People with hearing loss think they understand more than they actually do, according to a new study on subjective intelligibility and hearing loss.

By Francis Kuk, PhD; Christopher Slugocki, PhD; Petri Korhonen, MSc

Hearing aid adoption, even in countries where hearing aids (HA) are provided for free, is less than 50%.1 This lower than desirable adoption rate may be due to stigma, poor performance, unnatural sounds, poor value proposition, cost, etc.2 In this article, we suggest that people with a mild-to-moderate degree of hearing loss may perceive less of a speech understanding problem than they really have as another reason for the low adoption rate.

We often hear people say, “perception is reality.” If a person perceives that s/he has no hearing problems, despite an audiogram that suggests a hearing loss and speech test results corroborating such observations, the person will likely not seek any help. At the other extreme, there are individuals who have a normal audiogram and speech test scores but perceive that they have a hearing problem. These people will likely not be satisfied with our answers that they do not have a problem. So, it is incumbent upon us as hearing care professionals (HCPs) to have an estimate of our client’s perception while we gather objective information on their hearing in order to better understand and meet their perceived needs.

Traditionally, HCPs measure speech recognition performance using tests such as the W-22, NU-6, QuickSIN, etc. In these tests, listeners repeat the words/sentences that they heard and the total number of words/sentences correctly repeated are tallied as the objective speech scores. Less commonly known, speech recognition scores can be measured by asking the listeners to estimate how much of the sentences/passages/words they understand using a 0- to 100-point scale (where 0 is not understanding any words and 100 is understanding every word). Speech scores measured this way are called subjective speech scores or perceptual speech scores.

Because subjective speech scores may be obtained more quickly, they were evaluated in the early 1990s as an alternative to objective speech testing in HA research.3 Cox et al reported that subjective speech scores were similar to objective speech scores when considering scores across groups of listeners. In the later 1990s and early 2000s Saunders and her colleagues measured listeners’ objective and subjective performance on the Hearing-in-Noise test (HINT) and noticed that some normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners show significant differences in performance between their subjective and objective HINT scores.4

Listeners whose subjective scores are better than their objective scores are called “over-estimators” of hearing ability. These individuals think they hear better than they actually hear. In general, these listeners also report fewer problems on hearing handicap questionnaires. On the other hand, listeners whose objective scores are better than their subjective scores are called “under-estimators” of hearing ability. These individuals think they hear more poorly than they actually hear. In general, these listeners report more problems on the hearing questionnaires. Saunders and Forsline recommended HCPs also measure subjective speech scores to determine if a listener is an over-estimator or an under-estimator for better counseling and for setting more realistic expectations for amplifications.5 More recently, Ou and Wetmore demonstrated that the QuickSIN may also be scored subjectively.6

Recently, we developed the Objective-Subjective Intelligibility Difference (OSID) test of interconnected sentences that reflect the contextual nature of daily communication.7 This new test overcomes some limitations in comparing objective and subjective speech scores using tests such as HINT or QuickSIN where the test sentences are independent and not thematically connected. Using the OSID test, we evaluated if hearing loss and HA use may affect objective and subjective scores differently.

The Objective-Subjective Intelligibility Difference (OSID) Test

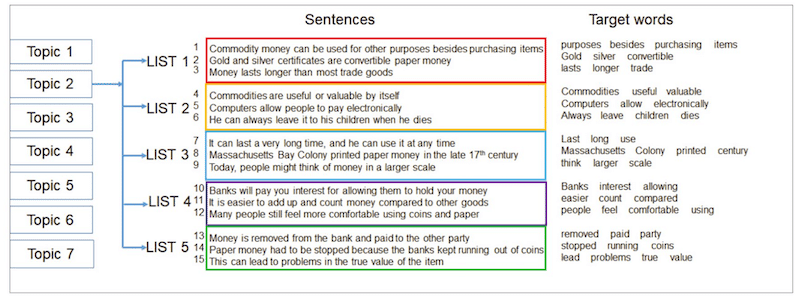

The OSID test was developed using the seven speech passages/topics available from the Tracking of Noise Tolerance (TNT) test.8 Each passage was made into 5 lists of 3 sentences per list with 3 to 4 target words per sentence or a total of 10 target words per list. Each list is to be used at one test for signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The same lists are available for use in objective and subjective testing (see Figure 1).

During objective testing, each sentence is presented one at a time and listeners are asked to repeat the sentences. Target words that are correctly repeated are scored. The percentage of target words that are correctly repeated in each list is reported as the objective score. During subjective testing, listeners rate how much of the list they understand after all three sentences within the list have been presented. Listeners use a number between 0 and 100 to reflect their understanding.

The speech sentences are presented at 75 dB SPL in the presence of a speech-shaped continuous noise presented from the front. Five SNRs (ranging between -10 to 15 dB) are used in order to estimate the intelligibility scores at each SNR. Objective testing is conducted prior to subjective testing using a different list.

