Research shows that certain types of EEG tests may help clinicians understand and treat schizophrenia with new approaches related to auditory processing.

Gregory A. Light, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry, and associate director of the UC San Diego Schizophrenia Program.

Researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine have published findings from two studies of EEG testing that may help diagnose and treat schizophrenia. One study article, published in the October 23, 2014 online edition of Schizophrenia Research, reports that schizophrenia patients don’t register subtle changes in reoccurring sounds as well as others and that this deficit can be measured by recording patterns of electrical brain activity obtained through electroencephalography (EEG). The article also describes a clinical EEG test that could be used to help diagnose persons at risk for developing mental illness later in life, as well as an approach for measuring different treatment options.

According to a second study article, published in the November 2014 online edition of NeuroImage: Clinical, there is a link between certain EEG test results and patients’ cognitive and psychosocial impairments, which indicates that the EEG test could be used to objectively measure the severity of a patient’s condition. The findings suggest that it might also be possible to alleviate some of the symptoms of schizophrenia with specialized cognitive exercises designed to strengthen auditory processing.

“We are at the point where we can begin to bring simple EEG tests into the clinical setting to help patients,” said Gregory Light, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego and a co-author on both studies. “We think it may be possible to train some patients’ auditory circuits to function better. This could improve their quality of life, and possibly reduce common symptoms of schizophrenia such as hearing voices.”

For one study, UC San Diego scientists and colleagues with the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia conducted experiments that involved monitoring volunteers’ electrical brain activity patterns as they listened to a sequence of beeps.

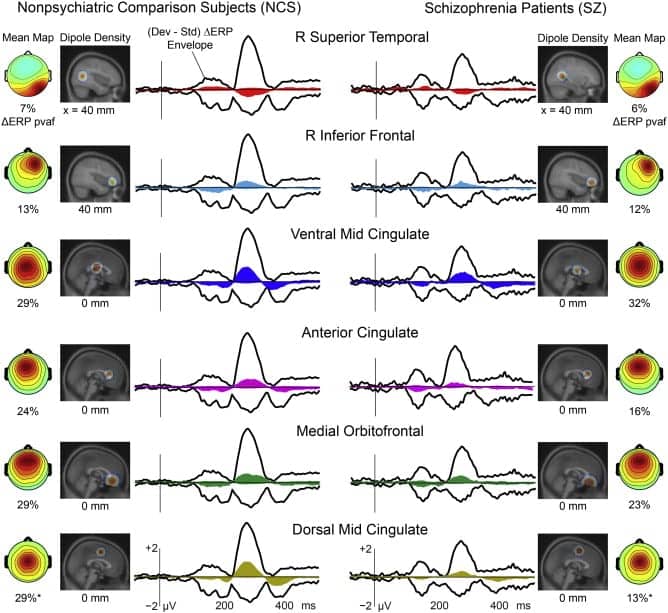

This figure shows patients’ auditory deviance response by percent variance accounted for (pvaf). The topographies, current dipole densities and percent variance (of the response difference) are accounted for, here separated into IC cluster subsets for the SZ and NCS subject groups, respectively.

A total of 1,790 people were tested at five sites nationwide as part of a National Institutes of Health-funded study to unravel the genetic basis of schizophrenia. The study participants included 966 who were schizophrenia patients, and 824 who were healthy control subjects.

The EEG data of this study were analyzed for two auditory processing metrics. The findings suggest that study participants with schizophrenia had a muted ability to detect and direct their attention to discordant beeps that had been introduced during testing.

In the second study, researchers showed that measures of MMN and P3a were associated with the severity of a patient’s symptoms and their day-to-day real-world functioning.

Researchers plan to use their findings from both studies to try to improve the quality of life for mental health patients.

“Our goal is to see if we can help people improve their brain functioning by providing daily cognitive exercises that are designed to sharpen their sensory information processing,” said Light. “We will then use EEGs to see if we can identify markers that predict which patients are most likely to benefit from this form of treatment.”

Sources: Schizophrenia Research, NeuroImage: Clinical, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine