Tech Topic | October 2022 Hearing Review

By Jennifer Groth, MA, and Andreas Jahn, MsC

Jabra Enhance Plus high-tech hearing enhancement earbuds will join the Jabra Enhance product line

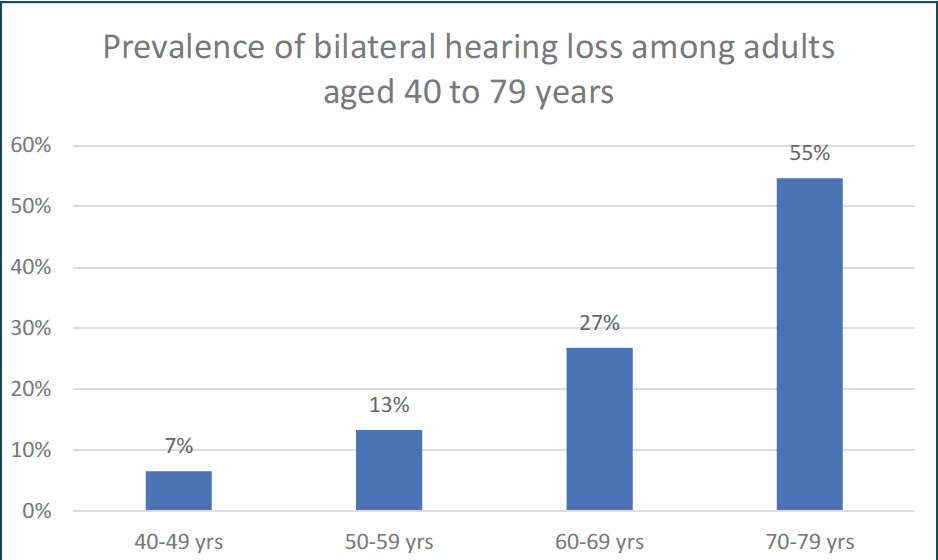

Many adults have hearing loss, and it becomes increasingly common with age; the prevalence of bilateral hearing loss is reported to be close to 7% among those between 40 and 49 years, with the percentage doubling with each decade, up to 70-79 years.1 For people over 70 years, more than half exhibit a hearing loss that can interfere with daily communication ability, (Figure 1).

