Practice Management | December 2012 Hearing Review

Practical guidelines for building the best team your practice can afford.

By Brian Taylor, AuD, and Gyl Kasewurm, AuD

Knowing when to hire another person for your practice is one of the most critical decisions an owner or manager will ever make. This is largely because the price of labor is high and relatively fixed. Experts generally agree that a business’ pre-tax profit needs to be at least 10% of total annual revenue before hiring another person for your staff.1 In other words, if you didn’t generate a 10% pre-tax profit in the last year, you probably need to hold your labor cost constant (and you don’t need to read any further until you’ve made your existing workforce more productive). However, if your pre-tax profit is 10% or more of your total revenue, then you can begin the process of hiring another person for your staff.

Objective Hiring/Hiring Objectively

|

|

| Brian Taylor, AuD, is director of practice development and clinical affairs for Unitron, and editor of the ADA’s Audiology Practices magazine. Gyl Kasewurm, AuD, is the owner of Professional Hearing Services, a private practice located in St Joseph, Mich. Correspondance can be addressed to Dr Taylor at: [email protected] | |

The two major reasons for bringing another person on board is generating more revenue (and profit) or lessening your own workload. The former represents a challenge surrounding the division of labor, while the latter signifies a change in your role within the organization akin to shareholder rather than practitioner/owner. Regardless of the specific reason, it is important that you’ve carefully evaluated the efficiency of your labor.

Once you know you can afford to hire another person, you need to carefully decide how this new staff member will contribute to the profitability of your business. Broadly speaking, there are three ways to divide your labor force (as characterized by Bob Wabler, former president of Amplifon USA):

- Staff who bring more patients to your practice through marketing. These are the “finders” within your practice;

- Staff who take care of the patients through consultative selling and clinical efforts. These are the “minders” in your practice; and

- Staff who take care of the essential back-office activities, such as phone scheduling, billing, and coding. These are the “grinders” in your practice.

Of course, in many practices the same person may play all three “finder-minder-grinder” roles simultaneously. And there are certainly times when you may want to contract with an outside agency or consultant for special projects or assignments.

If you are the owner or manager of your practice, some of the practical questions you need to ask yourself before adding to your head count include:

- Will you have more time to market your services and expand your business?

- Will bringing a new person on board allow you to dispense more products or serve more patients?

- Will you be able to give your patients more efficient service or quicker delivery, with the result that higher quality would lead to additional patients?

Unfortunately, there are few resources that offer guidance on when to hire and how to divide labor within a practice in order to improve productivity. The purpose of this article is to offer some insight and guidance on these important topics.

Believe it or not, running a profitable audiology or hearing aid dispensing practice has more in common with the National Football League than you might think. For about 20 years, the NFL has operated under a salary cap. The main objective of the salary cap is to control the costs of labor and ensure league parity (competitiveness) by requiring all teams to spend the same amount of money on its labor force, the football players. In 2012, each NFL team has about $120 million that they can spend on a roster of 53 players. If each player on the 53-man roster was paid equally, each would receive about $2.3 million per year. Of course, each player does not receive equal pay, as some positions are considered much more valuable, thus a considerably higher salary is warranted.

As previously mentioned, a salary cap enables teams to control costs. This helps prevent situations in which a club will sign a high-cost player in order to reap the immediate rewards of success now, only to later find themselves in financial difficulty because of those high costs as the player’s skills diminish over time. Without caps, there is a risk that teams will overspend in order to win now at the expense of long-term stability.

Salary caps incentivize teams to develop talent over time. This is more likely to lead to team stability, which is important for fans. No one wants to see their teams lose year after year or, worse yet, go completely out of business.

Like most other professional sports, a salary cap is something that is mandated by the NFL commissioner. Teams cannot choose to follow it. For teams that exceed the salary cap, there are severe penalties that could jeopardize the competitiveness of the team in future years.

Private businesses, on the other hand, don’t have the luxury of following a mandated salary cap to keep their labor costs in check. Even though they are not required to hold their costs under a salary cap, using “salary cap thinking” is an effective way to know when you can bring a new employee into the business and at what approximate pay grade.

What Is Your Salary Cap?

As a general statement, labor productivity is what powers sustainable businesses. This means that business owners must find the proper balance between what tasks the staff performs during the work day and what dollar amount the staff is paid to perform those tasks. In other words, you and your staff have to be busy, but you have to be busy doing the things that lead to optimizing revenue for your business over the course of a day, month, and year.

