Viewpoint | February 2021 Hearing Review

By Emilie K. Clark, LMSW; Ashley L. Koenig, MA, and John Greer Clark, PhD

Surveys suggest that 4.5% of American adults, and an even greater percentage of American youth, openly identify as LGBTQ. About one-sixth of LGBTQ adults say they have experienced healthcare discrimination. Unacknowledged implicit bias has detrimental impacts in our interactions in the clinic and the larger venues of our lives, even when we believe ourselves to be nondiscriminatory. Here are some ideas and guidelines for making your practice more welcoming and comfortable for everyone.

Nearly one-sixth of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) adults have experienced healthcare discrimination with nearly that many avoiding care for fear of discrimination.1 While the issue of affirmative practice with members of the LGBTQ community has been addressed in medical literature before, practitioners are often uncertain how to modify their clinical interactions and administrative practices to facilitate greater access and comfort for LGBTQ patients.

Patients who seek hearing care services come from varying backgrounds with unique life experiences. How patients view us as practitioners begins with their initial contact with our office staff who serve as the “ambassadors of first impressions.” The tone of voice conveyed by the staff member who answers the first phone call, the language of our intake paperwork, even our own greeting when we meet the patient in the examination room, are pivotal to subsequent successful interactions.

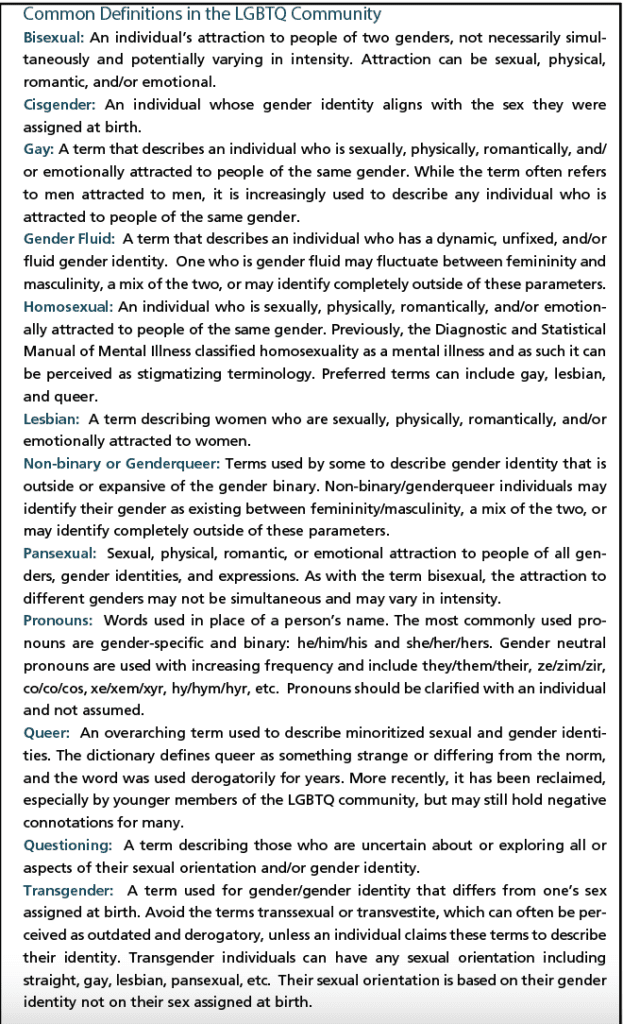

While most practitioners have a growing awareness of how they may interact with patients whose ethnicities and cultural backgrounds differ from their own, we frequently fail to recognize biases that interfere with the successful interactions we seek with patients from LGBTQ communities (see “Definitions”5 in online version of article). We all hold varying degrees of unconscious preconceptions (ie, implicit bias) toward those perceived as different, whether based on race or other aspects of physical appearance, ability, socio-economic status, gender, sexual orientation, and the countless factors that encompass identity.

Unacknowledged, implicit bias has detrimental impacts in our interactions in the clinic and the larger venues of our lives, even when we believe ourselves to be nondiscriminatory. One way to combat the negative impact of implicit biases is to acknowledge our internalization of societal stereotypes and work to counter the preconscious notions we hold toward others. A useful tool for beginning such critical introspection is the Harvard Implicit Association Test (http://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/india/takeatest/html).

This article explores assumptions about sexual orientation and gender identity often made in clinical settings and offers suggestions to facilitate affirming and inclusive clinical environments.

