Marketing | June 2018 Hearing Review

Part 1: Consolidation and events leading up to our present market environment

To formulate any reasonable strategy for thriving in today’s hearing healthcare market, it is useful to understand where we are today, how we got here, and what might come in the future. Part 1 of this 2-part article offers a perspective about how industry consolidation has changed the hearing healthcare market and the current major trends that could influence the future strategies of an independent practice owner.

Fueled by the economic promise of an enormous Baby Boomer generation, competition has doubled and even tripled in many markets in the past few years. While some of this new competition is from independent audiologists setting up new clinics, the larger portion represents the expansion of big-box stores, franchise hearing aid sales, and manufacturer-owned hearing aid sales operations. Since branding has traditionally not been a major factor in consumer purchases,1 all of these venues are considered the same or similar by consumers, and an intense rivalry continues to evolve between independent audiology practitioners and these hearing aid sales operations.

Generally, the challenges to success and the hurdles that must be cleared by a new audiology practice in this new competitive marketplace have been discussed mostly negatively. Building an independent audiology practice is deeply personal and time-consuming, as well as financially risky. The very thought of someone else playing in your sandbox elicits feelings of rivalry, anxiety, and defensiveness.

Figure 1. US birth rates per 1,000 people as reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Baby Boomer generation (1946-1964) is highlighted in orange, representing some 76 million people. With the average first-time purchaser of hearing aids being age 63 (according to MT9), it is clear that the hearing healthcare market has a much larger sandbox in which to play. By 2029—when the last Baby Boomers turn 65—Baby Boomers will make up more than 20% of the total US population, according to the US Census Bureau.

The naysayers forget that we now have a substantially larger sandbox in which we can all play (Figure 1). Our challenge, however, is not to leave the sandbox but to find the correct place in the sandbox to build our castles. To fully understand competition, we need to appreciate that industries, such as audiology and hearing aid dispensing, naturally evolve and are constantly changing according to technology, knowledge, and economics. The process of adjusting business operations to meet these new competitive challenges requires an understanding of:

- Why does this happen?

- When and how did this happen?

- What is the result of the process?

Industry Consolidation: Why Does This Happen?

Myers2 indicates that natural industrial evolution is almost inevitable and begins by consolidation or integration of product manufacturers. Bofah3 describes industry consolidation or integration as a process that begins with product manufacturers purchasing or obtaining a controlling interest in other companies within the same industry, resulting in the reduction of competitors within that industry. The main goal of corporate consolidation is to grab market share, cut costs, boost productivity, gain patents and technology, as well as improve investment returns through economies of scale. Industry consolidation is usually characterized by one of these three categories:

- Horizontal integration combines similar companies and products within an industry and, as a result of binding the companies together, the purchasing company becomes larger and often realizes greater market share.

- Vertical integration consolidates companies so that each member of the supply chain produces a different product or service that works together to satisfy the common needs of the corporation.

- Forward integration is a vertical business strategy whereby business activities are expanded to include control of the direct distribution of a company’s products to the consumer. A good example of forward integration is the sale of hearing aids directly to the consumer by manufacturers, bypassing audiologists, other dispensers, and other outlets. Forward integration is a deliberate operational strategy implemented by a company that intends to increase control over its distribution channels, so it can increase its power over the market. For a forward integration strategy to be successful, a company needs to gain ownership over businesses (or practices) that were once customers, such as the purchase of independent audiology clinics and hearing aid dispensing practices.

In the author’s recent book4 with Robert Glaser, we suggest that an excellent historical example of natural industrial consolidation is the auto industry. Consider that, in the early part of the 20th century, there were literally hundreds of small automobile companies in the United States. For a few years, they all flourished as companies struggled to manufacture enough cars to meet consumer demand. Initially, the need for vehicles was so great that consumers did not care too much about brand—only that automobiles were available, affordable, and offered reliable transportation.

After a few years, the large demand for vehicles diminished and, by the mid-1920s, these small automobile companies struggled against each other, as well as the larger more- efficient competitors, for essential manufacturing materials and market share. Many of the smaller, less-efficient companies eventually went out of business or were purchased by the larger, better-managed automobile companies.

To compete with these larger companies, the surviving smaller manufacturers banded together into buying groups to purchase their building materials in bulk and, in return, they were given more favorable prices. Although those that banded together had to deal with buying group politics and other issues, the non-buying group participants paid a higher price for component parts, metals, and rubber, as well as other essential materials. This resulted in these companies having less funds for marketing and other operating expenses.

