By Adrienne rubinstein, PhD; Rochelle Cherry, EdD; and Elvera BAder, BS

How can we change attitudes about hearing conservation in university music programs?

Recent studies have shown evidence of a decrease in hearing ability among youth, and although the amount of change is a subject of debate,1-3 these findings have led to greater interest on this topic in the research literature, as well as the popular media.4 Implicated as a contributing factor is the high level exposure to music in various entertainment venues5 and through personal listening devices.4,6 Reviewing the literature, Zhao et al7 concluded that many people are often exposed to music levels that far exceed acceptable noise exposure limits, both recreationally and professionally.

The risk of music-induced hearing loss is especially a concern for students in music programs.8 In addition to their leisure-time music exposure, they are subject to exposure during rehearsals, personal practice, and performances. Furthermore, their future livelihood depends on a particularly intact auditory system.

Growing evidence in the literature lends support to the concern that music students may be at greater risk.10-12 Phillips and Mace,12 for example, estimated the exposure dose of 40 music students based on the mean duration of daily practice according to student reports and measured sound levels; they found that 48% of the students were exposed to levels exceeding the allowable dose from a single average session in a practice room. Furthermore, Phillips et al13 found that, of 329 college student musicians, 45% demonstrated a hearing loss typical of music-induced hearing loss. In addition to hearing loss, other high level sound exposure effects (ie, tinnitus, hyperacusis, diplacusis) can interfere significantly with the musician’s ability to perform.14

There is increased recognition in music programs to consider health education in general and hearing prevention training in particular.15-17 The Health Promotion in Schools of Music (HPSM) project recommended monitoring of hearing for all students entering music programs, as well as increasing their knowledge of music-induced hearing loss and its prevention. In 2012, Callahan et al18 published survey data collected before and following a 50-minute educational presentation designed to raise awareness in college music students through collaboration between music and audiology departments. The presentation by an audiologist addressed topics such as characteristics and risk factors associated with sound-induced hearing loss and methods for reducing risk of hearing loss. Results revealed that student responses reflected greater knowledge in the postseminar survey and a perceived greater likelihood to use hearing protection devices and have their hearing tested in the future.

One factor that should be considered is the attitude of college music program faculty toward hearing health risk and ear protection use because they serve as role models, and their attitudes and behaviors can affect those of their students. Although this group has not been directly investigated, research studying symphony orchestra musicians revealed low use of personal hearing protectors.19,20

Laitinen and Poulsen,19 for example, found that musicians at three Danish symphony orchestras rarely used ear protection. They reported that 84% never wear ear protection at personal rehearsals and 94% never wear them while teaching. About 4 in 5 (79%) rarely, if ever, wear it during performances, and 70% rarely, if ever, wear it at orchestra rehearsals. They also explored the reasons among professional orchestral musicians regarding their objections to ear protection use. Their results indicated that some musicians found it harder to control their playing, some had difficulty with earplug fit, and others simply were not concerned about their hearing.

In addition to their attitudes regarding hearing health risk and their use of personal ear protection, it is particularly important to know whether college music faculty are supportive of a hearing loss prevention program and, if so, their views regarding the form it should take. Their attitudes could significantly impact program success through their input in the choice of program content and the style of presentation.