Inaccurate Assumptions of Patient Demographics

Surveys suggest that 4.5% of American adults, and an even greater percentage of American youth, openly identify as LGBTQ.2,3,4 Numbers seem to peak with the youngest cohort in a given era. The Trevor Project2 estimates that upwards of 10% of those born between 1999 and 2004 identify as LGBTQ. Among the Millennial population cohort (those born between 1980 and 1999), 8.2% identify as LGBTQ with progressively fewer self-identifications for Generation X (3.5% for those born between 1965 and 1979), Baby boomers (1946-1964 at 2.4%), and Traditionalists (1913-1945 at 1.4%).3

These numbers tell an important story of decreasing stigma against the LGBTQ community, with younger cohorts having grown up during a cultural time in which the nuances of sexuality and gender are increasingly accepted.4 Still, it is important to note that stigma persists, especially outside of major metropolises. Furthermore, noted prevalence statistics do not capture countless individuals who are unwelcome or unsafe to openly claim their identities. Despite the prevalence of LGBTQ identity, many clinics and practitioners operate under the assumption that their patients exclusively identify as straight and cisgender.

Maintaining an Open and Nonjudgmental Space

Paramount to a welcoming and comfortable experience for any patient is the sense of emotional security provided by a practitioner’s unconditional positive regard for those served. Professional codes of ethics dictate that patients be treated in accordance to the rights, dignities, and privileges afforded to all people regardless of race, ethnicity, national origin, culture, religion, sex, gender identity/gender expression, or sexual orientation. Beyond what is stated within professional ethics documents, practitioner “unconditional positive regard” (ie, the provider accepting and caring for the whole person without judgment) requires that we accept and embrace each of our patients’ identities. Just as we work to leave our personal lives at the door and give our full commitment to our patients’ communication needs, so too must we divorce our opinions and personal beliefs from the respect we impart to our patients. Respect requires that we hold space for our patients’ identities and forms of expression to create an experience that is welcoming, safe, and compliant with our ethical mandate.

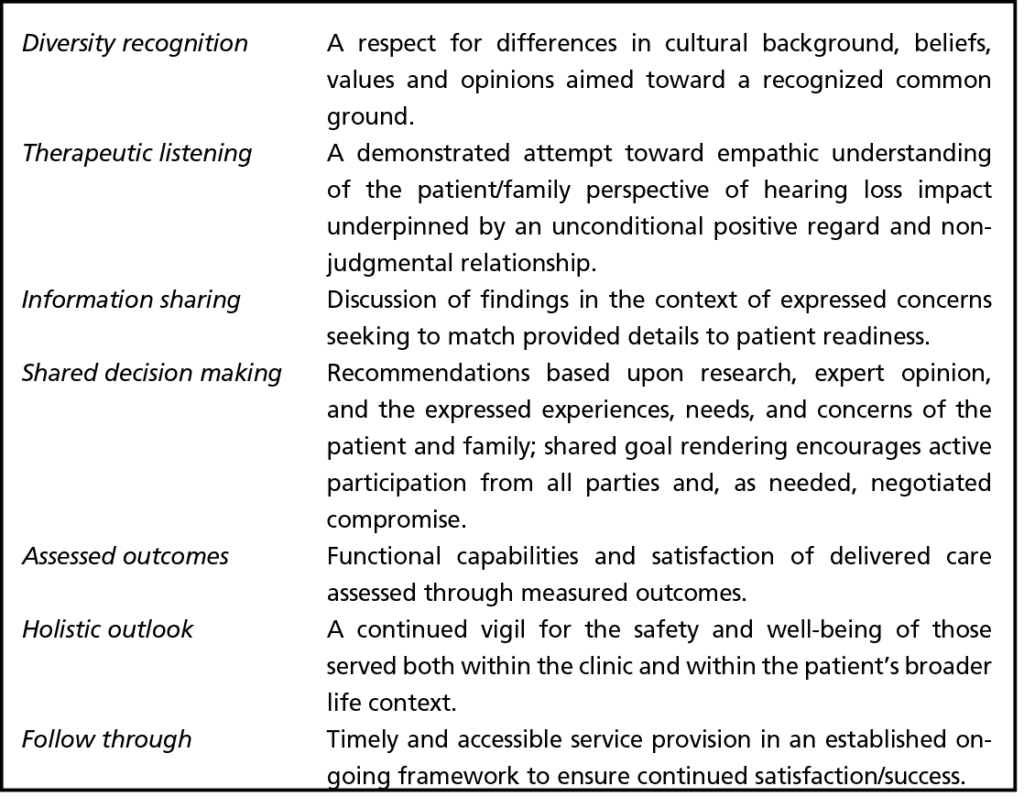

Effective healthcare services, including hearing loss management, is predicated upon the successful development and maintenance of a positive and interactive relationship between patient and provider. The first two components of person-centered care—diversity recognition and therapeutic listening—are foundational to this desired relationship (Table 1).

