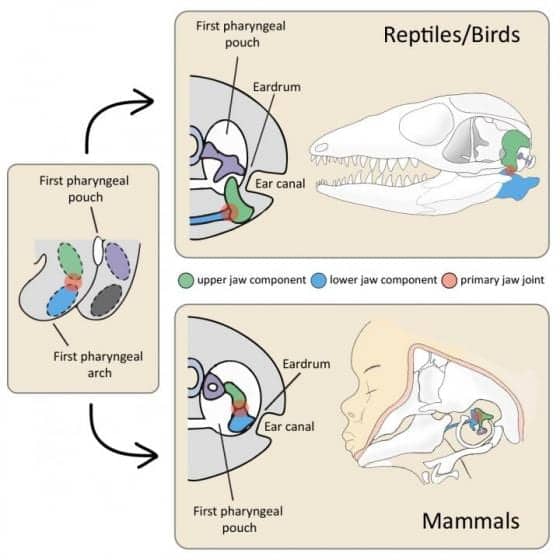

According to a recent announcement, Japanese researchers at the RIKEN Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory and the University of Tokyo have determined that the middle ear and eardrum evolved independently in mammals and reptiles or birds (diapsids). As outlined in an article published in the April 22, 2015 edition of Nature Communications, the researchers discovered that the mammalian eardrum depends on lower jaw formation, while the eardrum of reptiles or birds depends on upper jaw formation. The researchers reportedly used developmental biology techniques to make these discoveries about the evolution of the eardrum, answering questions that have long mystified paleontologists.

The study authors report that the evolution of the eardrum and the middle ear is what has allowed mammals, reptiles, and birds to hear through the air. Their eardrums all look and function similarly. However, according to the researchers, the fossil record shows that the middle ears in these two lineages are fundamentally different, with two of the bones that make up the mammalian middle ear—the hammer and the anvil—being homologous with parts of diapsid jawbones—the articular and quadrate. In both lineages, these bones connect at the primary jaw joint.

Although scientists have suspected that the eardrum and hearing developed independently in mammals and diapsids, the eardrum is never fossilized so no hard evidence has been found in the fossil record.

To overcome this challenge, the research team relied on evolutionary developmental biology. They hypothesized that eardrum evolution was related to different upper and lower jawbones, and performed a series of experiments that manipulated lower jaw development in mice and chickens. Their work revealed that in mammals, the eardrum attaches to the tympanic ring—of the lower jawbone—while in diapsids it attaches to the quadrate—of the upper jawbone.

While scientists still do not know how or why the primary jaw junction shifted upwards in mammals, the study shows that the middle ear developed after this shift and must have occurred independently after mammal and diapsid lineages diverged from their common ancestor.

“This approach to studying middle ear evolution could help us understand other related evolutionary changes in mammals, including the ability to detect higher toned sounds and even our greater metabolic efficiency,” said lead study author Masaki Takechi, PhD, Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory, RIKEN.

For more on the evolution of hearing, see the February 14, 2015 article in The Hearing Review.

Source: Nature Communications, RIKEN Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory, University of Tokyo

Image credit: RIKEN Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory

Article citation: Kitazawa T, Takechi M, Hirasawa T, Adachi N, Narboux-Neme N, Kume H, Maeda K, Hirai T, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Kurihara Y, Hitomi J, Levi G, Kuratani S, and Kurihara H. (2015) Developmental Genetic Bases behind the Independent Origin of the Tympanic Membrane in Mammals and Diapsids. Nature Communications. Doi:10.1038/ncomms7853.