|

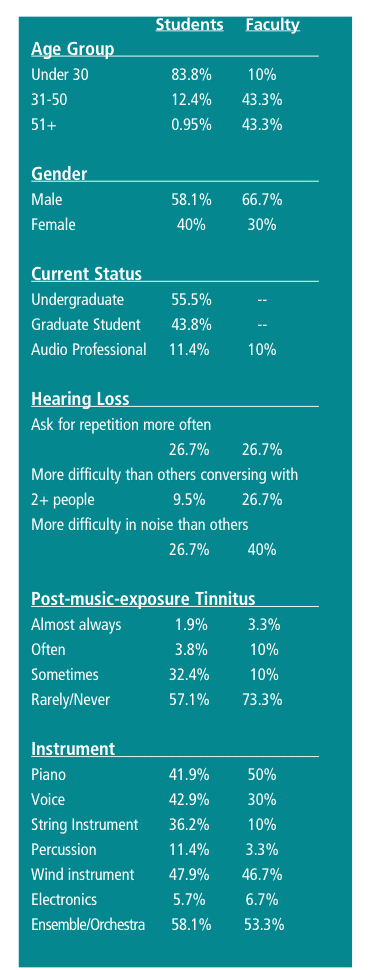

| Table 1. Percentage of participants responding to demographic questions. |

The present study was designed to determine the health beliefs and behaviors of college music faculty and students regarding the effects of music and other sounds on hearing and the use of various ear protection strategies. The second goal was to learn the attitudes of college music faculty and students regarding training preferences in the education of students on the auditory system and hearing conservation, as well as desired services from the college.

Method

The survey used in this study was adapted from surveys that have been designed for similar purposes.18-21 It comprised 25 questions exploring the following topics: perceptions about the risk of loud music and other sounds to the auditory system (5), attitudes and behaviors related to auditory conservation strategies (4), and views regarding desired services and instruction from the college (5). Basic demographic information also was collected including items on age, gender, musical instruments played and professional activities (7), as well as perceived problems with hearing and tinnitus (2). The final question provided an opportunity for comments.

Participants were recruited from among faculty and students affiliated with the Conservatory of Music at Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, NY. Informed consent was obtained according to the approved Brooklyn College IRB protocol. Faculty members were recruited via e-mail from the Chair followed by an announcement by the investigators at a faculty meeting, Access to the survey was available online or by hard copy. Students learned about the study from announcements made in classes designed for music majors after which they were given the opportunity to fill out the survey. Additionally, on three random occasions, on their way to or from classes, students were invited to take the survey or take a copy with them to fill out at their convenience and return it to the music program office.

Results

Of the 71 faculty affiliated with the Conservatory of Music, 30 responded to the survey (42% response rate). Of a potential pool of 263 undergraduate majors and graduate students, 105 filled out the survey (40% response rate). Table 1 summarizes the demographic data.

In the summary of results below, data are reported separately for faculty and students unless results were essentially the same, in which case the groups were averaged together. In the online version of this article (www.hearingreview.com), the Appendix section contains the actual questions and the collated responses for both groups.

Knowledge of Risk of Loud Music and Other Sounds to the Ear

Results revealed that neither music faculty nor students are sufficiently informed about the types and conditions of risky sound exposure. Over a quarter of the students and 13% of faculty reported that they had never even been told of such a risk (Question 2). Both groups were more aware of the risks of nonmusic-related recreational exposure than music-related (Question 4); a greater percentage of both groups acknowledged the potential risk of recreational noise exposure (such as the sounds from motorboats (69%) and spectator sporting events (64%)) than the possibility that a single instrument, such as a piccolo (44%) or violin (18%), could reach dangerous levels to hearing.

In addition, 35% of the participants were unaware that permanent hearing loss can occur from a single insult (Question 5). When questioned about the sound level that is associated with danger to human hearing, only 30% of the faculty and 19% of the students responded correctly (85 dBA), with the majority responding inaccurately to 95 dBA or greater (Question 6).

Attitudes and Behaviors Regarding Ear Protection

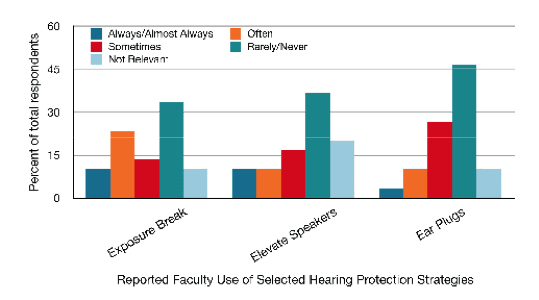

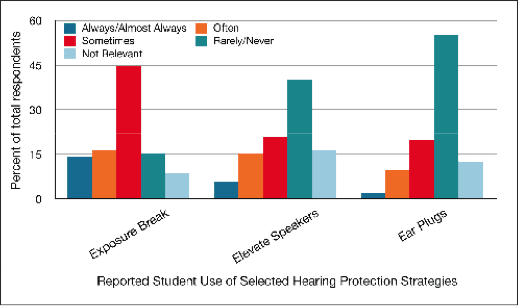

Although most faculty and students on average acknowledged that hearing could be protected (81%) and tinnitus could be prevented (70%) (Question 8), neither group reported using hearing protection strategies often if ever (Question 9). Figures 1a and 1b summarize the results for the strategies used most often for faculty and students, respectively. Only 12% of the respondents reported using earplugs “always” or “ often,” with 47% of the faculty and 55% of the students reporting their usage as “rarely or never.”

