The ear—in the anatomical sense—does not recognize the difference between classical music, rap music, or rock and roll. It does not distinguish between music or motorcycles or marching bands. If a noise is too loud, it is too loud, melodic or not.

“It’s all the same to the ear,” says Lawrence Hable of Amplifon USA, Plymouth, Minn, and secretary of the American Hearing Research Foundation (AHRF), Chicago.

Too loud—in terms of noise-induced hearing loss or NIHL—is typically defined as exposure to noise that is 85 decibels or greater for a period of 8 hours or longer. Louder noises can be tolerated for shorter periods of time. Expose the ears to loud noises for too long, and irreversible damage can be inflicted.

The progress of NIHL may vary, but hearing loss typically occurs in the higher frequencies first, sometimes mirroring symptoms experienced from presbycusis, or age-induced hearing loss. Audiometric symptoms can distinguish the two, but when experienced together, symptoms are compounded. Often, tinnitus is also diagnosed.

Treatment is typical: assistive listening devices (ALDs), hearing aids, and (if hearing loss has progressed far enough) cochlear implants. Hearing protection is equally as important, if not more so. Used properly, it can slow the progression of NIHL or can be used to prevent it.

In workplace situations such as construction sites, factory floors, and airports, regulations enforcing the wearing of hearing protection exist to protect employees. Mandated testing also ensures that no loss has occurred. At play, however, people are free to listen to volumes as loudly and as freely as they wish.

|

| Brad Witt, CCC-A |

Musicians, dance clubbers and concertgoers, hunters, motorcycle enthusiasts, and wood and metalworkers are just some of those exposing themselves to hearing damage from excessive noise that could be avoided by lowering the volume or wearing adequate hearing protection. Succeeding generations have faced unique hearing challenges: those who fought in World War II experienced damage related to gun and artillery fire; Baby Boomers attended extremely loud concerts—their generation danced next to the first “wall of sound.” Today’s generation enjoys personal portable soundtracks, delivered wherever and whenever directly to their ears.

With industry advocates supporting more research to help discover new ways to prevent and treat sound loss, studies presently under way are investigating the molecular process of hearing damage and repair, and researching whether antioxidants or drugs may have beneficial effects. In the meantime, Brad Witt, CCC-A, believes that the hearing community should focus on prevention.

An audiologist manager for Sperian Hearing Protection, Smithfield, RI, Witt says, “We often define it with a handful of Ps: NIHL is painless, permanent, and progressive, but also very preventable. We have no pill, no surgery, no therapy to repair NIHL. We simply do our best to remediate it through amplification. And so prevention through protection is the most important message we try to send in our education efforts.”

STUDYING THE GENERATION GAP

It’s uncertain how well that message is currently getting across, particularly since there is a small amount of controversy over how much damage new technological devices can be expected to create. Peter M. Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, associate professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, and director of clinical services for the Occupational and Environmental Medicine Program at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn, explains that there are no certain statistics on how many suffer from NIHL, but one estimate is 13 million.

The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, Bethesda, Md, estimates some 22 million Americans may have suffered permanent damage to their hearing as a result of excessive noise exposure, and the American Hearing Research Foundation suggests it is as many as one in 10.

A study conducted by Amanda Sue Niskar et al and published in the July 2001 issue of Pediatrics found that of US children 6 to 19 years of age, potentially 5.2 million or 12.5% had experienced noise-induced hearing threshold shifts.

“I think today’s devices are potential problems, but we haven’t completely proven it yet. Every generation has been exposed to excessive levels of noise in different ways, but whether this generation is the worst, we don’t yet know. We are watching it closely,” Rabinowitz says.

Witt concurs: “Despite the anecdotal reports in the press about the ‘iPod generation’ losing its hearing, we do not yet have many population studies confirming that massive numbers of users are suffering NIHL. But most experts agree it will just be a matter of time before those kinds of demographic data do start to show increased hearing loss.”

Sigfrid Soli, PhD, feels it’s a bit early to blame NIHL on the iPod. Soli, the head of the Department of Human Communications Sciences and Devices at the House Ear Institute (HEI) in Los Angeles, says, “iPods have been around only a few years and are not capable of causing the noise trauma necessary for hearing loss in that short time frame. The effects are slow and cumulative, and so it’s too early to have that evidence right now. But it’s not too early for parents to advise their children to lower the volume, and to follow that advice themselves.”

Soli suggests new studies will have to look specifically at the fact that today’s technology users are much younger. Another factor to be investigated is the delivery of sound directly into the ear canal. “It’s a new way to expose ourselves to sound and so wasn’t considered by those who developed noise-level standards based on occupational data,” Soli says. He notes that these models are based on adults exposed to occupational noise for 40 years, not the person who has listened to music through headphones since the age of 12.

TESTING TESTING…

In many instances, it is difficult to separate presbycusis from NIHL. Both show similar patterns of loss, starting at the higher frequencies and moving out from there. NIHL is often characterized by a noise notch in the audiogram in the frequency range of 3,000 Hz to 4,000 Hz. Soli notes that these notches are not found in presbycusis. A patient history and physical examination will round out the diagnostic process. Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) can also be used.

“Otoacoustic emissions have been used to show damage to outer hair cells, which are the first to be impacted by excessive noise. By the time a patient has developed a 40% to 50% hearing loss, those hair cells are irreparably damaged,” says Dave Fabry, PhD, a new associate professor of audiology at the Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami. Fabry was formerly vice president of professional relations and education for Phonak Inc, US, Warrenville, Ill.

The benefit of OAEs is that they provide an objective measure. “The test measures the activity of the hair cells themselves rather than testing behavior—that of pushing a button when a tone is heard,” says Rabinowitz. Whatever method is used, screening for NIHL does not differ from that required for other hearing diagnoses, though it may take place more frequently in certain industries.

People in high-noise occupations (those where employees are exposed to sound louder than 85 dB for periods of 8 hours or more) undergo regulated testing to monitor for hearing threshold shifts that indicate damage, with comparisons made to a baseline. The test also helps to determine whether the individual is using the proper protection.

Proper fit and use are key to effectiveness. Witt cites a study that found that one third of workers (out of 100 tested) achieved up to 30 dB less attenuation than the rating number because their earplugs had been inserted improperly. Therefore, checking compliance may need to be more about fit than actual use.

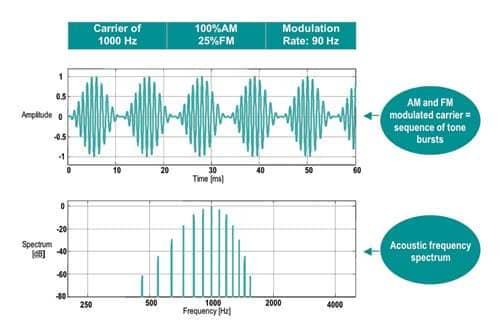

The ability to detect improper use means that fit or insertion can be corrected before damage occurs. HEI has developed a device intended to measure hearing protection effectiveness. The technology has been licensed to a manufacturer that debuted a prototype in October 2007. To complete the testing process, the individual being tested listens to sound in each ear through a pair of headphones. The loudness is modifiable in one ear only, and the user adjusts it so the volume in each ear matches. The test is then administered again with one earplug in and then the other.

“The difference tells you how much attenuation the individual is getting from the hearing protection,” says Soli. The test takes about 1 minute and is intended to provide workers with the ability to tell when they are adequately protected.

In the past, the primary emphasis in hearing protection was to block noise. “That emphasis fostered the misconception that more protection is always better. Today, we’ve gotten away from that attitude. The focus is definitely more on ‘managing the sound’—reducing the hazardous noise to a level that still allows communication and warning signal detection,” Witt says.

POUND OF CURE

Witt believes the first line of defense against excessive or hazardous noise exposure consists of engineering controls, such as enclosures, dampeners, and mufflers. Next are exposure controls. “Rotating workers more frequently out of hazardous noise areas or moving maintenance and housekeeping personnel to the second or third work shift when noise levels may be lower,” he says.

If these measures do not bring noise to safe levels, personal protective equipment, such as earplugs and earmuffs, provides the final layer. Witt judges them to be capable of protecting the vast majority of noise-exposed workers when used properly. “A well-fit foam earplug, for example, blocks about 30 dB of noise. That translates into a 1,000 times reduction in the sound energy,” says Witt.

