Researchers from the University of Iowa and Newcastle University have taken advantage of a rare opportunity to record and map tinnitus in the brain of a patient undergoing surgery, with the goal of finding the brain networks responsible for this condition characterized by “phantom noise.” According to an April 23, 2015 article published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology, their findings reveal the differences between tinnitus and normal representations of sounds in the brain.

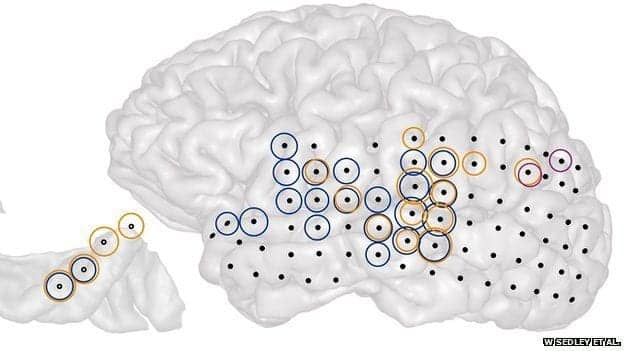

“Perhaps the most remarkable finding was that activity directly linked to tinnitus was very extensive, and spanned a large proportion of the part of the brain we measured from,” said William Sedley, PhD, of Newcastle University. “In contrast, the brain responses to a sound we played that mimicked [the subject’s] tinnitus were localized to just a tiny area.”

A 3-D image of the brain’s left hemisphere in a patient with tinnitus. At left is the part of that hemisphere containing the primary auditory cortex. The colored circles indicate where the strength of different rhythms of brain activity correlated with the strength of the patient’s tinnitus.

For this study involving a single patient, Sedley and collaborator Phillip E. Gander, PhD, from University of Iowa, examined the patient’s brain activity during periods when tinnitus was relatively stronger and weaker. The researchers report that the study was possible because the 50-year-old patient involved required invasive electrode monitoring for epilepsy, and also happened to have a typical pattern of tinnitus, including ringing in both ears, in association with hearing loss. Gander explained that it is rare that a person requiring invasive electrode monitoring for epilepsy also has tinnitus.

As outlined in their article, the researchers found the expected tinnitus-linked brain activity, but report that this activity extended far beyond circumscribed auditory cortical regions to encompass almost all of the auditory cortex, along with other parts of the brain. They say this discovery adds to our understanding of tinnitus and helps to explain why treatment of tinnitus has been so challenging.

“We now know that tinnitus is represented very differently in the brain to normal sounds, even ones that sound the same, and therefore these cannot necessarily be used as the basis for understanding tinnitus or targeting treatment,” said the researchers. “The sheer amount of the brain across which the tinnitus network is present suggests that tinnitus may not simply ‘fill in the gap’ left by hearing damage, but also actively infiltrates beyond this into wider brain systems.”

According to the researchers, their discoveries may help to inform treatments such as neurofeedback or electromagnetic brain stimulation, and that a better understanding of the brain patterns associated with tinnitus may also help inform new pharmacological approaches to treatment.

Source: Cell Press, Current Biology, Newcastle University, BBC News

Image credits: W. Sedley et al, Newcastle University