Tech Topic | January 2023 Hearing Review

Those who are living with hearing loss experience difficulties in many aspects of their lives, including understanding and following instructions.

By Jackie L Clark, PhD

On occasion, patient engagement in the audiology clinic can provide times of puzzlement, deep reflection, and sleepless nights.

For example, sixty-five-year-old Ms B has been wearing hearing aids for a few months. However, today she urgently returned to the audiology clinic with a concern that things didn’t seem right, and she was unable to get her hearing aid out of her left ear last night.

Before going in to visit with Ms B, a review of the clinical notes from the initial evaluation and subsequent hearing aid fitting did not yield anything out of the ordinary. Patient-centered care (PCC) and best practices (BP) in audiology strongly suggest that verification and validation of hearing aids are part of the procedures undertaken during audiological hearing aid fitting.1 Not only do these measures reduce the number of hearing aids returned for credit while increasing patient satisfaction, but also reduce professional liability with patient claims regarding the audiologists’ ethical standards of abiding with BP in hearing aid fittings.

A review of the clinical notes from the fitting confirmed that targets were matched as verified through Real Ear Measurement and aided soundfield testing and were validated with a patient satisfaction survey one month post-fitting. It was also noted on the day of the hearing aid fitting that Ms B indicated assent of understanding of hearing aid care and maintenance, as well as demonstrating successful insertion and removal of each hearing aid and hearing aid batteries at least twice during the fitting appointment.

Given the scenario above, a multitude of questions and possibilities emerge…Perhaps Ms B has had a change in hearing in one or both ears? Perhaps she has cerumen occlusion in either ear canal or the receiver(s)? Perhaps the new hearing aid needed slightly more gain in some frequencies within the speech spectrum. And of particular interest, was Ms B experiencing some degree of cognitive decline while attempting to remove her hearing aids? Or perhaps, were there missed clues about Ms B’s aided audibility during the hearing aid orientation/fitting appointment? Perhaps Ms B’s brain was challenged with acclimatization to the new hearing aids during the orientation portion of the hearing aid fit and is now in need of additional aural rehabilitation?

Dementia and Neurodegenerative Conditions

Dementia is typically considered a progressive deterioration and refers to a cluster of symptoms ranging from memory loss; difficulty concentrating, planning, or organizing; confusion and needing help with activities of daily living (ADL); problems with language and understanding; and changes in behaviors. A report by the US Department of Health and Human Services2 on the typical profile of elder adults with dementia and their caregivers suggest that 63% of adults with dementia were 80 years old and older. Reportedly, older adults with less than a high school education are significantly more likely to have dementia than older adults with more education. More importantly, the report suggests that individuals with dementia are more likely to require assistance with self-care, mobility, and household activities than those age-matched without dementia. Unfortunately, the current statistics on dementia are conservative simply because individuals with mild or early stages of cognitive decline are often missed and unlikely to be classified in large-scale reports. It is important to recognize that these U.S. data also show that cognitive decline is not limited to the geriatric population. In fact, Early Onset Dementia (EOD) has been identified in adults in their early 30s to early 60s with symptoms varying from memory problems to difficulties understanding visual images or spatial relationships. It is estimated that the incidence of EOD is 12.6 per 10,000 adults in the US3 and in Italy 13 per 10,000 adults.4 Neurodegenerative declining conditions that ultimately have a negative secondary impact in the way of slow and insidious behavioral changes as the neurodegenerative process slowly evolves over decades. Or in the case of the rapidly deteriorating neurodegenerative condition, Lewy-Body Dementia/Disease, a precipitous evolution of extreme behavior changes could unfold within 5-7 years of diagnosis.

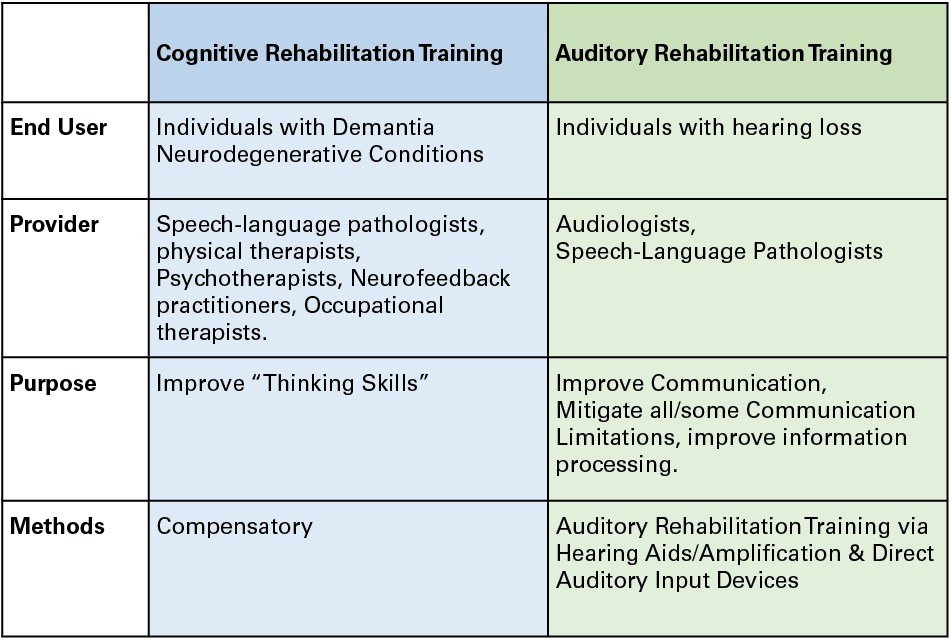

Cognitive Rehabilitation Training/Therapy (CRT)

