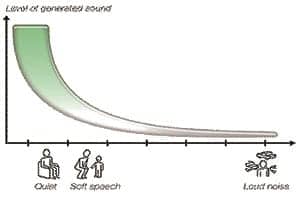

| FIGURE 3. Environmental Steering – The tinnitus sound generator volume will automatically adjust according to listening environment. |

Another feature that can be personalized for patient comfort is amplitude modulation. Amplitude modulation (AM) is a fluctuation in the level of the noise signal while all other spectral components remain uniform. AM attenuation in LiveTS is non-deterministic (randomized) to avoid audible periodicity (ie, the amount of attenuation will not always be the same). In the fitting software, different levels of modulation and modulation speeds can be selected according to the patient’s preferences.

Environmental Steering is a unique feature in LiveTS that acts as an automatic volume control; it adjusts the level of the white noise signal according to the listening environment. It uses a classifier that assigns the input into one of seven listening environments (Quiet, Soft Speech, Loud Speech, Soft Speech in Noise, Loud Speech in Noise, Moderate Noise, and Loud Noise). Because people typically report that their tinnitus is worse in quiet situations, when the user is in a quiet environment, the TSG volume will be programmed to the Quiet setting. When the user is in a more speech-heavy (noisy) environment, less noise is needed to decrease the contrast of the tinnitus, since there is more environmental stimuli present, and thus the TSG volume is decreased (Figure 3).

Environmental Steering serves a number of purposes. First, for users who are not familiar with a manual volume control—or do not fully understand the aim of sound therapy—Environmental Steering can help avoid the potential risk of completely masking the tinnitus. Completely masking the tinnitus does not allow for habituation (ie, one cannot habituate to what is not audible) and this can be detrimental in a tinnitus treatment program.

Environmental Steering also ensures that the TSG signal does not interfere with important information, such as speech. Finally, eliminating the need for a manual volume control puts less emphasis on the instrument and, for some, helps reduce the attention that is paid to the tinnitus. This can occur if one is constantly adjusting the volume control. If Environmental Steering is not preferred, a manual volume control can be activated. This provides a greater sense of control for some users. Environmental Steering or the manual volume control can be activated according to the patient’s preferences.

Two Research Studies Using the Combination Hearing Aid/TSG

Study A and B were multi-facility external trials conducted at well-established tinnitus clinics worldwide to evaluate the benefit of the ReSound LiveTS combination instrument in regard to tinnitus treatment. The studies also focused on finding mixing point information, Environmental Steering, and amplitude modulation preferences—all important functions of the LiveTS instrument. It is important to note that both trials used some form of counseling and treatment (eg, TRT) in combination with using LiveTS as a sound therapy device.

Study A design and results. This study involved 30 tinnitus patients falling within Jastreboff’s tinnitus Category 1 and 2.6 Subjects presented with mild and moderate bilateral hearing losses. All had suffered from tinnitus for at least 6 months, and patients with Menière’s disease and middle or external ear disease were excluded.

|

| FIGURE 4. Pre- and post THI questionnaire results |

|

| FIGURE 5. Pre- and post Structured Interview results |

After fitting the LiveTS receiver-in-the-ear instruments, Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT) was administered for 6 months, and the effect of the treatment was evaluated using the Structured Interview,9 TRI Tinnitus Patient Assessment and Outcome Measurement,10 and THI self-administered questionnaire.11

Assessment results were collected at the initial fitting, and again after 3 months and 6 months. Figure 4 shows the development in the 6-month time frame of THI scores, and Figure 5 shows the Structured Interview VAS scores for “annoyance,” “intensity,” and “tinnitus effects on patient’s life.” After 6 months, all differences are significant (THI: p=0.001; annoyance and intensity: p <0.001; life effect: p=0.002).12

Study B design and results. A total of 24 subjects with varying perceptions of tinnitus were recruited for this trial. Of the subjects, 13 had varying degrees of sensorineural hearing loss with thresholds falling within the mild-to-moderate range, and 11 had no significant hearing loss.

The subjects were fit with LiveTS receiver-in-the-ear devices, with 22 subjects fit binaurally and 2 subjects fit monaurally. They were seen over a period of approximately 6 months for 5 visits. The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) and Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (THQ) were administered at the initial, mid, and final visits to evaluate how the subjects perceived their tinnitus following the fitting.

