How dispensing audiologists can develop an organic communication strategy aimed at decreasing the negative emotions that accompany hearing loss.

By John Greer Clark, PhD

When something occurs organically it happens or develops naturally, without pre-planning or a sense of being forced upon the situation. Often the communication guidance we provide is most readily accepted when it evolves the clinical exchanges we have daily our patients. But while a communication management suggestion may come up “organically,” it will be most readily embraced when accompanied by reflection on the comfort a patient may have in its real world use.

This article looks an organic discussion focused on one of the most beneficial augmentative suggestions we can provide to patients—instruction on the patient’s introduction of clear speech to a communication partner. Such discussions need not take long, but they often present the most valuable intervention an audiologist provides in an appointment.

The benefits of clear speech

One would think that talking more slowly with a conscious effort to enunciate would become a natural speaking style for those living with someone who has hearing loss. Unfortunately, adopting a clear speaking style is not automatic. A clear speaking style takes a conscious effort to develop even for those who regularly speak with a person who would benefit from it. But it can be done.

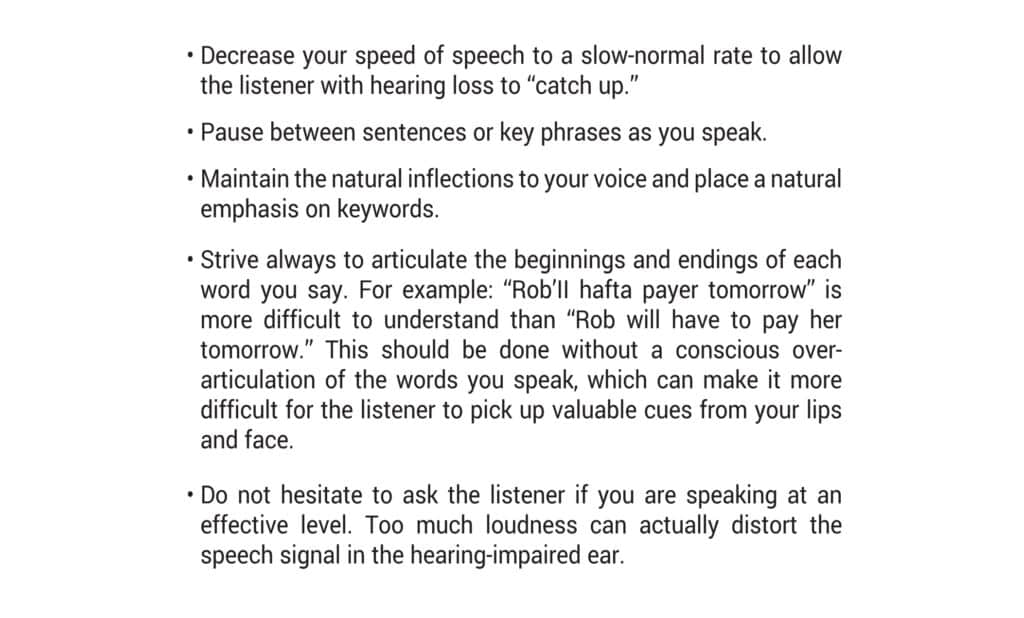

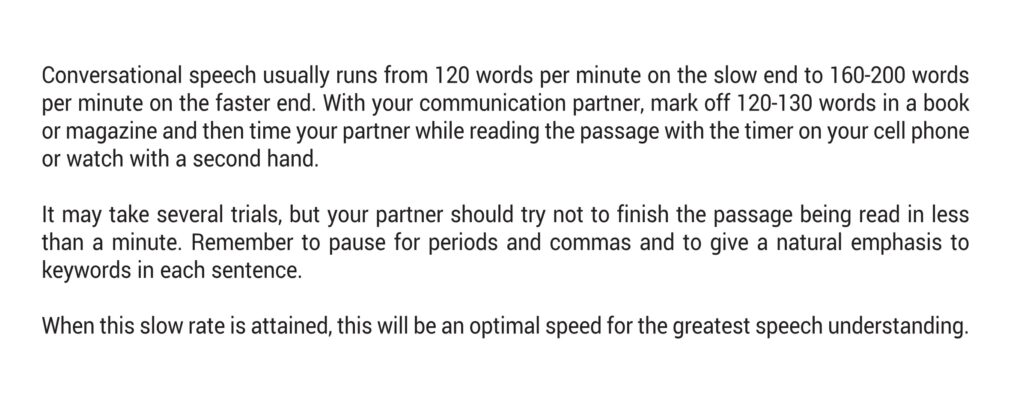

Research has consistently shown that a clear speaking style can increase understanding by those with hearing loss regardless of age and whether the speaker’s face is visible, and that the added speech intelligibility advantage increases as the listening environment becomes less favorable, such as in noisy restaurants or at parties.1 As reported by, Caissie and Tranquilla even minimal instruction in clear speech (Figure 1) can improve speech understanding by as much as 11-34% and that more specific training in this area (Figure 2) may increase comprehension by as much as 42%. Minimal instruction often includes telling someone that comprehension is significantly enhanced when the speaker talks at a slow-normal rate, strives to enunciate the endings of words without over-articulating, and pauses as they talk where commas or periods would be if what they were saying were written out.

The dilemma

Dating back to early hearing aid research,2 we know that hearing aids, the cornerstone of hearing loss management, are only capable of restoring about 50% of a person’s lost hearing. This, of course, is not due to limitations of these amplification devices but rather due to how much amplified sound the impaired human ear can comfortably tolerate. A person with a 60 decibel hearing loss whose hearing is improved to approximately 30 dB HL will clearly be functioning better. But as most with a hearing loss of 30 dB HL will tell us, this is not normal hearing and it can frequently leave a person frustrated and exhausted.

As an augmentative to the inherent limitations of hearing aids, some hearing care professionals provide new hearing aid users with a list of communication enhancement suggestions such as to ask others to speak more slowly, to converse in the same room they are in, to move away from the source of interfering noises, and so on. But as advantageous as these suggestions can be, a survey of clinical practices found that only 19% of responding audiologists provide this information to their patients on a routine basis.3 Clearly we can do better to provide this information. We also need to do more to promote its active use.