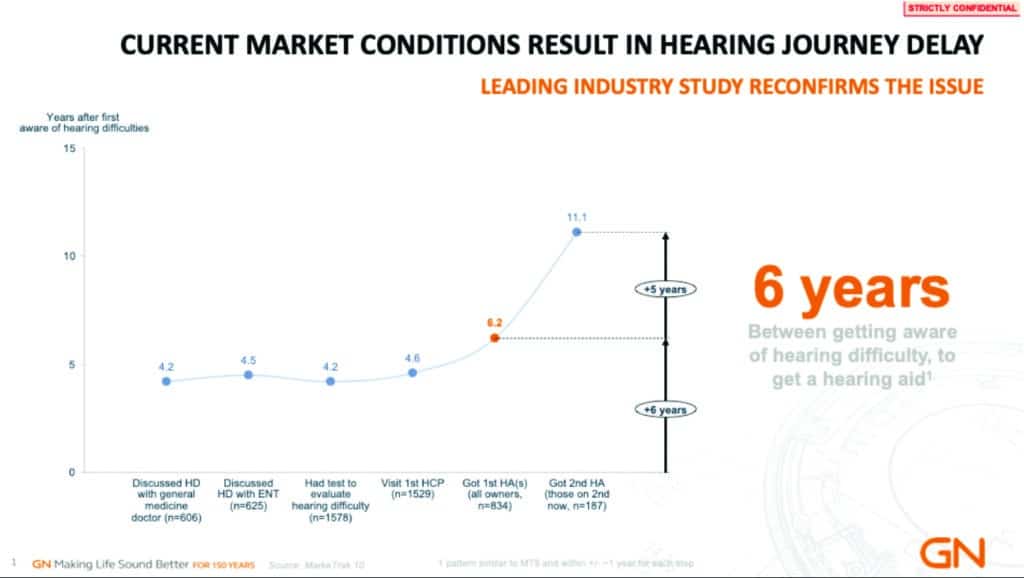

An unfortunate consequence of hearing loss being so commonplace is that it can be both overlooked and dismissed. When hearing loss is normalized and not considered a “big deal,” there is little urgency in seeking solutions. This is clearly evidenced by the years-long lag between awareness of hearing difficulty and solution seeking shown in different studies.2,3 Data from MarkeTrak 10 (Figure 2) show the average number of years survey respondents reported that it took for them to progress to each stage of their journey in acquiring hearing aids, with six years passing between awareness of hearing difficulty and beginning to use amplification.3 This is in spite of the well-supported benefits and satisfaction associated with using hearing aids. Eight of 10 people who use hearing aids report satisfaction and attribute positive changes in their quality of life to using hearing aids.4 Authors of a Cochrane review concluded that hearing aids for treatment of adults with mild-to-moderate hearing loss are effective at improving hearing-specific, health-related quality of life, general health-related quality of life, and listening ability.5 These are immediate effects that are noticeable and appreciated by those who adopt hearing aids. Long-term positive effects on health and well-being may also be associated with hearing aid use. Comorbidities of hearing loss include issues with balance as well as incidence of dementia, and hearing loss may be a modifiable risk factor for such issues via audiological intervention.6 Many millions of people with hearing difficulties are missing out on these benefits.

In the US, the underusage of hearing aids and minimal insurance coverage or subsidies to offset cost of treatment motivated a public health initiative. The act passed in 2017 was meant to enable adults with perceived mild-to-moderate hearing loss to access hearing aids over-the-counter (OTC) without being seen by a healthcare practitioner (HCP). The bill requires the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to categorize certain hearing aids as OTC and to issue rules regarding OTC hearing aids; these rules were released in August 2022. Manufacturers of hearing aids and other amplification devices have taken steps so that they are prepared to meet consumers with relevant products. With expertise in both consumer audio and hearing aids, GN Group is uniquely positioned to complement the offering of traditional hearing aids by bringing new solutions to those who experience hearing difficulties, but hesitate to seek help. To this end, GN Audio brand Jabra marries expertise in true wireless technology and consumer electronics with the hearing aid heritage of GN Hearing in the Jabra Enhance line of hearing enhancement products. The Jabra Enhance line was introduced with the Jabra Enhance Pro, a state-of-the-art hearing aid that is prescribed and fit by HCPs. Now, the Jabra Enhance Plus high-tech hearing enhancement earbuds join the Jabra Enhance line to help millions of people progress in their hearing journey with a unique choice based on extensive research into consumer behavior, hearing challenges, and solution preferences. This research revealed that underserved segments had distinct preferences regarding things like appearance and functionality of the device, as well as the purchasing experience, that set them apart from current hearing aid users.

There are multiple barriers that prevent people from seeking help for hearing difficulties. Affordability and access are widely acknowledged issues, especially among certain subpopulations.7 However, even people who do have access to affordable hearing healthcare often do not take advantage of it. Based on modest hearing aid uptake in countries where hearing aids are fully or primarily subsidized by national health systems, Valente & Amlani8 estimated that market penetration would increase by no more than 10% in the US if hearing aids were similarly subsidized. They emphasized that other significant hurdles affecting hearing aid adoption include “heightened social stigma, denial of hearing loss, and lack of self-efficacy.” The significant contribution of barriers in addition to cost is further reflected in research examining social representation of hearing aids. Chundu et al9 used a free-association task to probe the system of values, practices, customs, ideas, and beliefs surrounding hearing aids among people with hearing loss in four countries including the US. Fifty-four percent of the US participants’ associations had negative connotations, demonstrating a generally negative view of hearing aids. The two most common negative associations included “cost and time” but also “appearance and design.” This data supports that a focus on cost alone is unlikely to bring about any dramatic change in the perception of hearing aids among potential users; how amplification devices look and function is of equal importance.