In the auto industry, a shining example of consolidation was General Motors under the leadership of Alfred P. Sloan, Jr (Figure 2). In the 1920s and 1930s, Sloan and his staff invented the concept of planned obsolescence by putting a new emphasis on largely cosmetic annual model changes and a planned 3-year major restyling that coincided with the service life of the factories’ production tools. The goal was to make consumers want to “bring in and trade up” to a new and more expensive model long before the useful life of their present cars had ended. Sloan’s philosophy was “the primary object of the corporation…was to make money, not just to make motorcars.”5

Figure 2. Alfred P. Sloan, Jr, the key competitor of Henry Ford, headed General Motors for decades, transforming it into the largest corporation in the world during his tenure.

By the 1950s, industrial consolidation and other innovative corporate philosophies had dwindled the major competition down to the “Big 3” automakers: General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. Later, having horizontally consolidated as much as possible, vertical consolidation began and flourished as the automobile manufacturers began their purchase of companies that used to make the engines and other vehicle components.

Forward integration also began by purchasing dealerships to offer their products directly to consumers. Although they purchased dealerships outright, they also offered loans and other incentives to the dealers that, over time, were difficult to pay back and eventually the manufacturers took over the dealerships. This acquisition process was so successful that the manufacturers eventually owned a significant number of distribution points, where they could manufacture the products with components from companies they owned, and could sell the finished vehicles directly to the consumer without the “middleman” taking a share of the profits. This put the “Big 3” auto manufacturers in full control of both the manufacturing and distribution of their products, greatly increasing profits.

This story might sound familiar to those in the hearing industry, particularly for independent practitioners who are currently dealing with intense competition. This natural industrial consolidation, both horizontal and vertical, has been going on for quite some time in hearing healthcare. In fact, the process is considered normal for any maturing industry, and the transformation of hearing healthcare has obvious similarities to the 20th century’s automobile industry consolidation. The goal of industry consolidation, to restyle Alfred Sloan’s quote, is “to make money…not just hearing aids.”

Figure 3. Industry consolidation and the “Law of the Fishes”: The big ones eat the little ones, so the little ones must be fast and numerous. Image: ©Vertes Edmond Mihai | Dreamstime.com

Industry Consolidation: How and When Did This Happen?

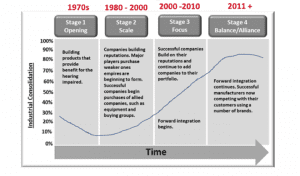

Deans et al6 report that, once the industrial consolidation process begins, there are four stages of progression:

- Stage 1: Opening. Building products that do a good job for the end user.

- Stage 2: Scale. Companies building reputations. Major players purchase weaker ones and empires begin to form (horizontal integration).

- Stage 3: Focus. Successful companies begin purchases of allied companies (horizontal integration). Vertical and forward integration begins.

- Stage 4: Balance and Alliance. Forward integration continues aggressively. Successful manufacturers are now competing with their customers—hopefully, but not necessarily, in a smart and mutually profitable manner.

Figure 4 illustrates an adaptation of the Deans et al6 model to several decades of evolution within the hearing industry. Stage 1 or the Opening stage of the consolidation process began while still working with conventional analog circuitry in the 1970s. While manufacturers were formidable competitors in the marketplace, their altruistic motives were paramount in their attempt to provide the most technological, reliable, and beneficial products for the hearing impaired.

Figure 4. The four stages of industrial consolidation, according to Dean et al.6 Graphic from Strategic Practice Managment: Business Considerations for Audiologists and Other Healthcare Professionals, 3rd Edition (p 60), by Robert G. Glaser and Robert M. Traynor, Copyright © 2018 Plural Publishing Inc. All rights reserved.

The Stage 2 or Scale period began as the digitally controlled, analog circuits were available to the marketplace in the late 1980s. Some hearing aid manufacturers were building reputations for better products over others and, due to competitive issues, horizontal consolidation began as more efficient companies purchased technologically outdated competitors. During this period, consolidations were primarily conducted to obtain patent rights, as well as for hardware, software, and programming innovations. Further, it was also to acquire valuable brand names that had not kept up with the sales and marketing of their products or that were financially troubled.