The dilemma arises when we make the assumption that providing communication suggestions to patients will result in their use. When provided, these suggestions are given with the best of intentions and with a clear nod to the recognition that more is needed than amplification in many situations. But without discussing the patient’s perceived comfort in using communication strategies, they frequently are not used.

Why might this be true? Dr. Brené Brown, the renowned vulnerability researcher, sheds light on the reason when she writes that “Fitting in is the greatest barrier to belonging.” 4 When patients make an effort to use communication suggestions to improve hearing beyond the limitations of what technology (e.g. hearing aids) can provide, they quickly find they need to set themselves apart from others. They need to draw attention to their difference. They need to discuss their hearing loss. They need to tell others what others need to do for them. They need to step outside of the comfort of conformity; and by one’s very nature, patients often find this difficult.

Despite the fact that western culture values individuality, research has demonstrated that humans adjust their actions to be more aligned with that of their peers in an ongoing effort to not stand out from the group, to not be perceived as different. Yet, when patients succumb to this strong desire to fit in, their need to express what might aid better communication is stymied.

Because of the ingrained desire to fit in and not draw attention to our differences, it becomes imperative that the introduction of any communication enhancement strategy be accompanied with some discussion of the patient’s perceived comfort with its use and the validity of anticipated responses to reasonable requests to aid comprehension. The following example dialogue demonstrates how this may be done within a routine clinical visit with recognition of the many time constraints that audiologists work within. The discussion, along with the provision of an accompanying handout, can be as brief as five minutes while providing invaluable assistance to the recipient.

An organic discussion of clear speech

In this example of organic communication management, we might envision an audiologist finishing a routine maintenance check with a patient we will call Sylvia. Sylvia suddenly looks at the audiologist and says, “I think my son-in-law hates me.”

The audiologist looks back at her, holding a silence to see if she might elucidate. Then, after a few moments in silence, and reflecting on the fact that the topic sounds outside of his scope of practice, he replies, “Sylvia, what makes you think he hates you?”

“Oh. I don’t know,” she responds, followed by, “He just doesn’t seem to care if I understand what he says to me. It makes me feel so excluded sometimes. Or stupid. He talks so fast—all the time. I’ve asked him to slow down, and he will for a sentence or two. But then he goes right back to it. He doesn’t care.”

Again, the audiologist pauses for a moment to let her words sink in, for him and for her. “Can I offer a different perspective?” he says. “Something you might want to consider before assuming he hates you.”

“You mean something other than he doesn’t want to be bothered to speak slower for me?”