Regardless of how you specifically measure labor efficiency in your office, the idea of a salary cap is a great way to achieve business goals without overspending on the costs of labor. Let’s work through a simple example of how a practice owner might determine their salary cap using a couple of assumptions. As mentioned, most experts suggest that a business needs at least 10% pre-tax profit to be sustainable. This pre-tax profit is not used to pay salaries, but is set aside to reinvest in the infrastructure of the business or to cover expenses for a particularly poor month of low sales or high returns.

In addition, we know that the combination of hearing aid cost-of-goods and other expenses, including marketing, rent, and utilities, needs to be around 50% of gross revenue. These assumptions are shown in Table 1 for a practice that has been in existence for more than 10 years. (We chose $1 million because it is a nice round number, not because it represents any type of benchmark!) In this example, the owner, who happens to be an AuD-trained audiologist, has toiled for more than a decade building this practice from scratch and is faced with the knotty decision of whether to hire a recent AuD graduate from the local university, an experienced clinical audiologist with sales experience, or another assistant, or not hire anyone at this time.

|

Revenue |

$1,000,000 |

|

Direct costs, excluding labor (eg, cost of goods, |

($500,000) |

|

Gross Profit |

$500,000 |

|

Salary Cap (40% of revenue) |

($400,000) |

|

Total Expenses |

($900,000) |

|

Pre-tax Profit (10% of revenue) |

$100,000 |

|

Table 1. Financials from a private practice. |

|

By accounting for a pre-tax profit of 10% and all direct costs (excluding labor), we are able to get a clear idea of how much we can afford for labor before we make any hiring decision. In the Table 1 example, the salary cap is $400,000, which represents 40% of the total annual revenue of this practice. This is the amount of money the practice has to spend on labor, including the salary of the audiologist/owner.

In the ideal world, you may be tempted to bring on one or two more “star performers” (eg, an experienced, doctorate-level audiologist) to maintain this half-million dollars in gross profit, along with the expectation that the business will experience double-digit growth over time. The reality, however, is much different since each of those proven star performers is likely to command a premium salary of about $150,000 annually, plus benefits. (If we add the usual 33%-of-the-salary for benefits, that brings that salary to $199,500 per star.) The math in Table 1 dictates that we have to be extremely cautious in our hiring decisions.

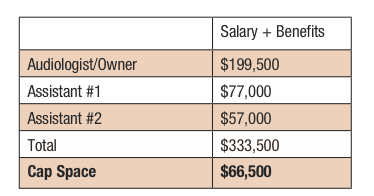

Let’s take a more careful look at the salary cap of this practice, which employs one audiologist/owner and two full-time assistants who are responsible for billing, coding, marketing, and answering the phone, among other necessary activities. Table 2 provides a breakdown of labor expenses relative to the salary cap. The available cap space tells us that this practice has $66,500 to spend on another staff member. Using the salary cap as the primary guide in making the decision to hire another professional, we realize that for this practice, there is a rather stark choice between three possibilities:

1) The first round draft choice. Hire that new AuD graduate who is a potential star performer at well below the market value. Under this scenario, the star performer would accept a salary + benefits of $66,500 with the expectation of growing the business over a finite period of time. This choice may be most appropriate, if the audiologist/owner wants to continue with her current work load, while continuing to grow the practice, and eventually transition out of the business.

2) The proven free agent with a high performance track record. Hire an existing star performer at current market value. Under this scenario, the proven star performer would command compensation of roughly $200,000 (salary + benefits). Since this is well over the salary cap, the audiologist/owner could choose to stop actively seeing patients or drop to part-time status, and receive a dividend from pre-tax profits rather than a high salary + benefits.

3) The free-agent utilityman. The third choice would be for the audiologist/owner to continue with their current workload and bring another assistant into the fold that could conduct some of the testing, follow-up with repairs, as well as other front office and back office duties. This person could be an audiology assistant who may be eligible to obtain a state license to dispense hearing aids.

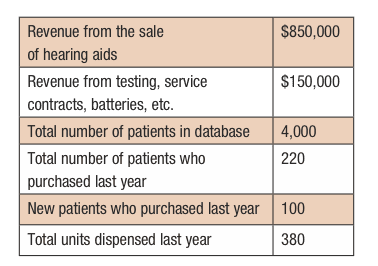

Now the numbers can be worked backwards to see how much labor is going to be needed to service those patients who generated $500,000 in annual gross profit. In order to know which hiring choice is best for you, let’s look at some other data from this practice in Table 3.

The real question is how many workers do you need to service 100 new patients and 220 experienced patients who repurchased, in addition to taking care of hundreds more of existing patients you are likely to see over the course of the year.