Results of the OSID Test

Twenty-four normal-hearing (NH) listeners (mean age 64 years) and 17 hearing-impaired (HI) listeners (mean age 77 years) with a mild-to-moderate degree of hearing loss participated. These listeners have worn hearing aids for an average of 12.7 years. Both participant groups were tested in the unaided mode. The HI listeners were also tested with their own hearing aids.

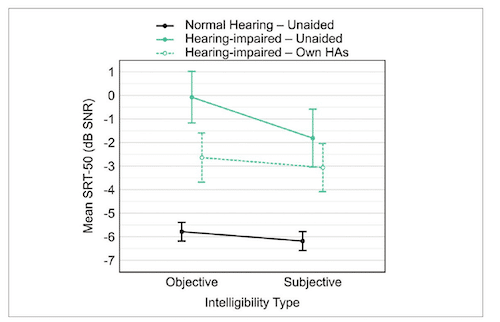

The individual subjective and objective scores of the listeners across SNRs (i.e., performance-intensity, PI functions) were transformed to a continuous function. The individual speech reception/recognition threshold at a 50% correct criterion (SRT50) were estimated from the functions. The average SRT50s for the NH, HI (unaided) and HI (own aid) are shown in Figure 2. Because SRT50 represents the smallest SNR to achieve 50% understanding, the smaller the number (or the more negative it is), the better is the performance.

Further Reading

Figure 2 shows that the NH listeners required a -6 dB SNR to reach SRT50 when the test was scored either objectively or subjectively. The HI listeners in the unaided mode required an SNR of 0 dB to reach the SRT50 when the test was scored objectively, but a -2 dB SNR when the test was scored subjectively (i.e., better). This difference between subjective and objective score was significant (p < 0.05). In the aided (own aid) condition, the average HI listener needed a -2.5 dB SNR for the objective SRT50 and a -3.0 dB SNR for the subjective SRT50. The difference between the subjective and objective SRT50 was not significant (p > 0.05) in the own aid mode. Differences in objective SRT50 among NH, HI (unaided), and HI (own aid) listeners were significant (p < 0.05).

Additional observations from Figure 2:

- The listeners’ own hearing aids improved their objective performance by about 2.5 dB. This suggests that modern hearing aids can improve the SNR of the listening environments even in a speech-front/noise-front configuration.

- On average, the subjective SRT50 of NH listeners is the same as their objective SRT50, suggesting that their perception of how much they understand is similar to how much they actually understand.

- For the average HI listener not wearing hearing aids, their subjective SRT50 is about 2 dB better than their objective SRT50, suggesting that they over-estimate their hearing ability or they think they understand more than they actually understand.

- For the average HI listener wearing hearing aids, their subjective SRT50 is <0.5 dB better than their objective SRT50. This non-significant difference suggests that properly fitted hearing aids narrowed the gap between subjective performance (perception) and objective performance (reality) in HI listeners.

- If one defines hearing aid benefit as the difference between the unaided and aided thresholds (i.e., SRT50), one can say that the HA benefit was 2.5 dB (0-(-2.5)) when measured objectively but 1 dB (-2-(-3)) when measured subjectively. It suggests that the average HI listener perceives less benefit from his/her hearing aids than s/he experiences!

These data suggest that HI listeners, when not aided, PERCEIVE LESS speech understanding difficulty than they experience. Making matters worse, when they are aided, they PERCEIVE LESS improvement in understanding than they receive.

Suggestions for HCPs to Meet Challenges

Clearly there are HI listeners who are accurate- and under-estimators of their hearing abilities. One does not have a priori knowledge of a listener’s perceptual tendency, but based on the results of this study, we will have to assume that the general HI population are over-estimators in our considerations.

1. Getting HI listeners to your office:

Obviously if one does not perceive a problem, one does not seek professional help. Thus, HCPs must make HI listeners aware that they have a problem and that solutions are available. This may be encouragement from spouses, relatives, friends, or primary care physicians. Or this could be news/knowledge from media outlets (including social media) linking hearing to other health issues (such as cognition). Some people may be responsive to free hearing screening or other incentives. Our profession must be innovative to create the opportunities for HI listeners to experience what they miss.

2. Determining if the listener is an accurate, over-, or under-estimator of hearing ability:

Our current best practice recommends objective testing of speech-in-noise ability. It does not discuss subjective testing of speech understanding. Thus, a crucial step is to include subjective speech intelligibility testing in our protocol to identify accurate-, under- or over-estimators for more personalized intervention. Interested readers can review the relevant references for subjective speech measurement using the Hearing-In-Noise test (HINT),4 the QuickSIN,6 or the Objective Subjective Intelligibility Difference test (OSID).8 Typically, a subjective SRT50 that is > 1.5 dB better than the objective SRT50 would suggest that the listener is an over-estimator whereas subjective SRT50 that is > 1.5 dB poorer than the objective SRT50 would suggest an under-estimator. A subjective SRT50 that is ± 1.5 dB of the objective SRT50 would suggest an accurate estimator of hearing ability.