Half the test subjects were fitted with the Environmental Steering enabled at the first visit, and the other half with the volume control enabled. Approximately 4 weeks after the initial visit, the sound level adjustment (ie, Environmental Steering and manual VC) was switched to the opposite of what they were initially fitted with. The test subjects then rated their preferences on a take-home questionnaire.

Amplitude modulation was evaluated by initially giving all subjects two programs: one with modulation and one without. Approximately 2 weeks after the initial visit, all subjects were asked how they perceived the modulation and then chose one TSG program, either with or without modulation. This TSG program was adjusted based on their preferences.

In analyzing the results of Study B, a total of 20 of the 24 subjects answered the THQ and 16 answered the THI. The subjects revealed a significant improvement in their tinnitus questionnaire scores over a period of 6 months, which was documented by an improvement in their THQ and THI scores. On average, their THQ scores dropped significantly from 50.8 at the beginning of the trial to 33.0 at the end of 6 months (p<0.05), and the THI scores also dropped significantly from 58.4 at the start to 29.9 at the end of 6 months (p<0.05).

As far as the features of the TSG, 68% of the subjects preferred the volume control over Environmental Steering, and 73% preferred continuous noise over modulated noise. Approximately 82% of the subjects preferred the filter settings to allow broadband noise (ie, 500-6000 Hz), while 18% preferred more narrow-band filter settings.

In conclusion, these trials revealed ReSound LiveTS to provide significant benefit in improving the patient’s perception of their tinnitus within tinnitus treatment programs. The various feature options make LiveTS a very flexible tinnitus solution, allowing the professional to personalize the fit according to patient preference.

References

- McFadden D. Tinnitus: Facts, theories, and treatments. Report of Working Group 89, Committee on Hearing Bioacoustics and Biomechanics. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1982.

- Kochkin S, Tyler R. Tinnitus treatment and the effectiveness of hearing aids: hearing care professional perceptions. Hearing Review. 2008; 15(13):114-18. Accessed September 9, 2010.

- Kochkin S, Tyler R. Tinnitus treatment and the effectiveness of hearing aids [Hearing Review Science & Technology Thursday Podcast]. Accessed September 9, 2010.

- Searchfield G, Kaur M, Martin WH. Hearing aids as an adjunct to counseling: tinnitus patients who choose amplification do better than those that don’t. Int J Audiol. 2010;49:574-579.

- McKenna L, Andersson G. Changing reactions to tinnitus. Hearing Review. 2007;14(9):12-21. Accessed September 9, 2010.

- Henry JA, Jastreboff MM, Jastreboff PJ, Schechter MA, Fausti SA. Assessment of patients for treatment with Tinnitus Retraining Therapy. J Am Acad Audiol. 2002;13:523-544.

- Del Bo L, Ambrosetti U, Bettinelli M, Domenichetti E, Fagnani E, Scotti A. Using open-ear hearing aids in tinnitus therapy. Hearing Review. 2006;13(9):30-32. Accessed September 9, 2010.

- Del Bo L, Jastreboff M, Parazzini M, Ravazzani P. Open ear amplification in tinnitus therapy: an efficiency comparison with custom sound generators. Paper presented at: IX International Tinnitus Seminars; Göteborg, Sweden; 2008.

- Jastreboff PJ, Jastreboff MM. Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT) as a method for treatment of tinnitus and hyperacusis patients. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000;11:162-177.

- Langguth B, Goodey R, Azevedo A, Bjorne A, Cacace A, Crocetti A, Del Bo L, De Ridder D, Diges I, Elbert T, Flor H, Herraiz C, Ganz Sanchez T, Eichhammer P, Figueiredo R, et al. Consensus for tinnitus patient assessment and treatment outcome measurement. Prog Brain Res. 2007;16:525-536.

- Newman CW, Sandridge SA, Jacobson GP. Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J Am Acad Audiol. 1998;9:153-160.

- Carraba L, Coad G, Costantini M, et al. Combination open ear instrument for tinnitus sound treatment. N Z Med J. 2010;123(1311):136-140. Available at: . Accessed September 9, 2010.

Citation for this article:

Piskosz M, Kulkarni S. An innovative combination device to assist in tinnitus management. Hearing Review. 2010;17(11):26-30.