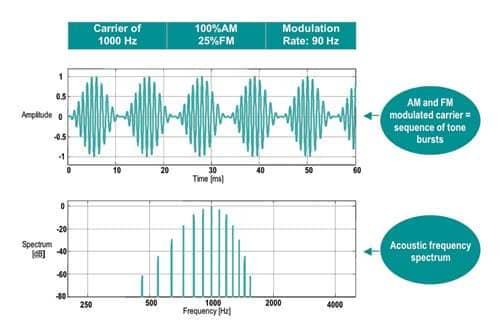

Newer technologies are able to dampen loudness without impacting tone. One method, according to Witt, is protectors with “flatter” attenuation characteristics. “This flatter response creates a sound under the protector that is more natural. It still blocks the noise, but with less distortion for speech and warning signals. We turn down the ‘volume’ of the incoming sound without turning down the ‘tone’ control,” Witt says.

An example would be earplugs designed for musicians that attenuate the sound equally across all frequencies while avoiding the effects of occlusion. “Musicians have balked at hearing protection in the past because earplugs upset the balance of sound. Newer models turn everything down a little without changing the frequencies,” says Fabry.

Sound amplification earmuffs permit workers to better hear what they need to hear while reducing excessive noise. “Sound amplification earmuffs have microphones placed directionally on the ear cups and amplify normal sounds to a safe level, while still [protecting users] from the hazardous workplace noise,” Witt says.

Fit is extremely important. An improper fit can mean zero protection. “Studies have shown that one half of the workers wearing hearing protectors receive one half or less of the noise reduction potential of their protectors because these devices are not worn continuously while in noise or because they do not fit properly,” says Witt. For this reason, devices, like that developed by HEI, can help to improve preventive measures, particularly in the workplace where they are more likely to be used.

Once hearing is impacted, treatment is limited to the devices available for all other types of hearing loss.

“Currently, treatment of NIHL is limited to hearing amplification and counseling, but hearing aids are not perfect,” Rabinowitz says.

They are better than they were in the past. Micro BTE devices in particular seem well suited to this group: they amplify high-frequency sounds, they avoid occlusion, and they tend to be very unnoticeable. But Rabinowitz doesn’t feel they fully correct problems with speech discrimination.

Hearing aids can also help to mask the sounds of tinnitus, which sufferers may find difficult to ignore. Retraining therapy may also be helpful. But the best method is prevention. “I think one of the things we as professionals always need to do is to make the public aware of noise in everyday surroundings and help educate them about prevention, rather than trying to fix them after the damage is done,” says Fabry. So, turn it to the left.

POINTERS FOR PERSONALIZING PROTECTION

“If you have 30 people in the room, there could easily be 30 different choices of the best hearing protector,” says Brad Witt, CCC-A, audiologist manager for Sperian Hearing Protection, Smithfield, RI. Factors impacting the selection of hearing protection include:

- Comfort: “An uncomfortable earplug spends more time in the pocket than in the ear,” says Witt.

- Noise reduction and communication needs: “How much protection does someone need in a particular environment? Too much and it’s too difficult to communicate, too little and hearing can be damaged,” says Peter M. Rabinowitz, MD, MPH, associate professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, and director of clinical services for the Occupational and Environmental Medicine Program at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn. Users of hearing protection want to protect their ears but still be able to hear coworkers, alarms, and other necessary sounds.

- Size: Size matters.

- Special needs: These match the occupational specialty. Examples provided by Witt include facilities, such as food processing or aerospace manufacturers, that may require corded earplugs to avoid contamination of the product or workers at railyards and airports who often wear high-visibility earmuffs for accident prevention.

- Cleanliness: Earplug designs for industries where sanitation is a particular concern eliminate the need to hold parts that go into the ear canal, notes Witt.

- Compatibility: What other safety gear must be worn? Cap-mounted and behind-the-neck earmuffs can be worn with hard hats or safety visors.

Renee DiIulio is a contributing writer for Hearing Products Report. For more information, contact [email protected].