Survey reveals dispensing professionals’ attitudes about product benefits

A willingness-to-charge survey is used to gauge clinicians’ perceived value of four advanced features found in middle and upper-end hearing aid technology. Due to the fact that many patients are reluctant to purchase hearing aids and therefore rely on the expert opinion of trained professionals to make a buying decision, willingness-to-charge data provides useful clinical and business insights.

|

| Brian Taylor, AuD, is director of the Professional Development Department at Amplifon USA, Plymouth, Minn. |

It is the patient and their willingness to pay for your products and services that makes your practice successful.1 From an economic perspective, this focus on the patient and what they are willing to pay is what largely determines your economic value as a professional.

One of the unique challenges for the hearing care field relates to the fact that many people with hearing impairment are simply unwilling to purchase hearing aids. These people largely rely on the advice of the hearing care professional to help move them to ownership of their problem, and to ultimately make a buying decision.

This reality, coupled with the fact that hearing aids are a highly technical “medical device,” places more focus on what the professional is willing to charge rather than on what the patient is willing to pay. The focus of this paper is to shed light on the value of collecting and analyzing willingness-to-charge data from hearing care professionals.

Willingness-to-charge data may help hearing aid manufacturers gain a better understanding of how dispensing professionals in the field articulate the value of various advanced features to the end user. Additionally, clinicians and managers of dispensing businesses may learn how to more effectively articulate the value of certain features without overselling or underselling by looking at how much dispensing professionals are willing to charge for various advanced features.

There is an emerging body of evidence from outside the hearing aid industry2 suggesting that, when a group of experts are polled about a particular economic question, their collective wisdom can accurately shape business decisions. This principle can be applied to the economics of the retail hearing aid dispensing business.

Putting a Price on Hearing

In the hearing industry there have been some studies that have focused on a patient’s willingness to pay for products and services. Palmer et al.3 examined patients’ willingness to pay for hearing aids with different sound quality. The authors found a strong relationship between the perceived sound quality of the hearing aid and the amount of money patients were willing to pay for hearing aids associated with that sound quality. Using a procedure in which participants were asked to provide dollar value judgments on aided sound quality, results suggested that participants were willing to pay upwards of $200 extra dollars for a hearing aid with a Class D amplifier over one with Class A. Another study published some 6 years later was consistent with these results, essentially indicating that patients are willing to pay extra for improved sound quality.4 Both of these studies examined willingness to pay in terms of post-fitting benefit.

In an attempt to look at willingness to pay before the selection and fitting of hearing aids occurred, Abrams et al.5 conducted a study in which both experienced and new hearing aid users were educated on the various benefits of four advanced hearing aid features. Once each group was educated on these potential benefits, they were asked to rate the dollar value of each feature. These results are shown in Table 1 (below). Participants with no hearing aid experience placed a higher overall value rating on the four features surveyed than the experienced group of hearing aid users.

|

Experienced Feature |

Inexperienced User |

User |

|

Feedback Reduction |

$318.42 |

$319.49 |

|

Directional Mic |

$265.82 |

$332.57 |

|

Expansion |

$241.94 |

$326.76 |

|

Noise Management |

$176.01 |

$241.09 |

|

TABLE 1. Mean willingness-to-pay values reported by patients in Abrams et al. (2004).5 Reprinted with permission. |

||

What patients are willing to pay, however, does not necessarily equate to what professionals are willing to charge for these advanced features. It is been reported elsewhere6 that hearing care professionals, especially audiologists, have an aversion to the “selling process.” If there is a gap between what a patient is willing to pay and what the professional is willing to charge, it may produce two results:

1) Over valuing. Some professionals may be inflating the retail value of certain advanced hearing aid features. A significantly higher-than-average perception of value could be a sign that professionals focus too much on marketing hype and not enough on what the clinical evidence supports. This could lead to returns for credit, low usage rates by patients, and overall dissatisfaction with amplification.

2) Devaluing. Other professionals might be willing to charge significantly less-than-average prices for these same advanced hearing aid features. This might reflect a discomfort on the part of the professional to simply ask for the business. This could lead to many patients walking out the door without being helped or over-discounting, which is inefficient for any business.

In either case, these would indicate opportunities to educate professionals on how evidence of real-world effectiveness needs to be considered when selecting hearing aids, or how some professionals need to become more comfortable with the “sales” aspect of the profession.

Willing-to-Charge Survey

The purpose of this survey was to more closely examine what a group of experienced audiologists and hearing instrument specialists would be willing to charge for four advanced features found in modern hearing aids: Automatic/Adaptive Directional Microphones, Digital Noise Reduction, Automatic Feedback Cancellation, and Datalogging. These features were selected because they are commonly found in most modern hearing aids at the middle- and higher-end retail price points, and they are typically adjusted or fine-tuned by the dispensing professional.