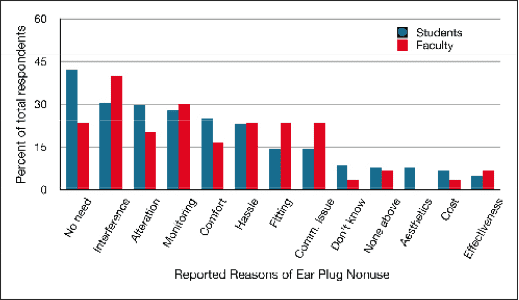

Figure 2 summarizes the results from those who were less inclined to use earplugs and gave their reasons for nonuse (Questions 10). The most popular reason for rejection cited by faculty related to the difficulty hearing other environmental sounds (40%), followed by problems monitoring the music (30%). For students, the most-common response was their perception that ear plugs were not needed (42%), followed by problems hearing other environmental sounds (30%).

It should be noted that 23% of the faculty reported that earplugs were not needed. When asked when they last had their hearing tested (Question 7), 13% of the respondents reported having had their hearing tested within the past year, and 29% of the respondents reported that their hearing had not been tested within 1 to 3+ years with the ranking similar for both groups.

Views Regarding a College Hearing Conservation Program

A critical question addressed in the survey was whether faculty were in favor of hearing loss prevention instruction as part of a music course of study (Question 11). A majority in both groups replied affirmatively, with a higher percentage of faculty in favor (83% of faculty and 65% of students).

Question 12 probed the objections to such a program. In all, only three faculty members responded to this item, and each for a different reason. Of the 37 students who elucidated their concerns, the greatest percentage (62%) reported that there were too many other areas to be covered in the music program. The survey also asked about preferred topics of faculty and students to be included in a hearing conservation program. The response with the greatest percentage was the same for both faculty and students: hearing/ear protection strategies (faculty 80%; students 62%), followed by hearing loss and other abnormalities associated with sound-induced hearing loss (faculty 73%; students 59%).

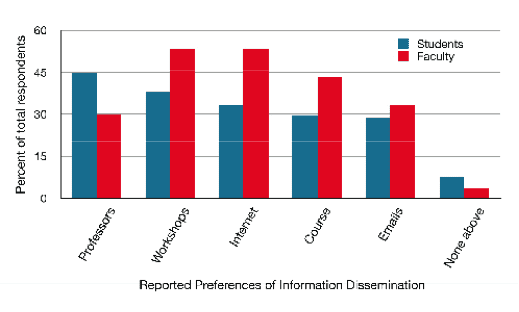

The respondents also were asked about their preferred methods of information dissemination. The data are summarized in Figure 3. Of the faculty, 53% ranked both periodic workshops and referral to relevant Internet websites as their first choices, followed by choosing part of a college course on performance health (43%). The greatest percentage of students chose periodic instruction by music professors (45%) followed by periodic workshops (38%) and referral to relevant websites (33%).

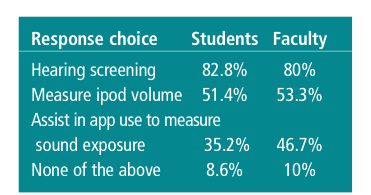

Table 2 summarizes the desired hearing conservation services: both groups enthusiastically chose freeannual hearing screening (82%), followed by measures of the sound volume of music from their iPods to determine if it is at a damaging level (52%).

|

| Table 2. Percentage of respondents who selected each of the self-rating choices in Question 15: “If offered by the college, I would be interested in (Check all that apply).” |

Discussion

The majority of music faculty endorsed some hearing loss prevention instruction as part of a music course of study, as did the students. One question raised is the optimal venue for such instruction. As noted earlier, Callahan et al18 provided a 50-minute presentation to music students relating to hearing loss, which was part of a required Music Convocation Series, and they noted that the HPSM project also recommends hearing conservation efforts as part of their regular ensemble-based instruction.

