Summary:

A new study co-led by Indiana University School of Medicine researchers has identified how electrical charges in the inner ear trigger TMPRSS3-related hearing loss—and found that a common drug, Lasix, may help prevent it before deafness occurs.

Key Takeaways:

- TMPRSS3 is one of the most common genes linked to genetic hearing loss, especially in young adults requiring cochlear implants.

- Researchers discovered that normal inner ear electrical activity (endocochlear potential) can damage hair cells in those with TMPRSS3 mutations.

- Administering Lasix reduced this damage in mice, suggesting a potential preventive treatment before irreversible hearing loss develops.

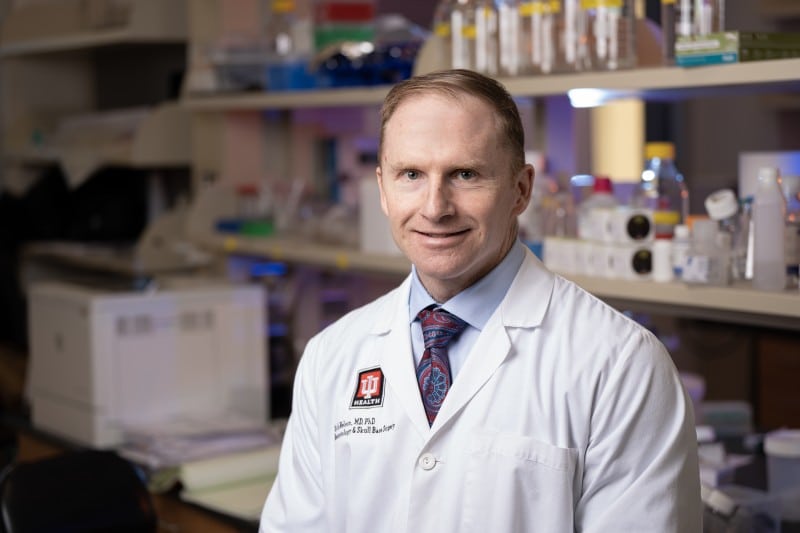

A research team co-led by an Indiana University School of Medicine physician scientist has pinpointed how electrical charges within the ear contribute to a common type of genetic hearing loss, opening up possibilities for intervention before deafness occurs.

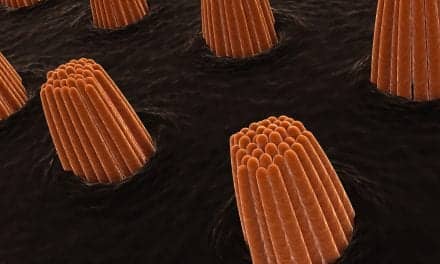

These findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, centered around the gene TMPRSS3, which is the most common gene identified in young adults undergoing cochlear implantation—a surgical procedure in which an electronic hearing device is installed above the ear. The new study found that endocochlear potential, a normal process which essentially switches on hearing, damages critical hair cells in mice with the gene.

“Think of endocochlear potential as the ‘battery charge’ of the inner ear,” said Rick Nelson, PhD, MD, co-lead author of the study and professor of neurosurgery and otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the IU School of Medicine. “The potential is generated prior to a person’s ability to hear. If there is no endocochlear potential, then there is no hearing.”

Researchers were able to protect the hair cells by administering Lasix, a diuretic known to decrease endocochlear potential. They hope to stop TMPRSS3 hearing loss before it starts, as patients currently rely on hearing aids and cochlear implants to treat damage after the fact.

“The goal is to understand the mechanism of TMPRSS3 hearing loss and then generate treatments to prevent hearing loss,” Nelson said. “It is important to treat patients prior to hearing loss because if the hair cells die, then we currently cannot regenerate hair cells to restore hearing.”

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, approximately 1 in 1,000 infants are born with a hearing deficiency due to genetics, with the TMPRSS3 gene among the top five most common.

Some people with the TMPRSS3 gene are born deaf, while others begin to experience high-frequency hearing loss as a child or teenager.

Inner ear hair cell regeneration after hair cell damage does not occur in humans or mice. Studies are ongoing to regenerate hair cells, Nelson said, but currently it is not possible to regain hearing through regeneration.

Endocochlear potential, when it occurs at a normal voltage, is an essential part of the ear’s function. So, one challenge is not to limit it entirely.

Nelson said he hopes to continue studying how endocochlear potential affects ear hair loss, the treatment angle discovered in the study and possible gene therapies to combat TMPRSS3 hearing loss.

The study was a collaboration between IU School of Medicine and Harvard University researchers, as well as researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Other IU School of Medicine co-authors included Yuan-Siao Chen, Kevin T.A. Booth, Jinan Li, Jing-Yu Lei, Ernesto Cabrera, Douglas J. Totten, Bo Zhao, Jasmine Moawad and Nicole Bianca Libiran.

The research was supported by a variety of grants, including several from the National institutes of Health and a biomedical research grant from IU.

Featured image: Researcher Rick Nelson, PhD, MD, of Indiana University School of Medicine. Photo: Tim Yates, IU School of Medicine