3. What to do with over- and under-estimators?:

People who are over- or under-estimators of hearing abilities have mis-aligned their subjective and objective speech understanding. Thus, the first task is to make both groups realize this misalignment. One can then counsel these individuals to set the right expectations. This can be done by showing them their subjective and objective speech scores when there is more than 1.5 dB difference between the two measures.

For over-estimators, they should be told that they likely understand less than they think they do. While they may not perceive any problems, it is important to point out they do not know what they miss; but that there are consequences. For example, a lawyer who thinks they understand more than they do may misunderstand the intended message from the judge or their client and lose a case. A doctor who misunderstands their patients may miss a proper diagnosis with life-threatening consequences. The recent findings between hearing loss and cognitive decline should also be emphasized. The challenge with over-estimators is to get them to realize they have a hearing problem and to try amplification.

While the majority of unaided HI listeners are accurate and over-estimators, there are individuals (NH or HI) who are under-estimators. These individuals report a subjective SRT50 score that is at least 1.5 dB poorer than their objective SRT50. These individuals would not need any convincing that they have hearing difficulties. In contrast, they think they have more difficulties than what the speech test results show.

To set proper expectations, it is necessary to show these individuals that their objective speech scores are better than their subjective speech scores. When appropriate, indicate that their objective speech scores are comparable to (if not better than) individuals of similar ages and hearing status. The challenge with under-estimators is for them to accept a more realistic understanding of their hearing abilities and set proper expectations for amplification.

One of the reported characteristics of under-estimators is that they report greater hearing difficulties.4,5 Furthermore, they are less likely to be satisfied with hearing aids than those who are either accurate or over-estimators of their hearing ability.6 Thus, hearing aid selection for the under-estimators would require even more attention than those in the accurate- and over-estimation groups.

Assuming that satisfaction is solely tied to the acoustic performance of the hearing aids (which is a sweeping assumption, obviously), one should consider premium level hearing aids (and assistive technology as well) that are more likely to deliver a higher performance (audibility and SNR) improvement than lower tier products. It is also likely that more fine-tuning and follow-up sessions may be necessary for the under-estimators to be fully satisfied with the recommendations.

4. Important to demonstrate benefit:

The current results suggest that HI listeners as a group perceive less benefit subjectively (1 dB) than objectively (2.5 dB). Thus, HCPs must perform objective speech understanding measurement (pre- and post-fitting) as a means to maximize the demonstration of their successful fitting. Such benefit should be explained to the clients to further reinforce their confidence in the fitting. The observation in this study that HAs narrow the gap between subjective and objective speech understanding should be discussed with the clients as another motivation for/benefit of amplification.

In conclusion, HCPs should consider including objective and subjective speech intelligibility testing during a client’s visit in order to appraise if a listener may over- or under-estimate his/her hearing ability. This helps profile the client and allow the HCPs to set proper expectation and chart the right course of intervention for the clients. Doing so during pre- and post-fitting would also maximize the impact on the demonstration of hearing aid benefits.

You Might Also Like

About the Authors: Francis Kuk, PhD, is the director; Christopher Slugocki, PhD, is a research scientist; and Petri Korhonen, MSc, is a senior research scientist, at the WS Audiology Office of Research in Clinical Amplification (ORCA) in Lisle, Ill.

Photo: Dreamstime

References

- European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association. EuroTrak UK 2018. 2018. Available at: https://www.ehima.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EuroTrak_2018_UK.pdf

- Jorgensen L, Novak M. Factors Influencing Hearing Aid Adoption. Semin Hear. 2020;41(1):6-20. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1701242

- Cox RM, Alexander GC, Rivera IM. Comparison of objective and subjective measures of speech intelligibility in elderly hearing-impaired listeners. J Speech Hear Res. 1991;34(4):904-915. doi:10.1044/jshr.3404.904

- Saunders GH, Cienkowski KM. A test to measure subjective and objective speech intelligibility. J Am Acad Audiol. 2002;13(1):38-49.

- Saunders GH, Forsline A. Hearing-aid counseling: comparison of single-session informational counseling with single-session performance-perceptual counseling. Int J Audiol. 2012;51(10):754-764. doi:10.3109/14992027.2012.699200

- Ou H, Wetmore M. Development of a Revised Performance-Perceptual Test Using Quick Speech in Noise Test Material and Its Norms. J Am Acad Audiol. 2020;31(3):176-184. doi:10.3766/jaaa.18059

- Kuk F, Slugocki C, Korhonen P. Measuring objective and subjective intelligibility using speech materials from the Tracking of Noise Tolerance (TNT) test. J Am Acad Audiol. Published online August 18, 2023. doi:10.1055/a-2156-4393

- Kuk F, Slugocki C, Korhonen P. Performance of older normal-hearing listeners on the tracking of noise tolerance (TNT) test. Int J Audiol. 2024;63(6):393-400. doi:10.1080/14992027.2023.2223760