In the current study, we noted a discrepancy in the order of preferences in method of dissemination among faculty versus students. The venues with the highest response rate for faculty involved extracurricular activities or a special course on performance health outside of the current classes. Students, on the other hand, chose as their top preference periodic instruction by their music professors—implying a preference for incorporating it within their current coursework. This time concern of students also was reflected in response to the question regarding why students were not in favor of a hearing conservation program; 62% of students not in favor of hearing education expressed that there are too many other areas in the program that needed to be covered. This supports the need to build the material into the program, but in a way that is acceptable to the faculty as well.

Resistance to hearing protection. Although results revealed a high level of support from both groups for the concept of receiving information on hearing loss prevention, results also revealed that only a small percentage of faculty and students use ear protection strategies regularly. The ranking of reasons for low use of ear plugs was different for the two groups. The concern responded to most among faculty was the negative impact on the sound of the music as well as environmental sounds. This is similar to the findings from professional orchestral musicians.19,20 The most frequent reason cited for rejection by students was that they did not feel it was needed. This also is consistent with previous findings in this population.8,15 Thus, it appears that music faculty—although they may not be consistent users—are more aware of the need for protection. Clearly, however, the topic of interest chosen for a hearing conservation program by both groups was education about the different types of ear protection strategies.

Huttunen et al22 considered the possibility that one factor in rejection among professional musicians was due to poor earplug attenuation properties. However, using custom-molded musician’s earplugs (Etymotic Research ER-15) with symphony orchestra musicians, their results did not find a relationship between these two factors. They concluded that encouraging the musician to take the time to become accustomed to the device may be the more important factor.

Although audiologists still need to optimize the fit using verification of performance, musicians also may benefit from listening to themselves playing with versus without earplugs on a recording to adjust their technique and allay any concerns about the sound produced (Brian Fligor, personal communication, March 29, 2012). More research is needed to explore the relationship between appropriate management/follow-up and degree of satisfaction in dispensing of custom earplugs.

Although the faculty were less likely to negate the need to use hearing protection, it appears that both groups would benefit from more information regarding risks and benefits. Missing these important facts can limit the motivation to explore ear protection use and make an appropriate cost/benefit analysis.

In addition to the lack of knowledge reported earlier (eg, risk of music, maximum acceptable levels, etc) and the limited use of ear protection, the need for more information was reflected in the responses to the open-ended question at the end of the survey. Of the 13 faculty members who offered comments, five noted that their music exposure was not dangerous, often adding an example where they were aware of a problem (eg, iPods and amplified music). Classical musicians often fail to take into account the number of hours of music exposure as compared to musicians playing popular music14; they also may fail to consider the cumulative effects of additional sources of exposure, such as recreational music and public transportation. Such information may (at least) spur them to consider using hearing protection for purposes outside their music work and reduce their overall noise dose.

If faculty are better informed, they may become role models to their students on this issue. An important first step in any program may be to enlist the support of faculty by identifying their risk, and establishing whether a given individual is exposed to dangerous doses. Although measuring sound levels was the least likely strategy used by faculty or students, introducing this concept of measuring sound exposure level into the music program has tremendous potential to inform both groups about their actual risk of exposure.

Personal sound level monitoring. There are several inexpensive ways to introduce this concept. For those faculty and students who already own smart phones, assistance can be offered to download, calibrate, and interpret sound-level meter applications. Although 47% of the faculty and 35% of the students expressed an interest in this option, it is possible that interest will rise with the increase in the number of people with access to smart phones. Also, as more information is provided about the potential for risk even in classical music, there may be an increase in interest for this service.

There is another means of introducing the issue of personal sound exposure levels. About half of the respondents expressed an interest in measuring the levels coming from their iPods. This could be an entrée to increasing their curiosity about sound levels during practice, rehearsal, and performances. A clever means of providing this information is through the use of a mannequin called “Jolene” invented by Genna Martin, which houses an inexpensive sound level meter and simulates the ear transfer function when an earphone is attached to the mannequin (for more information, including how to build Jolene, see http://www.dangerousdecibels.org/education/jolene). Levey et al23 used “Jolene” to measure iPod volume outside a subway station; thus, it could easily be set up at an appropriate location in the school.