“Yes,” the audiologist replies. “Maybe you need to cut him a bit of slack. He’s probably spoken very rapidly his entire life. And it works for him. Always has. And now this new person in his life—you—has difficulty hearing him when he talks fast. And you’re the only one. And he has to remember to change a lifetime habit of fast speech for just you on his occasional visits. I’d say it’s a big ask. I’m not saying you shouldn’t ask him to speak more slowly. I’m just saying you should expect that he’s going to forget and slip back into his usual way of talking.”

“Well, I can’t keep asking. I’ve told him to slow down so many times he’s probably nearly as annoyed with me as I am with him.”

“You’re right, people can find it annoying if you keep interrupting what they’re saying. But there is another solution.”

And then the audiologist describes Clear Speech to Sylvia (Figure 1). Following the explanation of clear speech, Sylvia responds, “He’ll never remember to do that. And I’m sure he wouldn’t appreciate me reminding him all the time.”

“Well, you’re right about that. But there is a subtle way to give a reminder without interrupting your son-in-law. After you tell him that you really wish you could understand him better, and what clear speech is and how it will help you, tell him that you know it’s easy to forget to speak slower and that if he sees you put your index finger to your chin it’s just a gentle reminder that you aren’t getting it.”

The audiologist pauses and looks at her furrowed brow. “I know it’s important to you to understand as much as you can,” he says. “But, let me ask you, on a scale of 1 to 10, how comfortable are you with the thought of presenting all of this to your son-in-law?”

It is not surprising to the audiologist when Sylvia gives a low comfort ranking to the clear speech suggestions. As discussed earlier, it is not always easy to openly identify our needs when by necessity it involves discussing how we are different, or when we have untested fears of how another might react to our requests. Sylvia’s fears lessen somewhat and her ranking rises a bit when they discuss together the true likelihood of her son-in-law rolling his eyes and walking off after hearing about clear speech.

The audiologist ends their discussion with encouragement for Sylvia to practice her introduction of clear speech with someone she might be more comfortable with, a long-time friend perhaps—regardless if she needs that friend to use clear speech or not—just to see what the reaction would be and what that person thinks of the idea.

With the brief guided introspection the audiologist provided, and a “practice” introduction of the topic with a friend, Sylvia later reports that she finally broached the topic with her son-in-law. As the audiologist expected, it was better received than Sylvia had thought it would be.

Our challenge

In contrast to audiologic services provided by practitioners in the formative years of our profession, in today’s practice of audiology the fitting of hearing aids and subsequent hearing aid management is unfortunately often considered the totality of the audiologist’s rehabilitative services. We need to remember as the implicit reason that patients seek audiologic services is not for hearing aids per se, but because they are seeking ways to minimize the many hearing-related problems they encounter on a daily basis.5 Given that hearing aids can only restore half of the degree of lost hearing, we can expect that these hearing-related problems will, to some degree, continue after the hearing aid fitting. This is exactly what Kochkin and Rogin reported over 20 years ago—what we already knew, that untreated hearing loss increases levels of depression, anxiety, anger, and frustration. What they further reported was that these same emotions were present with hearing aid users—just to a quantifiably lessor extent.

When we are with patients we need to remain vigilant for patient comments that speak to residual hearing difficulties that are inevitably present even with the best fit, most advanced technologies. Then we need to be prepared to provide appropriate suggestions and to explore with patients the perceived comfort they may feel in using suggestions and the impediments patients may foresee in their use.

These discussions do not have to take long and do not derail the intended purpose of the appointment. Looking back at the clear speech example with Sylvia we see the dialogue lasted less than 5 minutes. But it likely was the most valuable intervention the audiologist provided in that appointment. With similar discussions toward organic communication management, audiologists can provide an invaluable service aimed at further decreasing the negative emotions that accompany hearing loss. HR

Author Bio

John Greer Clark, PhD, is a professor emeritus at the University of Cincinnati, a past president of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology and a past chair of the American Board of Audiology.

References

- Uchanski R.M. Clear speech. In D.B. Pisoni & R.E. Remez (eds.), The Handbook of Speech Perception. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 2005;(207-235).

- Lybarger S. Method of fitting hearing aids. U.S. Patent Applications S.N. 543,278. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. July 3, 1944.

- Brown B. Atlas of the Heart. New York: Random House. 2021

- Clark JG, Huff C, Earl BR. Clinical practice report card: Are we meeting best practice standards for adult hearing rehabilitation. Audiology Today. 2017;17:14-25.

- Ross M. Aural rehabilitation: Some personal and professional reflections. The Hearing Review 2001. Accessed February 20, 2023. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/hearing-loss/patient-care/aural-rehabilitation-some-personal-amp-professional-reflections