In today’s market, there are already direct-to-consumer hearing aids and amplification devices that can meet cost and accessibility needs, and many similar products are expected to be introduced. With few exceptions, traditional hearing aids are designed to solve the same hearing and communication issues for anyone with hearing loss; differentiation is in terms of the severity of hearing loss that can be fit and which of the established styles the devices have. In other words, they don’t take into account the needs or wishes of a specific audience. People who do not seek help for their hearing difficulties due to barriers such as those highlighted by Valente & Amlani8 are unlikely to be moved by a lower price of what they may perceive as a cheaper version of a product they don’t want. GN Group recognized that there is an opportunity to identify and learn about potential users of an amplification product who are not drawn by traditional hearing aids, and to design the product to match their unmet needs. By taking this approach, the use of amplification can be expanded to include people who don’t seek help for hearing difficulties regardless of price and accessibility. This paper describes the insights-based rationale for the creation of Jabra Enhance Plus including how specific findings led to design decisions.

Identifying the Target Audience – Market Size

An essential question to answer when defining a target audience for a product or service is the size of that audience. There are naturally limitations in trying to make estimates from data which itself consists of estimates, and different results can arise depending on the assumptions that are made. Calculations made by GN Group based on Goman & Lin1 and MarkeTrak 10 and using a weighting function to account for hearing aid usage rates by hearing loss severity indicate a primary market size of 18 million US adults with self-perceived hearing difficulties. Based on the estimate of US adults with hearing loss in at least one ear,1 an additional 34 million people who do not perceive hearing difficulties could be considered a secondary audience. Even if our approximation of the market size is off by several million, the potential is still very large, and it is worthwhile to investigate what product qualities and what type of experience people in the target group would value.

In-depth Market Research

Given the proven and potential positive outcomes of using hearing aids, researchers have long sought to understand the barriers and triggers to seeking help for hearing difficulties, for adoption of hearing aids, and to identify characteristics associated with hearing aid adoption.10-12 This understanding could inform strategies aimed at promoting earlier adoption of amplification, and a thorough review of existing insights was merited. There were four key takeaways from this review:

■ Affordability doesn’t tell the whole story. As discussed, affordability explains why some people who could benefit from hearing aids don’t use them, but it is for many not the strongest or most significant barrier to taking action.

■ Self-perceived hearing difficulties are a prerequisite to action. A common characteristic among those who do act is self-perceived hearing difficulties.10 Put in another way, those who have hearing loss but do not recognize it as problematic will not seek help. This seems obvious but implies that it would not be efficient to design a solution for people who don’t see a personal need for it.

■ People misjudge their coping abilities and the potential help of hearing solutions. It is also noteworthy that many who perceive hearing difficulties and know they have hearing loss don’t believe that amplification will be worthwhile for them. Humes13 found that adults who did not comply with a clinical recommendation to seek treatment for hearing loss compared to those who did seek treatment had lower expectations for hearing aids and judged their communication abilities and adjustment to hearing problems as being better.

■ Professional guidance is valued. Another relevant finding is that individuals who experience hearing difficulties are greatly influenced by significant others and trusted advisors – such as family members and healthcare specialists – in their help-seeking behaviors and purchase decisions.14-16 Regarding OTC hearing aids, respondents to the MarkeTrak 10 survey who did not own hearing aids revealed a lack of confidence in purchasing an OTC solution without professional guidance.17 This suggests that a solution with some level of professional support would be attractive to potential users and runs counter to the idea that low-priced “do-it-yourself” hearing aids will motivate a majority of those who might benefit.