While discrimination in healthcare environments may be rooted in an individual provider’s personal homophobia or transphobia, discrimination is complex and multi-leveled— and most often unconscious and unintended. On the micro level we find discriminatory and unwelcoming environments created through unintended slights, misstatements, or actions on the part of a healthcare provider and staff members. On a more macro/systemic level, discrimination looks like binary assumptions on insurance-compliant paperwork, restricted lists of domestic relationships, etc. To aid in clinician interactions with LGBTQ patients, the following may be useful.

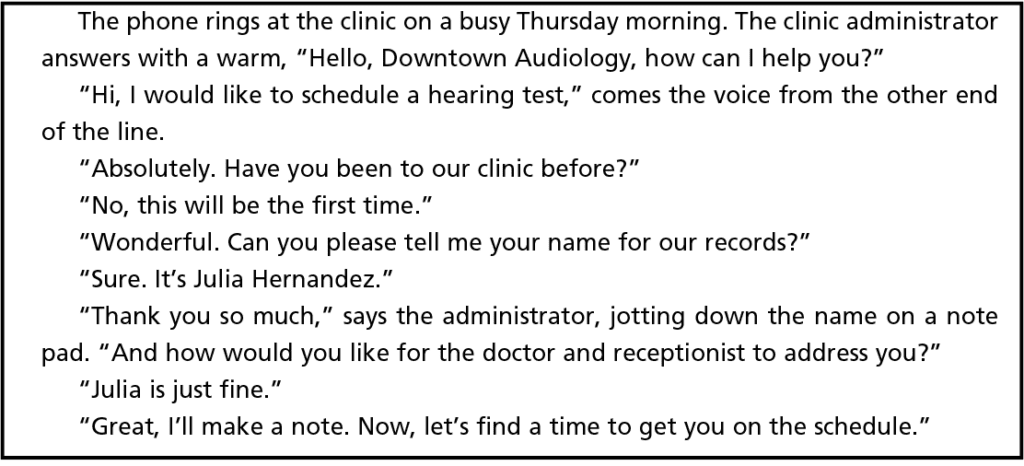

Greeting patients on the phone, at reception, or in the examination room. We should not assume how a patient would like to be addressed and therefore should avoid greeting patients on the phone or in person with “sir” and “ma’am.”Using suffixes like Ms, Mr, and Mrs in first encounters pose a similar problem. Instead, start with a simple “Good morning/afternoon, what brings you in today?” As soon as appropriate in the conversation, it is helpful to ask patients how they would like to be addressed (see the sample dialogue farther down on the page). Consider having a system for recording patients’ responses (see below) so that patients do not have to answer the same question numerous times and are addressed correctly by all office staff.

Mismatched records. There are significant logistical and often financial hurdles to obtaining name and gender changes on legal identification documents, and many people may use a name different from their legally recognized name without a desire to change their documentation. Additionally, changing one’s gender on legal documents and insurance records can affect treatment options in some cases.6 For example, someone who makes a legal change to the gender listed on state-issued documents may have trouble receiving reimbursement for treatments that are thought to be correlated to one specific gender. Due to these factors, paperwork pertaining to some patients, specifically transgender and non-binary patients, may not always be consistent. Patients must complete insurance forms with the name and gender listed on their state-issued documents (ie, male or female) whereas they may list a different name or gender on case-history or intake forms. If encountering discrepancy in responses on paperwork, be sure to use the name and gender marked on patient history forms, not insurance forms, both when addressing the patient directly and when discussing the patient with colleagues.

Paperwork suggestions. When possible, include the following in demographic questions on paperwork:

- Name: Provide a brief addition such as “How should we refer to you in the office?” This is good practice both for those who do not use their legal name, as well as for those who prefer a more formal “Mrs Jones.”

- Prefix: Expand options beyond Mr, Ms, Mrs, and Dr to include gender neutral Mx, none of the above, and fill-in-the-blank options.

- Pronouns: Similarly, given the fact that language is constantly evolving, a multiple-choice format for this question may include the following options: she/her/hers, he/him/his, they/them/theirs, ze/zir/zirs, followed by a fill-in-the-blank option.

- Gender: While gathering gender-related information may be useful for clinical and marketing purposes, asking an individual to disclose private information about their identity makes the inclusion of a fill-in-the-blank option appropriate.7,8

- Partnership. Most demographic forms use a very limiting set of options to understand a person’s state of partnership: “married,” “single,” “divorced,” or “widowed.” If you deem this question necessary for your paperwork, add options such as “domestic partnership,” “long-term relationship,” and “multiply partnered.” Note that this question should not be used to determine the composition of the patient’s household, which can instead be obtained with a more direct question.