Figure 5. A list of acquisitions that took place in only the 2-year period from December 2000-December 2001 (from Strom, 20028).

The Stage 3, or Focus phase, began somewhere around the year 2000. At this point, hearing care corporate executives adopted the “Alfred Sloan philosophy” that, “the primary object of the corporation…was to make money, not just to make hearing aids.” This was summarized by Kirkwood7 who noted, “As in virtually every industry, hearing care has seen a trend of bigger companies buying up smaller companies.” Kirkwood7 and Strom8 (Figure 5) noted an especially hectic period of consolidation from 1999 to 2001 highlighted by:

- Beltone purchasing the hearing aid division of Philips Electronics.

- Starkey Laboratories purchasing Micro-Tech.

- Siemens acquiring Electone.

- GN Store Nord A/S purchasing ReSound and Beltone.

- Unitron Industries acquiring Argosy and Lori Medical Labs.

- Phonak AG (now Sonova Holding) purchasing the Argosy/Lori/Unitron group.

This flurry of acquisitions resulted in a group of six larger and increasingly global companies, now often referred to as the “Big 6,” that dominate hearing care worldwide. The companies that form the “Big 6” are Sonova, William Demant Holding (WDH), GN Store Nord, Sivantos (formerly Siemens), Starkey Hearing Technologies, and Widex.

Stage 3 also saw the movement of hearing aids into mass retail stores, such as Costco, Walmart, Sam’s Club (and now other mass retail outlets like large pharmacy chains) estimated by some to make up 20% of the overall hearing aid market by 2020.9 The Big 6 companies also began to invest in buying groups that had been established by independent hearing care professionals to reduce their purchasing costs. This allowed insight into independent practice and eventual control over some components of the market where there had been little influence in the past.

Initially very controversial due to state legal and licensing issues, the Internet was also found to be an innovative new distribution channel, attracting new customers in an otherwise stagnant market. These new Internet companies ranged from low-priced hearing aid sales’ operations with no support for customers, to businesses that encouraged customer interaction with “panel dispensers” across the country, available to provide fitting and follow-up support as part of the purchase.

The Focus period also heralded the beginning of forward integration by some of the Big 6, which served to increase corporate profits in the face of a stalled market for amplification, equipment, and other hearing care products. As in the auto industry, these new corporate retail acquisitions were often dispensing practices with owners who were retiring or in financial distress. Building upon their early success, forward integration spread to virtually all of the Big 6 hearing aid manufacturers.

Stage 4, or the Balance and Alliance phase, seems to have begun around 2011. Today, the hearing industry has been significantly consolidated and most manufacturers are working with big-box stores, some using their name brand (such as ReSound from GN Store Nord, Phonak from Sonova) and others using one of the “sister brands” purchased in the consolidation phase (such as Bernafon from WDH or Rexton from Sivantos). In this stage, some also own or have major financial interests in buying groups, such as American Hearing Aid Associates (WDH) and Audigy (GN). There are also myriad hearing-related Internet portals, including HearingPlanet (Sonova), HealthyHearing.com (WDH), and Audibene/Hear.com (Sivantos), that use a variety of innovative marketing and distribution techniques. This forward integration process has developed into a lucrative corporate profit center that even competes with their own-store customers like Connect Hearing (Sonova), HEARINGLife (WDH), HearUSA (Sivantos), Beltone (GN), and Audibel/All American Hearing (Starkey).Additionally, to further complicate the market picture, there are retail businesses that have been purchased by the manufacturers and allowed to keep their original names, operating procedures, and old employees—but they essentially operate as a corporate retail store.

Today, we are even seeing alliances between manufacturers and third-party insurance providers. For example, Twin Cities’ area manufacturer IntriCon has supplied United Health’s hi HealthInnovations with hearing aids since 2011.10 More recently, Sivantos purchased TruHearing, a third-party managed-care administrator of hearing aid benefits for managed-care plans.11 With intense competition within managed care and the desire for Medicare Advantage programs to offer hearing aid benefits, it’s likely we’ll see more of this type of activity. Perhaps even more disconcerting, online hearing aid and PSAP companies are attempting to get their feet in the door of this market as well.

Finally, while the above discussion has focused exclusively on hearing aids, it should also be noted that many of the Big 6 own separate entities that develop and manufacture audiologic/balance equipment, headsets, cochlear implants, FM systems, personal sound amplifiers, ALDs, sound-field equipment, and tinnitus remediation strategies.