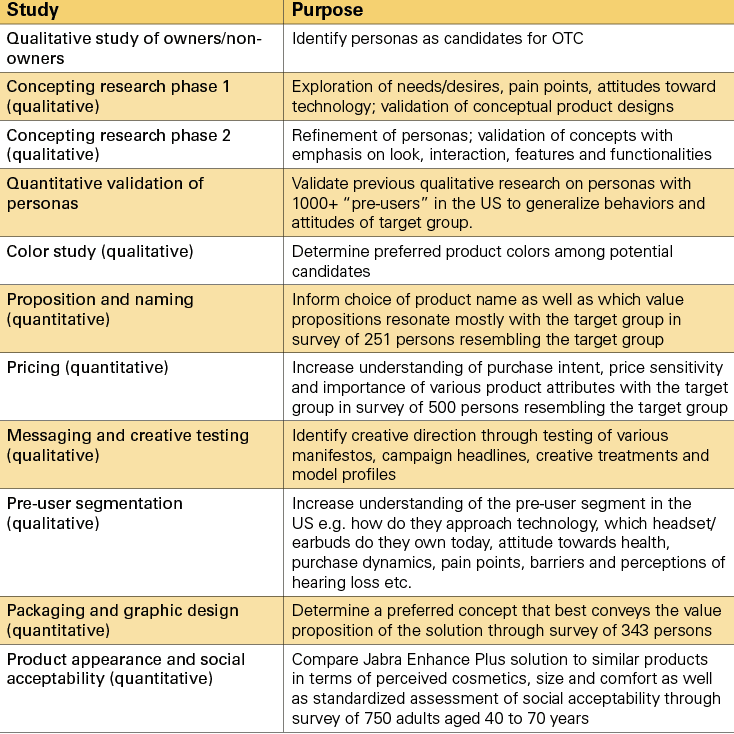

While published insights on people with hearing loss who do and do not choose to use hearing aids is a helpful starting place, more in-depth knowledge is desirable to ensure that a product connects with its target audience. This knowledge subsequently infuses everything to do with the product, including product design, functionality, packaging, marketing, and distribution, to name just a few important aspects. The goals in taking this insights-driven approach were to attract more people with hearing loss to advance more quickly in their journey to better hearing; to make it easy and accessible for them; and to ensure they felt confident in choosing, setting up, and using the solution. Prior to beginning product design and throughout the development process, GN Group carried out more than 10 quantitative and qualitative studies engaging approximately 2,000 consumers. Table 1 provides an overview of these studies.

Intrinsic Barriers and Motivators

Some of the GN Group studies were directed at understanding the potential consumer, the barriers to action, and motivators/triggers for action. The findings largely echoed those from published research:

■ Lack of acceptance of hearing loss or perception of hearing loss as “not that bad.”

■ Loss of identity and stigma associated with being a person with hearing loss; concerns about personal image and prejudicial perception of others in relation to hearing loss or using hearing aids.

■ Coping strategies for managing hearing difficulties, which could be both positive (eg, using visual cues and optimum positioning) and negative (eg, avoidance of difficult situations).

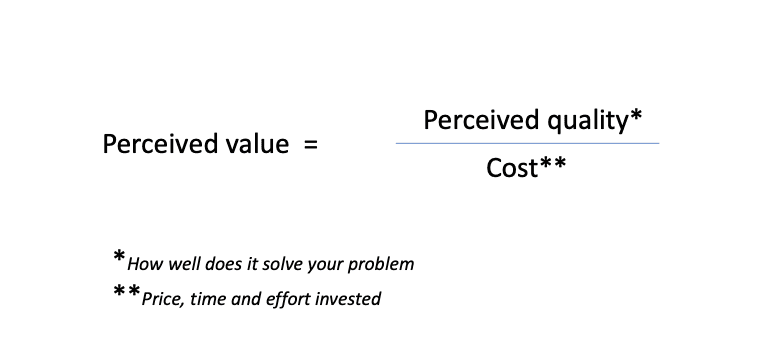

One clarifying finding was that hearing aids were viewed as a very large step to address a small perceived problem. Our analysis therefore sought to understand the nuances that contribute to this view, thereby gaining insight to unlocking interest in amplification as a way of managing hearing difficulties. We discovered five key hurdles to seeking help for hearing difficulties. One of these was indeed how much hearing aids cost. Some people do not feel they can afford hearing aids; others do not perceive a high enough value in hearing aids relative to the cost. This concept of value relates to the other identified barriers. By carefully considering these other barriers in our proposed solution, perceived value could be strongly driven by increasing perceived quality of the solution rather than simply offering low-price traditional hearing aids (Figure 3).

The second key hurdle was effectiveness of and personal compatibility with the solution. Themes in this area included concerns that hearing aids would not fit into their lifestyle, that they would not work well in solving their difficulties, and that they may be uncomfortable to use. There was also expressed reluctance to commit to the expected burden of using and maintaining hearing aids, as well as the fear of becoming dependent on them. A third barrier that emerged was, as outlined above, related to stigma and social concerns as well as aesthetics of hearing aids. A lack of knowledge about where to start and what the process in acquiring hearing aids would be was also identified as a barrier that contributes to inaction, in particular a resistance to a “medical” experience where they do not feel in control. And finally, we discovered a permeating sense that one’s hearing difficulties were not significant enough to merit treatment, despite recognition of hearing issues in situations that are important to them.

Purchase Preferences

It is key to understand how the potential user of amplification recognizes need and moves toward action. But in order to move potential users toward a solution, it is also necessary to understand what kind of purchasing experience they expect or desire. Therefore, we sought to answer many questions regarding potential users’ purchase preferences. These included how they want to research solutions, what influences their purchase decisions, how they want to make purchases, what they expect in terms of packaging and guidance, and what product characteristics were most important to them.

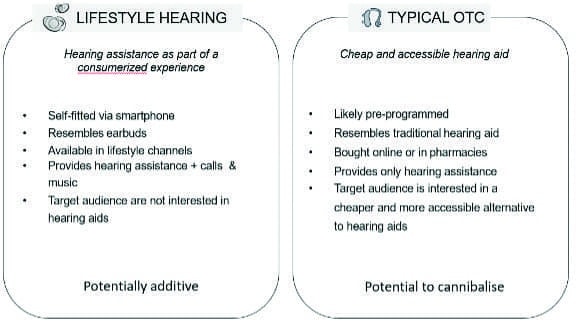

While our research led to specific decisions in product development, the most foundational outcome was crystallized in the decision to create a category of hearing enhancement products that we think of as “Lifestyle Hearing.” This category is clearly differentiated from the more generic or typical OTC, and is expected to add to existing business by growing the market rather than replacing low-cost hearing aids. One finding in our studies that supports this projected growth was a 33% greater purchase intent for proposed solutions among those aged 18 to 49 compared to people who were older (50 to 69 years). Use of traditional hearing aids among people with self-perceived hearing difficulties in this age range is exceptionally low. The two categories are summarized in Figure 4.

to the business of a hearing aid manufacturers as well as HCP practices.

Introducing Jabra Enhance Plus

Branding and Distribution

Jabra Enhance Plus is a self-fit hearing enhancement product available for purchase in multiple channels including via an HCP. The decision to distribute the product in this way was informed by the finding that consumers are interested in a consumer experience from a known and trusted brand, but backed up with medical expertise. Our studies told us that brand drives confidence in the technology and influences purchase intent significantly. Jabra is a recognized and popular brand within audio consumer electronics that can be leveraged to draw consumers and add to their perception of product quality. Furthermore, we learned that consumers like to research and learn about their options via online searches (58%) and reviews (51%) as well as social media (47%). Because Jabra is a known brand, it will be easy for potential consumers to learn about Jabra Enhance Plus in ways they prefer, such as the Jabra website. When it comes to making the purchase, the vast majority of participants in our studies preferred to purchase from a consumer electronics retailer or an HCP. Twenty-five percent would prefer to purchase via an HCP, while more than 50% would like to purchase via a consumer electronics channel. Combined with the knowledge that potential consumers of a device that they personalize themselves have expressed uncertainty in their ability to assess their hearing status, select the appropriate product for themselves, set up the product for use, and troubleshoot any issues,17 it is advantageous to make the product available for purchase via HCPs where suitability can be professionally assessed, and support could be made available. In addition, this model allows a trusted relationship between the consumer and HCP to be established, which may lead to return business when the consumer is ready for professionally fit hearing aids.

Preferred Aesthetics and Usage

Even though people who wear hearing aids recognize that untreated hearing loss is far more stigmatizing than how hearing aids look,18 the cosmetic factor remains a significant barrier to hearing aid uptake. Participants in our studies expressed a clear desire for a product that did not resemble a medical hearing aid although they did not think it needed to be hidden or invisible. This was important in reducing the perceived social discomfort people expected to experience if wearing a traditional hearing aid. They used words like “organic,” “soft,” and “round” in describing their preferences, and these became guiding principles in the design. In addition, they wished for a solution that would help them in specific situations where difficulties were experienced, such as in meetings at work or at noisy restaurants. At the same time, they wanted a consumer experience by being able to stream calls and music from their smartphones, and to use the devices as hands-free headsets for calls.

As shown in (Figure 5), the resulting product resembles earbuds, but are smaller than wireless earbuds on the market today. In fact, the Jabra Enhance Plus earbuds are 50% smaller than the the Jabra Elite 75t, which is amongst the smallest consumer wireless earbuds on the market today. They are rounded, fit discreetly in the ear with comfortable and soft Eargels, and have a finish in either anthracite and silver, or beige and gold that conveys high-quality design and workmanship. The small size is key; although the target audience does not want a device that looks like a typical hearing aid, they are also aware that wearing earbuds can cause social confusion in conversations because others aren’t sure what or who the wearer might be listening or talking to.

No compromises were made on sound quality or functionality. The Jabra Enhance Plus earbuds provide amplification for improved hearing, but also have similar capabilities to consumer wireless earbuds including a rechargeable battery and matching charging case, direct streaming of music and calls, and hands-free functionality. In an online survey of 750 adults in the target age range, Jabra Enhance Plus was judged to be as attractive, but significantly smaller and more discreet, than three other wireless earbuds from other brands. In-house trials that tested fit and comfort revealed that:

■ 98% of the adult participants reported that they could comfortably wear Jabra Enhance Plus for 4 hours or more at a time;

■ 100% of participants agreed that Jabra Enhance Plus fits securely in their ear when sitting still, and 93% agreed that it remains secure in their ears when walking or exercising; and

■ Jabra Enhance Plus was rated significantly better for comfortable and secure fit than a premium consumer wireless earbud.

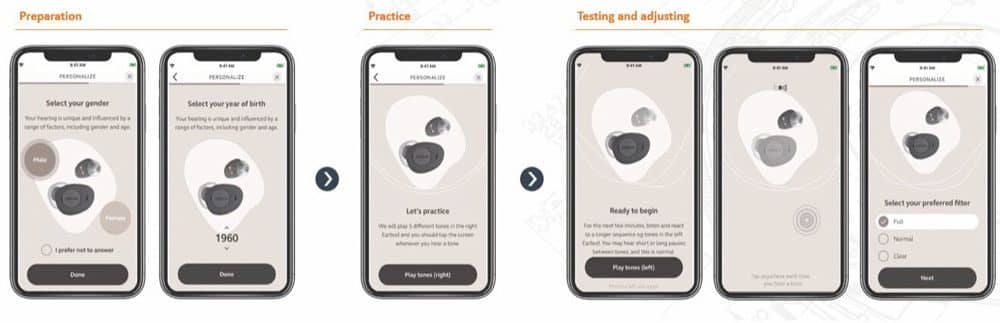

Product Setup and Self-fitting

Jabra Enhance Plus was introduced prior to the release of the OTC rules, and was thus initially sold based on guidance from HCPs. Once purchased, the experience of unboxing, setting up, and personalization of the devices is consistent with other Jabra consumer products, as our research showed a strong desire for control over this part of the experience. A key component of the system is the Jabra Enhance app., (Figure 6) illustrates the steps that the app guides the user through to determine their individual hearing profile and provide an accurate fitting (personalization). The test process itself is new technology developed by GN researchers that uses Bayesian learning to determine sound detection thresholds. This data is used to adjust the amplification of the Jabra Enhance Plus devices according to the NAL-NL2 fitting prescription for people who do not have hearing aid experience.19 Users in an in-house trial rated the Jabra Enhance app as highly usable for setup and personalization as well as daily use which supports that it is an easy-to-use tool. Using the System Usability Scale (SUS),20 5 users assigned median scores of 88 for setup/self-fitting and 90 for daily use. SUS scores above 85 indicate “excellent” usability.

Using the Jabra Enhance Plus

Participants in our qualitative studies placed high importance on having GN Hearing technology within the product. The expertise in developing solutions for hearing loss was viewed as assurance that Jabra Enhance Plus would be effective and safe for them to use. In addition, they prioritized the possibility of professional support greatly. Four key sound processing features known from advanced hearing aids developed by GN Hearing were implemented into the compact design for clear, high quality sound. These are:

■ The Warp Compressor analyzes sounds similarly to the human ear for more natural sound quality.

■ Digital Noise Reduction provides listening comfort without degrading the speech signal.

■ Digital Feedback Suppression uses phase cancellation techniques to keep feedback from interfering with quality amplification of sound.

■ Binaural Beamformer preferentially amplifies sounds coming from in front, allowing users to focus on what is important.