Annual hearing screening. The most enthusiastic response to a survey question from faculty and students related to the prospect of a free annual hearing screening by the college. As noted earlier, in a survey of the musicians in three Danish orchestras, Laitinen and Poulsen19 found very different percentages of frequency of hearing testing; only 35% had been tested within a 3-year period, which they compared to an earlier study where 85% of the Finnish musicians had reported being tested. This demonstrates wide variability and the potential to increase hearing testing in a musician population.

Callahan et al15 also endorsed the need for annual audiologic evaluation of music students. They found that, after their short hearing conservation program, students indicated a greater inclination to have their hearing tested. An added advantage of a hearing screening is that it can provide an opportunity to offer other services and general information on hearing conservation. It has been shown among professional musicians that those who already have hearing loss are more likely to use ear protection.19

Research needs relative to crafting a program for student musicians and faculty. Further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of different approaches to hearing conservation in a college music program. Although Callahan et al15 reported that their participants felt that a 50-minute program was sufficient, more research is needed to determine the ideal length of a program. Griest et al21 found, after implementing an elementary/middle school-based 35-minute hearing loss prevention program, that although increases in knowledge and changes in attitudes were noted, short-term effects were stronger than long-term effects. Weichbold and Zorowka24 noted increases in student knowledge during a hearing education campaign involving high school students in four 45-minute sessions (spread over 3 days); however, behavioral changes (the ultimate goal) were rarer.

Health behavior change can take time. Audiologists and hearing care educators may need to view auditory conservation efforts not as a sprint, but as a marathon. In any case, we have an important role to play, and have the potential to make a substantial contribution to the changing of health behaviors among the faculty and students in college music programs.

Conclusions

1) College music faculty, as well as students, had some knowledge regarding the potential effects of loud music on hearing and the ear, but many were not familiar with all the issues needed to make an informed decision.

2) There was a lack of systematic use of ear protection, although a smaller percentage of the faculty than students reported that they did not feel the need for it.

3) A majority of faculty, as well as students, were in favor of hearing conservation education and services within the college music program; however, they differed in preference regarding the form it should take.

4) A multipronged approach by audiologists is warranted. The program should not be perceived by faculty or students as interfering with other program requirements and should include:

- Ear protection information, which was of greatest interest among respondents;

- Information on risk of loud music to hearing, which was also of interest (and may inspire willingness to try to use ear protection); and

- Desired services such as annual hearing screenings and measures of iPod volume, which may in turn lead to interest in other services and ear protection strategies.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by Research Award 64098-00 42 from PSC-CUNY. The authors acknowledge Dr Michael Ayers, S. Benjamin Kanters, and Richard Begel for their assistance in survey development/distribution, those affiliated with the BC Conservatory of Music, and Professor Bruce MacIntyre, Chair, in particular, for their help in the data collection, as well as Dr Arlene Neuman for her comments on an earlier version of the paper.

|

|

|

| Adrienne Rubinstein, PhD, and Rochelle Cherry, EdD, are professors, and Elvera Bader, BS, is an AuD student at the Department of Speech Communication Arts and Sciences at Brooklyn College and the Doctor of Audiology program at the Graduate School of the City University of New York, New York, NY. CORRESPONDENCE can be addressed to Dr Rubinstein at: [email protected] | ||

References

1. Niskar AS, Kieszak SM, Esteban E, Rubin C, Holmes AE, Brody DJ. Estimated prevalence of noise-induced hearing threshold shifts among children 6 to 19 years of age: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994, United States. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):40. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=4767123&site=ehost-live

2. Schlauch RS, Carney E. Are false-positive rates leading to an overestimation of noise-induced hearing loss? J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54(2):679-692. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0132)

3. Shargorodsky J, Curhan SG, Curhan GC, Eavey R. Change in prevalence of hearing loss in US adolescents. JAMA. 2010;304(7):772-778. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=53054712&site=ehost-live

4. Portnuff CDF, Fligor BJ, Arehart KH. Teenage use of portable listening devices: a hazard to hearing? J Am Acad Audiol. 2011;22(10):663-677.

