By Marshall Chasin, AuD

During this time of Covid, we haven’t been able to attend live concerts, symphonies, or opera events. While musicians are just now beginning to perform live for the first time in months, if not years, the question arises about the dynamics (loud/soft features) of loud music. There is something “enlivening” about actually being there rather than just listening to recorded music. But it’s not as simple as just turning up the volume to “imagine that I was there.” And this goes for speech as well as music.

Related article: Plural Publishing Releases ‘Music and Hearing Aids’

It is true that the dynamics of speech are important where consonants are soft and vowels are… louder, but not nearly as important for music, where changes from soft to loud impart not only the musical notes that are being played or sung, but emotion and subtleties that can easily be missed on recorded music.

One cannot assume that loud music is merely music where the volume has been turned up. Increasing a volume control knob would turn up the low-frequency sound and the higher frequency sound equally, but that is not what happens with louder music (or even with louder speech).

But first, speech:

In all languages of the world, speech is made up of low-frequency sonorants (vowels, nasals, and liquids) which are at a higher sound level than the high-frequency obstruents (fricatives, affricates, stops, and clicks). As a “summary,” the long-term average speech spectrum is typically shown in textbooks as having its greatest energy in the 400-500 Hz region (around the first formant F1) with a 5-6 dB/octave fall-off above that. However, for louder speech, the low-frequency sonorants grow much more than the higher frequency obstruents. One cannot simply utter a loud ‘s’ as in “silly” as one can (and does) utter a loud vowel, in conversational speech. That is, as speech gets louder, the lower frequency sounds increase much more than the higher frequency sounds.

And now for music:

Unlike speech, as the music is played at a louder level, for brass and woodwinds, the higher frequency harmonic components increase in loudness much more than the lower frequency fundamental energy; it is the opposite of speech. In fact, for woodwind instruments and brass instruments, the lower frequency fundamental energy barely increases as the playing level increases. This is shown in Figure 1 (above) for a clarinet playing a note softly (pianissimo) and loudly (fortissimo).

But for stringed instruments (whether amplified or not), as the playing level increases, there is a well-defined balance that is maintained between an equivalent low-frequency sound level increase and a high-frequency sound level increase. For stringed instruments, simply turning up the volume will be identical to listening to that music played at a louder level.

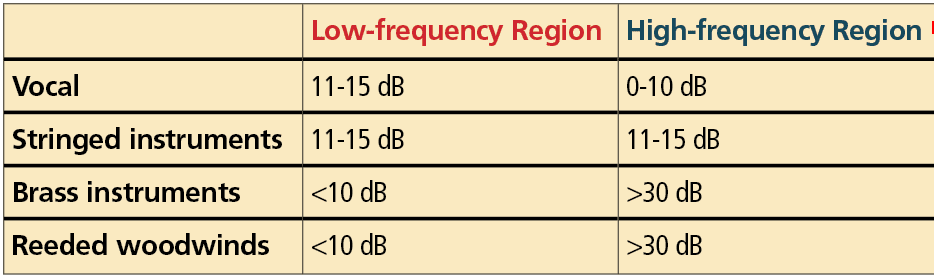

Table I is a summary of the spectral balance changes for speech and for various types of music as the playing (or speaking) level is increased. This has ramifications for setting a “music program” for live and for recorded music. For recorded music, especially since this has typically already been compression limited once during the recording phase, the settings should be more linear in order to prevent double compression from taking place, but otherwise, in terms of gain and output, be similar to a speech-in-quiet program. For live music, however, it is a much more complex task, where less high-frequency amplification may be required than that specified for a speech program except for string-heavy, live classical music.

Acknowledgements: Figure and Table used with permission from Chasin, Music and Hearing Aids, Plural Publishing—due out in March 2022.

Citation for this article: Chasin M. Loud live music versus loud recorded music Hearing Review. 2022;29(4):10.

Marvellous insight and science, as always, from Prof Chasin. Looking forward to his new book, to glow alongside Prof Nina Kraus’ “Of Sound Mind”.

Equipped with that and Prof Chasin’s earlier articles, I began a most constructive dialogue with my audiologist.

She freely admits that her training is all about speech and very little about music – whether for enjoyment or work (both, in my case).

So she persisted – enthusiastically – with a rather daunting manufacturer’s interface and has given me remarkably natural hearing: down to 40 Hz (amazing!) and up to my limit of 4 kHz – but not beyond, thus remedying compressor-pumping on high energy harmonics. She’s removed the too-clever algorithm stuff, frequency shifting, directionality, multi band comping… and simply activated a broadband ‘brickwall’ comfort limiting. Much as I use in my day to day recording

Of course, everyone’s hearing is unique but in my case I can not only enjoy and work with music once again but actually understand speech much better. Nuances restored! Less can be more!

Excellent explanation of loud (low) and soft (high) frequency sounds.