Recent media reports have announced that several pharmaceutical companies are developing and testing drugs potentially capable of treating hearing loss, but the research and development teams often encounter difficulty demonstrating preclinical efficacy due to uncertainty regarding concentration of the medication at the intended delivery site to prove that it is responsible for observed changes in hearing.

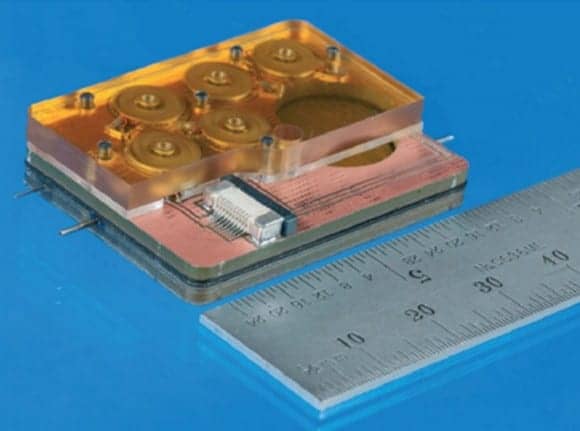

Draper, an independent not-for-profit laboratory in applied research, engineering development, education, and technology transfer based in Cambridge, Mass, reports that its engineers have collaborated with clinicians and scientists at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Ear to develop a tiny device capable of delivering drugs directly to the cochlea—an area of the inner ear difficult to reach with injections and systemic drug delivery. The new device also can be used to sample drug concentration in the cochlea, a key step toward securing approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

“Hearing loss drugs hold the potential to restore the natural sense of hearing, but preclinical measurements of drug concentrations in the inner ear will be critical in demonstrating that the drug is responsible for observed hearing changes prior to human trials,” said Jeff Borenstein, PhD, Draper’s principal investigator for the intracochlear drug delivery device.

Another approach used to deliver drugs that treat hearing loss is via injections through the middle ear, which is an avenue of indirect drug transport to the inner ear and may require repeat injections. Draper’s device, developed with funding from the NIH through its National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), utilizes precision instrumentation and microsystems in combination with expertise in the molecular biology and clinical aspects of hearing loss. The device from Draper can reportedly deliver one or more drugs in an automated, timed sequence directly into the fluid of the inner ear, and also has a reciprocating delivery cycle that keeps the volume of inner ear fluid constant while mixing in the drug, which is intended to increase the treatment’s safety and efficacy.

“Ultimately, this device should be useful for delivering drugs where and when they are needed, in a concentration where they can be effective, and without unwanted systemic side effects,” said Sharon Kujawa, PhD, director of audiology research at Massachusetts Eye and Ear. “Some of the most promising future treatments may require the delivery of combinations of drugs in a timed and sequenced manner to be effective, and these requirements will not easily be met with systemic delivery. With the local, intracochlear delivery provided by this device, it should be possible to take advantage of present and future breakthroughs in hearing loss treatment and prevention with the potential to benefit our patients with hearing loss.”

Borenstein and Kujawa have published results of their recent work in the peer-reviewed journal Lab on a Chip. They note that in addition to improving confidence in results from preclinical trials, a wearable version of the drug delivery device could be available in the near future to treat patients who experience hearing loss as a side effect of medications like cisplatin, a chemotherapy drug, or tobramycin, which is used to treat cystic fibrosis.

Source: Draper

Image credits: Draper; CMIT; Massachusetts Eye and Ear