5. Goggin LS, Eikelboom RH, Edwards GS, Maric V, Anderson JR, Sander PB, Atlas MD. Noise levels, hearing disturbances, and use of hearing protection at entertainment venues. Aust N Z J Audiol. 2008;30(1):50-58. doi:10.1375/audi.30.1.50

6. Punch JL, Elfenbein JL, James RR. Targeting hearing health messages for users of personal listening devices. Am J Audiol. 2011;20(1):69-82. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2011/10-0039)

7. Zhao F, Manchaiah VKC, French D, Price SM. Music exposure and hearing disorders: an overview. Int J Audiol. 2010;49(1):54-64. doi:10.3109/14992020903202520

8. Chesky K. Schools of music and conservatories and hearing loss prevention. Int J Audiol. 2011;50:S32-S37. doi:10.3109/14992027.2010.540583

9. Chesky K. Hearing conservation in schools of music: the UNT model. Hearing Review. 2006;13(3):44-38. Available at: /all-news/16219-hearing-conservation-in-schools-of-music-the-unt-model

10. Barlow C. Potential hazard of hearing damage to students in undergraduate popular music courses. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 2010;25(4):75-182.

11. Miller VL, Stewart M, Lehman M. Noise exposure levels for student musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 2007;22(4):160-165.

12. Phillips SL, Mace S. Sound level measurements in music practice rooms. Music Performance Research. 2008;2:36-47.

13. Phillips SL, Henrich VC, Mace ST. Prevalence of noise-induced hearing loss in student musicians. Int J Audiol. 2010;49(4):309-316. doi:10.3109/14992020903470809

14. Chasin M. Musicians and the prevention of hearing loss. Paper presented at: the 2011 American Academy of Audiology annual convention; April 6-9; Chicago.

15. Callahan AJ, Lass NJ, Foster LB, Poe JE, Steinberg EL, Duffe KA. Collegiate musicians’ noise exposure and attitudes on hearing protection. Hearing Review. 2011;18(6):36-44.

16. NASM/PAMA. Basic Information on Hearing Health: Information and Recommendations for Administrators and Faculty in Schools of Music [2011]. Available at: http://nasm.arts-accredit.org/site/docs/PAMA-NASM_Advisories/1_NASM_PAMA- Admin_and_Faculty_2011Nov.pdf

17. Zander M, Voltmer M, Spahn C. Health promotion and prevention in higher music education: results of a longitudinal study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists. 2010;25(2):54-66.

18. Callahan A, Foster L, Poe J, Lass N. Effectiveness of a noise-induced hearing loss seminar for collegiate musicians. Hearing Review. 2012;19(8):42-50. Available at: /issues/articles/2012-08_04.asp

19. Laitinen H, Poulsen T. Questionnaire investigation of musicians’ use of hearing protectors, self reported hearing disorders, and their experience of their working environment. Int J Audiol. 2008;47(4):160-168. doi:10.1080/14992020801886770

20. Zander MF, Spahn C, Richter B. Employment and acceptance of hearing protectors in classical symphony and opera orchestras. Noise Health. 2008;10(38):14-26. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=30001541&site=ehost-live

21. Griest SE, Folmer RL, Martin WH. Effectiveness of “dangerous decibels,” a school-based hearing loss prevention program. Am J Audiol. 2007;16(2):S165-S181. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2007/021)

22. Huttunen KH, Sivonen VP, Pöykkö VT. Symphony orchestra musicians’ use of hearing protection and attenuation of custom-made hearing protectors as measured with two different real-ear attenuation at threshold methods. Noise Health. 2011;13(51):176-188. doi:10.4103/1463-1741.77210

23. Levey S, Levey T, Fligor BJ. Noise exposure estimates of urban MP3 player users. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54(1):263-277. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0283)

24. Weichbold V, Zorowka P. Can a hearing education campaign for adolescents change their music listening behavior? Int J Audiol. 2007;46(3):128-133. doi:10.1080/14992020601126849

APPENDIX

Download a PDF of the entire survey and responses, Click here.