The following question was asked of 45 (27 hearing instrument specialists and 18 audiologists) experienced hearing care professionals: “Given a baseline retail price of $1000 for a digital multiple-channel WDRC instrument, how much are you willing to charge the typical patient for the following four advanced hearing aid features: Automatic/Adaptive Directional Microphones, Digital Noise Reduction, Automatic Feedback Cancellation, and Datalogging.” Respondents were required to record their answers in $25 increments, and to assume that the patient’s communication needs and audiometric results would warrant the recommendation of these advanced features. (Author’s note: Willingness to pay studies,3-4 when corrected for inflation, approximate a $1000 per unit value, and would be considered a universal starting point for restoring soft speech sounds.)

Unlike the Abrams et al.,4,5 willingness-to-pay studies, expansion was not included as one of the features. This is due to the fact that expansion is found on virtually all of today’s digital products, even entry-level models. In addition, expansion is often a feature that cannot be adjusted like the other advanced features in this survey.

The professional experience of the 45 respondents ranged from 2 years to over 20 years. All respondents practiced in Sonus locations around the United States. The question posed above was asked before any formal instruction on product features and benefits was conducted in order to account for any training effects. Each respondent independently answered the question, and was not allowed to discuss with the other respondents how they would answer the question.

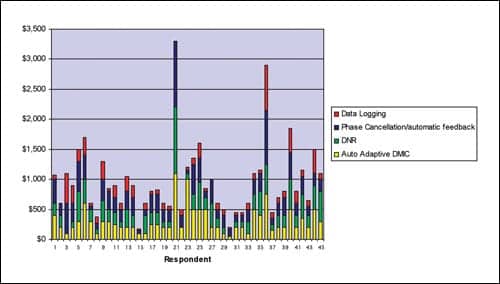

|

| FIGURE 1. Perceived dollar value of four advanced hearing aid features for 45 respondents. |

Results and Discussion

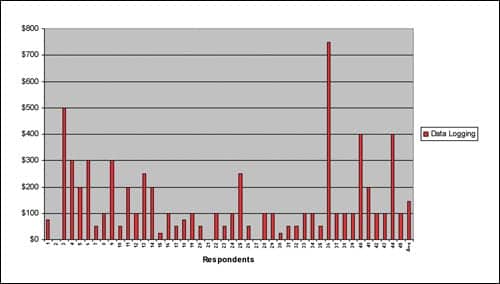

Figure 1 above shows the willingness-to-charge range of answers from the 45 respondents. Each of the four advanced features is depicted in a separate color on the bar graph. The most striking observation is that there is tremendous variation across the 45 respondents concerning how much they are willing to charge patients for these four common advanced features. For example, Respondents #15 and #30 felt comfortable charging less than $250 for all these features combined, whereas Respondents #21 and #36 were willing to charge well over $2500 for the same four advanced features.

This sizeable gap in what professionals are willing to charge is striking and warrants further explanation. Perhaps some of the respondents did not fully understand the question and were not able to answer it effectively. Although a plausible explanation, it is unlikely due to the fact that all of the respondents have a minimum of 2 years of hearing aid dispensing experience and had received product training.

A better explanation is related to the fact that hearing care professionals collectively do not have a systematic understanding of how these advanced features can benefit their patients in everyday listening situations. In other words, some professionals have difficulty articulating the dollar value of these advanced features.

A closer examination of the data in Figure 1 indicates that, not only is there tremendous variation across professionals in their willingness to charge, but there is also substantial variation between features. That is, there is no clear consensus across professionals that any one of the four advanced features is valued higher than any other. This lack of consensus may suggest that many dispensing professionals find it challenging to clearly articulate the real-world value of these features.

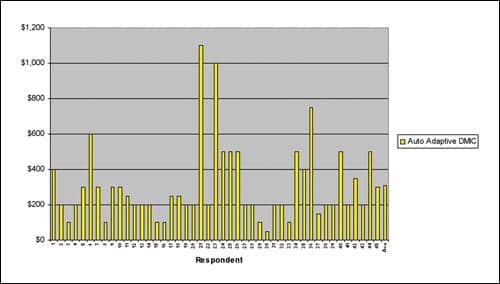

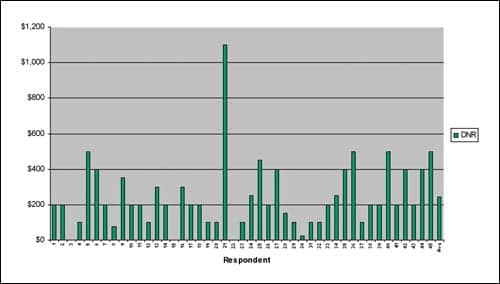

A more careful look at the variation in willingness to charge is necessary. Automatic/advanced directional microphones (AADM) and digital noise reduction (DNR) are two commonly used features on advanced hearing aids. Both features have been on the market for years. Both features have some, albeit limited, real-world evidence supporting their effectiveness.7 In view of the laboratory and real-world evidence supporting their effectiveness, it would seem logical that the majority of professionals would have a clear understanding of how this translates into retail value.

Figures 2 and 3 show the willingness-to-charge range across the 45 respondents for AADM and DNR. For the AADM feature, the willingness-to-charge range is $25 to $1100 with a mean of $308. For DNR, the willingness-to-charge range is $0 to $1100 with a mean of $243. (It is noteworthy that the high end of both ranges [$1100] was submitted by the same respondent, and when this response is thrown out the range is substantially less for both features.)

|

| FIGURE 2. Willingness-to-charge values from 45 respondents for the automatic/adaptive directional microphone feature. |

|

| FIGURE 3. Willingness-to-charge values from 45 respondents for the digital noise reduction feature. |

Given the definitive laboratory and real-world evidence supporting the benefits of directional microphone technology,8 it is somewhat surprising that the AADM feature was not rated with a higher dollar value. This might be indicative of some of the limitations dispensing professionals encounter on a daily basis when trying to improve speech intelligibility in noise using directional microphones. Even though both features have widespread use, along with fairly good evidence to support their effectiveness in everyday listening situations, there is not a consensus amongst professionals relative to retail value for end users.

Two other advanced features were part of the survey: automatic feedback control (AFC) and datalogging. To date, there is scant direct evidence supporting the effectiveness of AFC and datalogging in everyday listening situations and the ability of these features to increase customer satisfaction and/or enhance listening ability. However, virtually all hearing aid manufacturers have touted the quality of their AFC. Figure 4 shows a willingness to charge range of $0 to $1100 with a mean value of $277, which is higher than the mean for DNR. Even though the evidence is thin, professionals (on average) clearly see the value to the end user of AFC.

|

| FIGURE 4. Willingness to charge values for AFC from 45 respondents. |

Datalogging is the most recent advance feature to be found in many higher end hearing instruments. Although there is variation between manufacturers on exactly how datalogging operates, it is widely accepted that datalogging objectively monitors hearing aid use rate. There is some evidence to support greater use rates reflect higher overall satisfaction rates.9 Although there is little hard evidence (ie, as with AADM) to support its effectiveness, datalogging has become a popular feature and can be found in many of the manufacturer’s new mid- and upper-end products. Figure 5 shows how this might relate to the professional’s perception of the value of datalogging. There is a willingness-to-charge range of $0 to $750 with a mean score of $144. It is of interest that 13 (almost one-third) of the 45 respondents rated datalogging to be $50 or less. Of the four advanced features surveyed, datalogging has the lowest mean score by a margin of nearly $100.

|

| FIGURE 5. Willingness-to-charge values for datalogging from 45 respondents. |

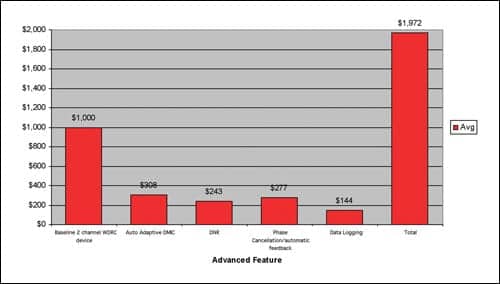

It has been demonstrated elsewhere that a diversity of opinion, reflected in a wide range of responses like the ones presented here, can help answer economic questions.2 Collective wisdom, as it is commonly called, might actually help more clearly define what the “best” retail price might be. Figure 6 shows the mean willingness-to-charge values for the four advanced features. These mean values reflect the collective wisdom of a group of experienced practitioners, and provide important insights on retail value. They might serve as a benchmark for establishing the retail value of hearing aids offering these advanced features. Indeed, the final value of $1972 is close (within 3%) to the $2022 average price of a digital hearing aid reported in The Hearing Review 2006 Dispenser Survey.10

|

| FIGURE 6. Mean willingness-to-charge values for four advanced features. The total of $1,972 is derived from adding the baseline value of $1,000 to the four mean values. |

Clinical Implications

Several clinically relevant points can be gleaned from this survey.

