Expert Roundtable | September 2015 Hearing Review

Chapter 2: Adding cognitive function changes the fitting paradigm

Note: This is the second article in a seven-part special Expert Roundtable series published in the September 2015 edition of The Hearing Review, guest-edited by Douglas Beck, AuD. For all the articles in this Expert Roundtable, click here.

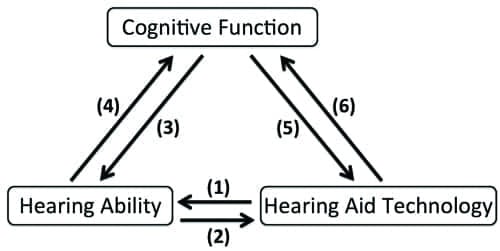

The complexity with which we consider patient needs and benefit from treatment has increased over the past decade through the added consideration of cognitive function. To fully understand patient treatment, we must now consider the relationship between cognitive function and hearing ability and the relationship between cognitive function and hearing aid technology.

Historically, the approach to understanding the needs of patients with hearing loss and their treatment has been focused on the relationship between hearing ability and hearing aid technology (Figure 1a). Hearing ability and hearing aid technology can affect each other, as discussed below.

(1) Hearing Aid Technology ? Hearing Ability

Figure 1a. The traditional focus of hearing care has been to understand the needs of patients with hearing loss, with treatment focused on the relationship between hearing ability and hearing aid technology.

There is no doubt that hearing aid technology significantly affects a patient’s hearing ability, most notably increasing audibility and improving speech understanding. Some effects of technology on hearing can be difficult to quantify, such as the impact of technology on spatial hearing, pitch perception, and other complex auditory functions.

(2) Hearing Ability ? Hearing Aid Technology

Figure 1b. However, with the addition of cognitive function, we’re now adding a new level of complexity and interaction in hearing healthcare.

Hearing ability, as measured by the audiogram, grossly reflects the hearing ability of an individual and grossly indicates the benefit a patient may receive from amplification for simple speech stimuli in quiet. The audiogram is a poor predictor, however, of a patient’s ability to understand speech in noise.1 Further, the audiogram is a poor predictor of the benefit patients will receive from advanced hearing technology in complex listening situations.2 Therefore, the need to fine-tune hearing aid technology to the unique needs of each individual is apparent.

Recently, findings addressing “hidden hearing loss” suggest that those with greater hidden hearing loss could have significant deficits to the coding of sounds in the periphery,3 which potentially limits the benefit provided by hearing aid technology.

The complexity with which we consider patient needs and benefit from treatment has increased over the past decade through the added consideration of cognitive function. This change to the patient landscape is reflected in Figure 1b. To fully understand patient treatment, we must now consider the relationship between cognitive function and hearing ability and the relationship between cognitive function and hearing aid technology.

(3) Cognitive Function ? Hearing Ability

Cognitive function affects hearing ability in very direct ways. For example, the ability to focus attention on different talkers in a crowded room is one top-down benefit that cognitive function provides to hearing ability. That is, knowing where to focus one’s attention in a crowded acoustic landscape is an important attribute.

(4) Hearing Ability ? Cognitive Function

Less obvious is the fact that hearing ability can affect cognitive function. McCoy et al4 demonstrated that hearing loss can degrade memory ability by increasing the load on working memory (WM). WM is responsible for information processing and memory storage/retrieval. WM has limited resources, however. Therefore, as more resources are required to interpret sound, fewer resources are available for other cognitive functions.

Lin5 has suggested that hearing loss may result in accelerated cognitive decline. Of note, it may be that hearing loss and cognitive ability degrade together because of a common cause, such as poor cardiovascular function. Additional research is necessary to determine whether or not hearing loss is the cause of accelerated cognitive decline.

(5) Cognitive Ability ? Hearing Aid Technology

Evidence is growing that the cognitive ability of a patient affects the benefit they receive from hearing aid technology. Lunner and Sundewall-Thoren6 found that the level of someone’s cognitive ability determined whether they would benefit more from fast or slow-acting compression. Cognitive ability can be a better predictor of hearing aid benefit to speech understanding in complex listening environments than the audiogram, where cognitive function is necessary to separate the talker from other simultaneous talkers and focus attention on that target speaker.7

(6) Hearing Aid Technology ? Cognitive Function

Figures 2a. In the past, much of our research and amplification strategies have focused on speech intelligibility and sound quality.