Let’s assume that it takes an average of 4.5 hours of time for 1 year to service new patients, and an average of 3 hours of time to service an experienced patient fitted with new hearing aids. For the 220 patients fitted with hearing aids, that’s 690 cumulative hours of the audiologist/owner’s time. Let’s compare these numbers to the capacity of each professional in your practice.

The Division of Labor

The key to staying under your salary cap is the judicious use of support personnel. After all, it is often the middling utility player who bails the star out of an ineffective performance by delivering a hit in crunch time! With a salary cap, your practice must rely on the utilityman to deliver in the clutch.

Support personnel within the practice (the free-agent utility player) must accept the role of jack-of-all-trades within the organization. In addition to conducting the essential work scheduling appointments, other duties may include hearing aid cleaning/trouble-shooting, conducting hearing aid orientation classes, and facilitating physician marketing campaigns. (Check with your state licensing board to see what licenses and credentials are needed to complete some of these tasks.) According to our calculations, each support staff has 1,840 hours available for the year to contribute to generating revenue by serving patients in various capacities.

Let’s turn our attention to the daily workload of the star performer. You might be wondering, “What is the maximum volume that the star performer can handle, or even should handle, before work quality starts deteriorating?” The answer to that question is not an easy one because it depends on the staff member. However, after almost 30 years of working with many different practitioners who have various years of experience, it has been our observation that dispensing professionals can suffer burnout if scheduled for more than 7 hours of direct patient contact per day during a 5-day work week. In a typical setting, after vacations, sick time, and “administration” time are taken into consideration, the dispensing professional has about 1,380 hours of clinical time per year to see patients (about 6 hours per business day).

In our scenario the audiologist/owner is using 50% of their clinical time to fit patients (1,380 total clinical hours/690 hours). Since the audiologist/owner still has about half of her time available to see existing patients for annual follow-ups, hearing screenings, etc, it probably doesn’t make sense to hire another star performer, unless the current owner is wanting to transition to shareholder status.

Fortunately, this practice has two ambitious support staff who can play the role of utilityman by providing a range of services for the practice. Therefore, this audiologist needs to be efficient with her time, rather than hire another star performer—even if that star decides to work for less than market value. Assuming the audiologist/owner wants to continue to see patients on a full-time basis, the decision to bring in a first-round draft choice or star free agent should be delayed until she is at 80% or more of full capacity seeing new and existing patients for hearing aid fittings.

Support personnel are being used successfully in a variety of practice settings, including the military, the VA, educational institutions, hospitals, industrial settings, and private practices. History has shown that the use of support personnel can be a tremendous asset to an audiology practice, both by improving productivity and by increasing profitability and patient satisfaction. It would seem that delegating tasks that do not require the education and expertise of a hearing care professional to support personnel would allow the professionals to see more patients, potentially generating more revenue—which should lead to increased profitability.

Just imagine how many more patients you could see if you didn’t have to clean hearing aids, complete order and repair forms, set up testing procedures, troubleshoot equipment, and teach patients how to clean, insert, and remove hearing aids. Not to mention demonstrating how to use remote controls, t-coils, LACE programs, loop systems, and other assistive devices. You could actually spend more time providing vitally needed services, such as family counseling, outlining realistic expectations, performing speech-in-noise testing, assessing central processing function, and developing relationships with your patients, as well as referring physicians.

Reality-based Practice

The decision to hire another staff member is never a capricious one. Regardless of the status of the employee you are targeting to bring on board—star free agent, first-round draft pick, or utilityman—both a salary cap and calculation of labor efficiency can be used to make a data-driven decision. Of course, the supply and demand of your local labor market, coupled with the overall pre-tax profitability of your practice, contribute to your hiring decision. As a general rule, however, the practitioner/owner should work to maximize the overall productivity of their existing staff before hiring another person.

References

1. Crabtree G. Simple Numbers, Straight Talk, Big Profits. Austin, Tex: Greenleaf Press; 2003.

Appendix

| Here is how the audiologist’s clinical time per year was calculated:

Total full time work days/year 260 (2080 work hours) Vacation days: 10 Professional leave (continuing ed.) 5 Sick Days: 5 National/State Holidays: 7 Personal time (emergencies): 3 (Total nonwork time): 30 days Total days available for work: 230 days 2 hours per day set aside for ‘administration’ for audiologist Available time = 230 days =1840 hrs/yr Billable time/day = 6/8 =1380 hrs/yr for audiologist For the support staff the day number of days available for work is 230 days Available time = 1840 hours/yr for support staff |