Intense Competition as a Result of Industry Consolidation

Now that the hearing industry has gone through the natural business cycle evolution associated with industry maturation, patients are inundated with competitive marketing that presents numerous options about where to go for hearing care—and confuses them as to their best options for treatment. The 39% of independent practices9 who are left in this huge hearing care sandbox need to build a competitive castle using all the available information; we need to build a strategy that fits within the overall marketplace and within our respective communities. Part 2 of this series discusses a model of strategic competition that uses specific methods to gain intelligence on competitors. These methods will facilitate an understanding of how one practice compares to another and leads to the development of a strategic competitive plan in order to beat the competition in today’s marketplace.

Acknowledgement

This article was adapted with permission for HR from Chapter 3 of Dr Traynor and Robert G. Glaser’s new book, Strategic Practice Management: Business Considerations for Audiologists and Other Healthcare Professionals, Third Edition (Plural Publishing, 2018).4

PART 2: To read Part 2 of this article, please click here.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Dr Traynor at: [email protected]

Citation for this article: Traynor RM. Survival strategies in a competitive hearing healthcare market. Hearing Review. 2018;25(6):14-19.

References

-

Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VI: Factors Impacting Consumer Choice of Dispenser & Hearing Aid Brand; Use of ALDs & Computers. Hearing Review. 2002;9(12):14-23. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2002/12/marketrak-vi-factors-impacting-consumer-choice-of-dispenser-amp-hearing-aid-brand-use-of-alds-amp-computers/

-

Myers W. How to win in the midst of an industry consolidation. September 30, 2014. Available at: https://crownbiz.com/how-to-win-in-the-midst-of-an-industry-consolidation/

-

Bofah K. What is industry consolidation? September 26, 2017. Available at: http://www.ehow.com/facts_5965961_industry-consolidation_.html

-

Traynor RM. Competition in the audiology practice. In: Glaser RG, Traynor RM, eds. Strategic Practice Management.3rd Ed. San Diego,Calif: Plural Publishing;2018.

-

Foner E, Garraty JA. The Reader’s Companion to American History. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin; 1991.

-

Deans GK, Kroeger F, Zeisel S. The consolidation curve. Harvard Review.2002 [December]. Available at: https://hbr.org/2002/12/the-consolidation-curve

-

Kirkwood DH. Though the “Big Six” hearing aid makers are still intact, consolidation isn’t over in the hearing industry. September 27, 2011. Available at: http://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearingviews/2011/though-the-big-six-hearing-aid-makers-are-still-intact-consolidation-isnt-over-in-the-hearing-industry/

-

Strom KE. Slouching into the new millenium: 2001 brings little market growth to the hearing industry. Hearing Review. 2002;9(3):14-22.

-

Frazer G. The future of independent practice in audiology. Audiology Today.2017;29(4)[July]:56-61.

-

Strom KE. UnitedHealth enters hearing market: HR interviews hi HealthInnovations CEO Lisa Tseng, MD. Hearing Review. October 11, 2011. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2011/10/unitedhealth-enters-hearing-market-hr-interviews-hi-healthinnovations-ceo-lisa-tseng-md

-

Sivantos acquires TruHearing. Hearing Review. April 6, 2018. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2018/04/sivantos-usa-truhearing-enter-strategic-partnership

This is a fantastic comparison of the evolution of the hearing health industry to other industries.

As a 40 year veteran of the hearing industry, I am intensely focused on embracing disruptive technologies that benefit the consumer. I see nothing but opportunities for those who find the right niches.

I don’t know if you will be in Orlando for ADA next month, but if so, please stop by the SonicCloud booth. Fast Company just named us a top ten finalist for apps, not just in the Hearing app, or Health app category, but top ten among all apps created last year! Would love to share how we can assist your endeavors.

As a person who grew up around this business, (Father became a Beltone dealer in 1961) and have been a licensed hearing aid specialist for 35 years, I’ve noticed it’s not just the big box companies! Here in my hometown the ENT’s have become more aggressive! When I have referred paitients to them, including business cards, I rarely get them back! Also, because of state law, they do not have to charge sales tax! And they refused to give a client a prescription for hearing aids, so I had to charge sales tax, and ended up losing them to the Dr’s office!

I am trying to stay in this business but it’s getting tougher and more expensive every year! In fact, this may be my last year!