Recent breakthroughs in research have demonstrated that hearing aid technology can have a beneficial impact on the cognitive function of the hearing aid wearer. In 2014, Desjardins and Doherty8 demonstrated that hearing aid noise reduction can reduce cognitive load, making listening to speech in noise easier for the hearing aid wearer even if speech understanding isn’t improved. Reduction in listening effort over a period of time can have the effect of reducing listening fatigue,9 a problem experienced by many people with hearing loss because they have to concentrate more to follow conversations in a noisy environment and are more mentally exhausted as a result.

With technology starting to focus on better spatial hearing by hearing aid wearers, research has also found that access to spatial cues allows the listener to segregate talkers and focus on the target talker better, reducing listening effort even when speech understanding doesn’t improve.10

Figure 2b. Today, we are now adding a third dimension: the cognitive impact on the hearing aid user. When combined with the more complex patient landscape of Figure 1a-b, what should emerge is a better understanding of the patient with hearing impairment and a more nuanced picture of their technology needs.

These results and others help us understand how hearing ability, hearing aid technology, and cognitive function are all tied together. While we used to describe benefit from technology in two dimensions, focusing on whether and how much a technology affects sound quality and speech understanding (Figure 2a), we now can describe the benefit that technology provides in three dimensions (Figure 2b). This view of hearing aid benefit combined with the more complex patient landscape of Figure 1b enables us to better understand the needs of people with hearing loss and how to better treat them with technology.

References

-

Houtgast T, Festen JM. On the auditory and cognitive functions that may explain an individual’s elevation of the speech reception threshold in noise. Int J Audiol. 2008;47(6):287-295.

-

Edwards B. The future of hearing aid technology. Trends Amplif. 2007;11(1)[March]: 31-45. doi: 10.1177/1084713806298004

-

Plack CJ, Barker D, Prendergast G. Perceptual consequences of “hidden” hearing loss. Trends Hear. 2014;9[Sept]18. doi: 10.1177/2331216514550621

-

McCoy SL, Tun PA, Cox LC, Colangelo M, Stewart RA, Wingfield A. Hearing loss and perceptual effort: downstream effects on older adults’ memory for speech. Q J Exp Psychol A. 2005;58(1):22-33.

-

Lin FR. Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(10): 1131-1136.

-

Lunner T, Sundewall-Thoren E. Interactions between cognition, compression, and listening conditions: effects on speech-in-noise performance in a two-channel hearing aid. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18(7):604-617.

-

Rudner M, Foo C, Ronnberg J, Lunner T. Cognition and aided speech recognition in noise: specific role for cognitive factors following nine-week experience with adjusted compression settings in hearing aids. Scand J Psychol. 2009;50(5):405-418.

-

Desjardins JL, Doherty KA. The effect of hearing aid noise reduction on listening effort in hearing-impaired adults. Ear Hear. 2014;35(6):600-610.

-

Hornsby BW. The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands.” Ear Hear. 2013;34(5): 523-534.

-

Xia J, Nooraei N, Kalluri S, Edwards B. Spatial release of cognitive load measured in a dual-task paradigm in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. J Acoust Soc Am. 2015; In press.

Brent Edwards, PhD, is a long-time researcher in the hearing care field and serves as vice president of EarLens, Menlo Park, Calif.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or [email protected]

Original citation for this article: Edwards B. Adding cognitive function changes the fitting paradigm. Hearing Review. 2015;22(9):16.

This article is one of seven chapters in a series of articles that review the key points addressed during the 2015 AudiologyNOW! session titled “Issues, Advances, and Considerations in Cognition and Amplification.” Follow the links to related chapters by Douglas L. Beck, PhD, Christian Füllgrabe, PhD, Gabrielle Saunders, PhD, Jason Galster, PhD, Andrea Pittman, PhD, and Gurjit Singh, PhD.