Researchers supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are launching a clinical trial to test a device that uses nervous system stimuli to rewire parts of the brain, in hopes of significantly reducing or removing tinnitus, a persistent buzzing or ringing sound in the ears in the absence of any real sound.

The small clinical trial, which is recruiting volunteers, is being conducted at four centers through a cooperative agreement with MicroTransponder, Inc, a medical device company based in Dallas.

Roughly 10% of the adult population of the US has experienced tinnitus lasting at least 5 minutes in the past year, and approximately 10 million of them have been bothered enough by the condition to see a doctor. Although tinnitus may be only an annoyance for some, for others the relentless ringing causes fatigue, depression, anxiety, and problems with memory and concentration. Available treatments help some people cope, but current therapies lack the potential to significantly reduce the bothersome symptoms of tinnitus.

The trial, supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), a part of NIH, may mark the beginning of a change in how tinnitus is treated.

“Tinnitus affects nearly 24 million adult Americans,” says James F. Battey, Jr, MD, PhD, director of the NIDCD. “It is also the number one service-connected disability for returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. The kind of nervous system stimuli used in this study has already been shown to safely and effectively help people with epilepsy [and] depression. This therapy could offer a profoundly better way to treat tinnitus.”

Most cases of chronic tinnitus are preceded by a loss of hearing as the result of damage to the inner ear from aging, injury, or long-term exposure to loud noise. When sensory cells in the inner ear are damaged, the resulting hearing loss changes some of the signals sent from the ear to neurons in the auditory cortex of the brain. Scientists still haven’t agreed upon what happens to create the illusion of sound when there is none, but the therapy being tested in this new clinical trial attempts to ameliorate the phantom sound of tinnitus by going to its source—the brain.

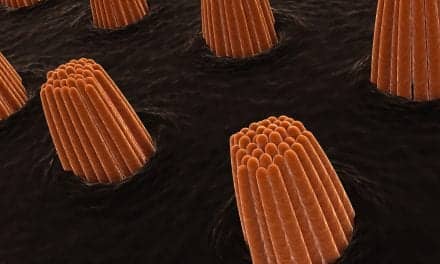

The auditory pathway is organized by what scientists call the tonotopic map, a structural arrangement in which different tone frequencies are transmitted separately along specific parts of the pathway. Hearing loss is the result of a loss in the ability of the auditory system to process certain frequencies. Earlier studies showed that the loss of the ability to hear these frequencies matched patterns of distortion in the neurons of the auditory cortex’s tonotopic map.

This research suggests that tinnitus might be the result of the brain trying to regain the ability to hear those lost frequencies by turning up the signals of neurons in neighboring frequencies. Because there are too many neurons processing the same frequencies, they fire more strongly, more frequently and in concert with each other, even when the environment is quiet. It is these changing brain patterns that researchers believe could produce the perception of whooshing, ringing, or buzzing in the ear that characterizes tinnitus.

The new study uses a technique known as vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) that takes advantage of the brain’s ability to reconfigure itself (neuroplasticity). During the therapy, patients wear headphones and hear a series of single frequency tones, paired with stimulation to the vagus nerve, a large nerve that runs from the head and neck to the abdomen. When stimulated, the vagus nerve releases acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and other chemicals that encourage neuroplasticity.

In an earlier NIDCD-funded study using a rat model, the technique was shown to reorganize neurons to respond to their original frequencies, subdue their activity, and reduce their synchronous firing, suggesting that the ringing sensation had stopped. The scientists subsequently tested a prototype device in a small group of human volunteers in Europe and observed encouraging results.

For this new study, two groups of adults who have had moderate-to-severe tinnitus for at least one year will participate in daily two and a half hour sessions of VNS and audio tone therapy over six weeks. One group will get the VNS and tone test treatment immediately; the other will get a combination of VNS and tones that is not expected to have a therapeutic benefit. After six weeks, both groups will receive active test treatment.

Outcomes will be measured throughout the year-long trial using the Tinnitus Functional Index and the Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire, two questionnaires that allow patients to report on the extent of their tinnitus. They will also be tested periodically to determine changes in minimum masking levels for the tinnitus—the decibel level of sound required to eliminate awareness of the tinnitus.

“This trial has the potential to open up a whole new world of tinnitus management,” says Gordon Hughes, MD, director of clinical trials at the NIDCD. “Currently, we usually offer patients a hearing aid if they have hearing loss or a masking device if they don’t. None of these treatments cures tinnitus. But this new treatment offers the possibility of reducing or eliminating the bothersome perception of tinnitus in some patients.”

The clinical trial sites are at the University of Texas at Dallas; University of Buffalo (SUNY), Buffalo; and the University of Iowa, Iowa City. An additional site will be added later in the year. More information about the trial and enrollment is available on the study’s website or at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01962558).

“The support of the NIDCD has been essential to bringing this novel tinnitus therapy into the clinic,” says MicroTransponder CEO Frank McEachern. “The translation of scientific discovery into medical therapies is a long and difficult path. The NIH recognized the importance of our tinnitus research early on, which enabled us to secure additional private funding for the extensive development effort required to build a device for clinical trials.”

The research is supported by NIDCD grant U44DC010084. Additional support for the University of Texas at Dallas research is provided by the Texas Biomedical Device Center.

Source: NIH