- Consent for recording information. Add a question following demographic information for patients to confirm or deny consent for their personal identification information to be recorded in their electronic health record.

Create a system for sharing pertinent information. To ensure that patients are addressed correctly and not unnecessarily re-questioned, clinics should develop a protocol for internally sharing pertinent patient information. This may include a note on a patient’s electronic health record or physical documents.

Special considerations when working with minors. If caregivers fill out demographic forms, providers can confirm name and pronouns privately with younger patients, if possible, with a simple “What would you like me to call you?” and “What pronouns do you use?” Be mindful not to single out patients with these questions, but instead incorporate this as a part of your introductory procedure with all patients.

Young patients may disclose identity information including pronouns, gender identity, sexual orientation, and chosen name to their healthcare providers but may not have shared that information with their caregivers or other members of their household. Providers should be mindful to ask young patients who this information is shared with and not disclose identify information without the patient’s consent. This may require some code-switching, for example the pronouns you use privately with a patient may differ from the pronouns that they request you use with their caregiver. The ability to make these shifts is critical to the safety and rights to self-determination of patients, specifically those who are dependent minors.

Only ask the pertinent. When interacting with others in a clinical capacity, human curiosity can lead one to ask questions of another when differences are encountered. Clinicians must always ask themselves if their questions are pertinent to the care being provided.

Honest apologies. A lot of information has been shared in this article, and we have recommended many changes to common clinical practice. We recognize that implementing these suggestions may take time and coordination and that we are all prone to human error. Increasing consciousness of our words and interactions within clinical practice is critical. That said, everyone makes mistakes and we all may encounter moments where we have inadvertently acted insensitively.

In interactions with a patient (see dialog box above), dwelling on an insensitivity is often unhelpful and could even be harmful to the patient. Instead, it is critical to accept feedback openly when someone points out a way in which you have erred, to make a genuine apology, and to make changes wherever possible. When making an apology, try starting with “I’m sorry” followed by a “Thank you for correcting me” so as not to place the burden of reassurance on the person who has been faulted.

Conclusion

As a decrease in social stigma facilitates an increase in open proclamation of LGBTQ identity, clinicians across disciplines should be prepared to challenge assumptions and make adjustments to clinical practice to create affirming and safe environments for all patients. Modifications in clinician interactional style and clinic systems are critical to treatment success.9

Examining bias and leaning into practice adjustments can present both unique challenges as well as professional and personal growth opportunities that often are not fully addressed within our academic preparation, and therefore require actively staying abreast of changing tides of best-practice recommendations in regards to patient identity. Furthermore, making these changes can mean the difference in patients’ willingness to seek our care. It is when we make the most of these challenges and opportunities that we find we can offer a welcoming and comfortable experience for all.

Citation for this article: Clark EK, Koenig AL, Clark JG. Affirmative clinical practice with LGBTQ patients: Creating a welcoming and comfortable experience for all. Hearing Review. 2021;28(2):12-15.

Correspondence can be addressed to Dr Clark at: [email protected].

References

- Powell A. The problems with LGBTQ health care. The Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2018/03/health-care-providers-need-better-understanding-of-lgbtq-patients-harvard-forum-says. Published March 23, 2018.

- Green AE, Price-Feeney M, Dorison SH. National estimate of LGBTQ youth seriously considering suicide. The Trevor Project. Published June 27, 2019.

- Newport F. In US, estimation of LGBT population rises to 4.5%. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises.aspx. Published May 22, 2018.

- Trotta D. Some 4.5 percent of US adults identify as LGBTQ: Study. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-lgbt/some-4-5-percent-of-u-s-adults-identify-as-lgbt-study-idUSKCN1QM2L6. Published March 5, 2019.

- Koenig AL. Glossary of terms. In: MacWilliam B, Harris BT, Trottier DG, Long K, eds. Creative arts therapies and the LGBTQ community: Theory and practice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers;2019:255-268.

- Clark JG, English KM, eds. Counseling-infused audiologic care. 3rd ed. Inkus Press;2018.

- Movement Advancement Project (MAP) website. Identity document laws and policies. https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/identity_document_laws. Published February 11, 2021.

- Transgender Law Center website. ID Please CA: Full guide to changing California and federal identity document. https://transgenderlawcenter.org/resources/id/id-please. Published January 2019.

- National LGBT Health Education Center. Providing inclusive services and care for LGBT people: A guide for health care staff. https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/Providing-Inclusive-Services-and-Care-for-LGBT-People.pdf. Published February 17, 2016.