1. The mean willingness-to-charge value for each feature represents a benchmark figure for professionals, and these willingness-to-charge averages should be considered when determining retail prices for hearing aids. If dispensing professionals believe that the prices they are charging are worth the money to their patients, they are more likely to be successful from a business standpoint.

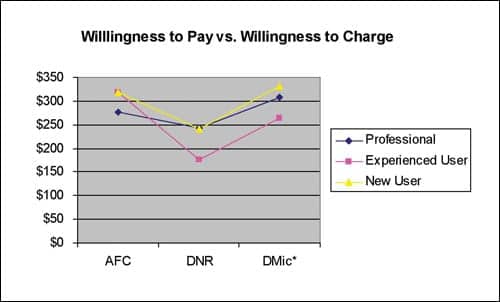

2. The mean willingness-to-pay data can be compared to the mean willingness-to-charge data5 for three of the features (Figure 7). When compared to inexperienced hearing aid users, dispensing professionals are willing to charge less than what patients are willing to pay. From a business perspective this suggests that professionals are not charging enough for some products.

|

| FIGURE 7. A comparison of willingness-to-charge survey data in the present study to the willingness-to-pay data in the Abrams et al.5 study. The asterisk (*) denotes that Dmic in Abrams et al. was fixed rather than automatic/adaptive. |

When compared to experienced hearing aid users, professionals are generally willing to charge more than what these patients are willing to pay. This suggests a tendency to oversell advanced features to this user group. Based on the data, professionals (in general) would be advised to find ways to add more value to their products, especially when working with experienced users.

3. Professionals who are willing to charge significantly more than the mean should be cautious about overselling without sufficient evidence to support their recommendation. These professionals may be prone to relying too heavily on manufacturers product claims, many of which are not supported by real-world evidence. According to the data in Figure 1, approximately one-third of the respondents were above the mean, and possibly at-risk for overselling.

4. The majority of respondents’ mean scores fell below the mean value, suggesting that these professionals might be devaluing the benefits of these advanced features. These professionals should be targeted for additional consultative sales training. It’s entirely possible that they simply lack the language to clearly articulate the value of higher end advanced features.

5. When new features are introduced to the market, manufacturers and clinicians alike would be wise to survey their groups to find the mean willingness-to-charge retail price of that feature.

6. It should be noted that willingness-to-charge data for services was not part of this study. Using a similar approach both patients and professionals could be surveyed to find the mean value of warranties, as well as loss & damage protection, etc. Although not specifically mentioned, it is probable that respondents bundled services along with product when completing this survey.

This survey shows how willingness-to-charge data can be used to gauge the perceived value of four advanced features found in middle and upper-end hearing aid technology. Due to the fact that many patients are reluctant to purchase hearing aids—and therefore rely on the expert opinion of trained professionals to make a buying decision—this willingness-to-charge data provides useful clinical and business insights.

The data presented here, among other things, suggests that evidence-based audiology—evidence that supports activities relating to patient satisfaction for driving clinical practice—is an area that needs greater attention. Additionally, willingness-to-charge data identifies areas of concern, like overselling and underselling, that warrant further training.

References

- Drucker P. Management Challenges of the 21st Century. New York City: Harper Business; 2000.

- Surowiecki J. The Wisdom of Crowds. New York City: Doubleday Press; 2004.

- Palmer C, Killion M, Wilber L, Ballard W. Comparison of two hearing aid receiver-amplifier combinations using sound quality judgments. Ear Hear. 1995; 16(6):587-598.

- Chisolm T, Abrams H. Measuring hearing aid benefit using a willingness-to-pay approach. J Am Acad Audiol. 2001; 12:383-389.

- Abrams H, Block M, Hnath Chisolm T. The effects of signal processing and style on perceived value of hearing aids. The Hearing Review. 2004; 11(13):16-21,70.

- Riggs K. “Selling” in the professional setting. The Hearing Review. 2006; 13(2):56-59.

- Bentler R. Effectiveness of directional microphones and digital noise reduction schemes in hearing aids: A systematic review of the evidence. J Am Acad Audiol. 2005;16(7):473-484.

- Ricketts T. Directional microphones; then and now. J Rehab Res Dev. 2005;42(4):133-144.

- Wong, L. Hearing aid satisfaction: What does research from the past 20 years say? Trends in Amplif. 2003;7(4):117-161.

- Strom KE. The HR 2006 dispenser survey. The Hearing Review. 2006; 13(6):16-39.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Brian Taylor, Amplifon USA, 5000 Cheshire Lane, Plymouth, MN 55446; e-mail: .