Hearing experts at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine and several other institutions are conducting an ABI trial aimed at helping children born without a hearing nerve. The 3-year clinical trial, launched in March 2014, has successfully implanted an auditory brainstem implant (ABI) device in 4 children who previously could not hear. According to a recent announcement, the research team presented preliminary findings at the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) 2015 Annual Meeting in San Jose, California, on February 14, 2015. The research team’s findings thus far have been generally positive.

“Initial activation of the ABI is like a newborn entering the world and hearing for the first time, which means these children will need time to learn to interpret what they are sensing through the device as ‘sound,’” said audiologist Laurie Eisenberg, PhD, a Keck School of Medicine of USC otolaryngology professor and study co-leader. “All of our study participants whose ABIs have been activated are progressing at expected or better rates. We are hopeful that, with intensive training and family support, some of these children might develop auditory skills similar to those of children with cochlear implants.”

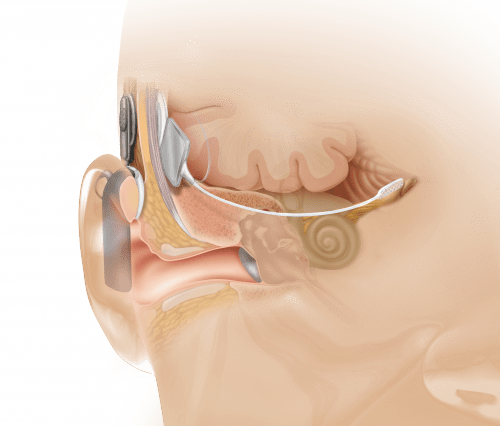

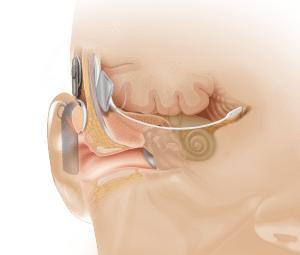

As previously reported in a July 2010 article in Hearing Review, Dr Eisenberg has had extensive experience working with children and hearing devices, including the first pediatric cochlear implant. According to Dr Eisenberg and colleagues, hearing loss manifests in various forms, most of which can be partially restored through hearing aids and cochlear implants. However, those devices cannot help a small population of individuals who do not have a cochlear nerve, or hearing nerve, that sends sound signals to the inner ear. For people without a hearing nerve, there is no way to perceive sound, even with a hearing aid or cochlear implant. The ABI is considered to be a revolutionary device because it bypasses the inner ear entirely, stimulating neurons directly at the human brainstem.

Anatomical view showing ABI placement, which bypasses the cochlea or inner ear (photo courtesy of Cochlear Inc).

In the United States, the ABI is approved for use only in patients 12 years or older who have neurofibromatosis type II, an inherited disease that causes a non-malignant brain tumor on the hearing nerve. The ABI has shown limited effectiveness in adults in these cases. Scientists believe that the ABI would be more effective in younger children, because their brains are more adaptable. The current clinical trial will attempt to prove that the ABI surgery is safe in young children, and will allow researchers to study how the brain develops over time as it adapts to learning to hear sound and develop speech with the help of the ABI.

The scientists report that surgeons outside the United States have been doing ABI surgeries in children for more than 10 years, but there has never been a formal safety or feasibility study under regulatory oversight.

“Hearing loss can be devastating to a child’s social development, and for some children, the ABI is their last viable chance to hear,” said Keck School of Medicine of USC Professor Robert V. Shannon, PhD, an investigator for the trial and a leading scientist in the development of ABI technology since 1989. “Several of the young children who had ABIs implanted outside the United States have sought help at the USC-CHLA Center for Childhood Communication and we know that they now have the potential to understand speech. This really shows how powerful and flexible the brain is. By studying how the brain and the hearing system work together through this device, our team will set the gold standard for use of this technology.”

According to the Keck School of Medicine, the NIH clinical trial grant covers the costs of the ABI device, procedure, and subsequent testing. To qualify for participation, pediatric patients must show that standard treatment for hearing loss, such as hearing aids and cochlear implants, have been ineffective.

More information about the ABI and its benefits can be found in an article by audiologists Margaret Winter, MS, and Steve Otto, MA, that appeared in the Winter 2013 edition of the Hearing Products Review.

Source: Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California (USC)

Photo credits: Keck Medicine of USC; Cochlear Inc