Once the personalization is complete, users can control the volume and sound of the Jabra Enhance Plus devices via the Jabra Enhance app. As desired by participants in our studies, Jabra Enhance Plus is engineered for situational use where hearing difficulties are experienced, but also does the job of consumer wireless earbuds by streaming audio and calls directly to the user’s ears.

Summary

Many more people could be helped by using hearing aids than currently do so, and this is a highly acknowledged problem that led to the OTC public health initiative. GN Group was prompted to examine key barriers to adoption of hearing aids. Through deep consumer research, we have taken an approach that will present something new to the underserved audience. It is designed according to their preferences, and has the potential to markedly increase penetration of use of amplification. Jabra Enhance Plus is a solution that leverages the value of the traditional model and the global trend of high-tech earbuds to start people with hearing difficulties on their hearing journey earlier. For HCPS, this can mean a new revenue stream and loyal customers who may purchase traditional hearing aids down the line.

Citation for this article: Groth J, Andreas J. Lifestyle hearing: A new category of hearing enhancement addresses key barriers that keep millions from seeking help for hearing loss. Hearing Review. 2022;29(10):14-18.

References

- Goman AM, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2016 Oct;106(10):1820-2.

- Simpson AN, Matthews LJ, Cassarly C, Dubno JR. Time from hearing-aid candidacy to hearing-aid adoption: A longitudinal cohort study. Ear and Hearing. 2019;40(3):468-476.

- Jorgensen L, Novak M. Factors influencing hearing aid adoption. Seminars in Hearing. 2020;41(1):006-020.

- Picou EM. MarkeTrak 10 (MT10) survey results demonstrate high satisfaction with and benefits from hearing aids. Seminars in Hearing. 2020;41(1):021-036.

- Ferguson MA, Kitterick PT, Chong LY, Edmondson‐Jones M, Barker F, Hoare DJ. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(9):CD012123.

- Besser J, Stropahl M, Urry E, Launer S. Comorbidities of hearing loss and the implications of multimorbidity for audiological care. Hearing Research. 2018;(369):3-14.

- Arnold ML, Hyer K, Small BJ, et al. Hearing aid prevalence and factors related to use among older adults from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2019;145(6):501-508.

- Valente M, Amlani AM. Cost as a barrier for hearing aid adoption. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2017;143(7):647-648.

- Chundu S, Allen PM, Han W, Ratinaud P, Krishna R, Manchaiah V. Social representation of hearing aids among people with hearing loss: An exploratory study. International Journal of Audiology. 2021;60(12):964-978.

- Knudsen LV, Öberg M, Nielsen C, Naylor G, Kramer SE. Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid use and satisfaction with hearing aids: A review of the literature. Trends in Amplification. 2010;14(3):127-154.

- Byun YS, Kim SS, Park SH, et al. Characteristics of patients with hearing aids according to the degree and pattern of hearing loss. Journal of Audiology & Otology. 2016;20(3):146-152.

- Pronk M, Deeg DJH, Versfeld NJ, Heymans MW, Naylor G, Kramer SE. Predictors of entering a hearing aid evaluation period: A prospective study in older hearing-help seekers. Trends in Hearing. 2017;21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/233121651774491.

- Humes LE. Differences between older adults who do and do not try hearing aids and between those who keep and return the devices. Trends in Hearing. 2021;25. DOI:10.1177/23312165211014329.

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: The key influencing factors in hearing aid purchase intent. Hearing Review. 2012;19(3):12-25.

- Amlani AM. Influence of provider interaction on patient’s readiness toward audiological services and technology. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2020;31(5):342-353.

- Ng JH-Y, Loke AY. Determinants of hearing-aid adoption and use among the elderly: A systematic review. International Journal of Audiology. 2015;54(5):291-300.

- Edwards B. Emerging technologies, market segments, and MarkeTrak 10 insights in hearing health technology. Seminars in Hearing. 2020;41:37-54.

- Bisgaard N, Ruf S. Findings from EuroTrak surveys from 2009 to 2015: Hearing loss prevalence, hearing aid adoption, and benefits of hearing aid use. American Journal of Audiology. 2017;26(3S):451-461.

- Keidser G, Dillon H, Flax M, Ching T, Brewer S. The NAL-NL2 prescription procedure. Audiology Research. 2011;1(1):e24.

- Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Intl. Journal of Human–Computer Interaction. 2008;24(6):574-594.