Regardless of the etiology associated with cognitive decline or cognitive changes, Cognitive Rehabilitation Training/Therapy (CRT) is frequently called for. CRT is neither a treatment nor a cure. Professionals, such as speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, psychotherapists, neurofeedback practitioners, or occupational therapists are trained to choose an appropriate program for individuals who have experienced traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, or neurological disorders. In a simplistic analogy, CRT is considered training involving “thinking skills” aiming to restore or help the affected person compensate for loss of cognitive function through behavior or environmental modifications by identifying behavioral strategies or environmental modifications needed to achieve goals within daily living activities. Restorative skills training might be called for and is based on neural “plasticity” to facilitate behavior modifications.

Hearing Loss

In a prevalence study of hearing loss among US adults,5 which reported an increasing number of the general adult population experiences hearing loss in tandem with aging. Consequently, it would be expected that when there is motivation, perception of a handicapping condition due to hearing loss, as well as identification of sensorineural hearing loss, the primary goal would aim towards holistic fitting appropriate technology (e.g. hearing aid amplification, FM systems, Digital Remote Microphones, Assistive Listening Devices, TeleCoil and TeleLoop systems, AirPods and other direct auditory input devices, etc). Beck,6 reported that Apple has sold nearly 100 million AirPods. He hypothesized the reason their sales are 20 times larger than traditional hearing aids (in the USA) is largely due to the vastly improved signal-to-noise ratio, the overall sound quality, ease of connectivity to phones and other devices, and reduction of background noise.

Those who are living with hearing loss are also experiencing difficulties in many aspects of their lives: understanding and following physicians’ instructions, engaging in intimate conversations, appear to be uninterested in social interactions, following directions or instructions that are expressed orally, hearing and responding to weather alerts and other warning sounds such as sirens, localizing and/or hearing origins of unexpected sounds in their immediate vicinity, etc. In addition to the auditory difficulties, older adults often present a challenge in the ease of adopting technology due to some predicted visual-spatial abilities, dexterity, and reasoning or judgement challenges. Social isolation that often accompanies hearing loss in older adults may result in loneliness, depression, and symptoms of cognitive decline. Kricos7 aptly demonstrated that confusion caused by poor audibility from hearing loss is easily confused for dementia and vice versa.

Published research has focused on social isolation exacerbated by hearing loss in the elderly adult population. Lin8 has substantiated that the likelihood of identification of significant hearing loss also comes with an association with cognitive decline in adults older than 60 years. In fact, the data supported the supposition that hearing loss may be “causally related to dementia, possibly through exhaustion of cognitive reserve, social isolation, environmental differentiation or a combination of these pathways.” Pichora-Fuller et al9 also investigated the deleterious impact on older adults with near-normal hearing who experience more listening difficulties than young normal-hearing adults when listening to speech in the presence of background noise. Fuller interpreted the findings as supporting a processing model that would reduce the reallocation of processing resources (re: Lin’s term “cognitive reserve”) used to support auditory processing when more difficult listening situations occur for older adults. Though the mechanisms for neurodegenerative disorders and hearing loss differ, both conditions result in deteriorating social networks and social isolation.

Auditory Rehabilitation Training (ART)

Aural Rehabilitation Training (ART) has significantly changed since its early beginnings with American troops who suffered hearing loss during and following World War II. Professionals currently engaged in ART are audiologists and speech-language pathologists. It is not unusual for individuals with new or re-programmed hearing aids to not achieve optimal success in communication immediately and to require a period of acclimatization for the auditory system to adapt to the new auditory technology. The primary mission of ART is to guide the individual with hearing loss through strategies for improving receptive and expressive communication, speechreading, and potentially skills learning to actively mitigate some or all the limitations experienced due to hearing loss for them to engage in their community.

Continuation of Ms B’s Case:

Upon cursory otoscopic inspection of Ms. B’s ear canals, two #312 batteries were encased in cerumen between the somewhat reddened bony and cartilaginous portion of the left auditory canal.

Nonetheless, vexing questions remain with potential solutions to explore:

Q1: Could Ms B have misunderstood (earlier in the appointment) which device was the hearing aid and which was the battery due to lack of adaptation to the new hearing aids during the orientation phase of the hearing aid fitting?

Potential Solutions

• Perhaps providing more visual aids

• Perhaps more insertion/removal practice sessions at the initial fitting or subsequent visits

• Use a “teach back” method or patient demonstration of skills

Q2: Could Ms B be experiencing cognitive decline? Has she become confused about where the hearing aid batteries and hearing aids are placed?

Potential Solutions

• Identify a friend, family member, concierge therapist/staff member who can periodically check on Ms. B’s acclimatizing to the new hearing aids

• Refer Ms B to a Speech Pathologist or Occupational Therapist to work more intensely with strategies and compensatory skills of hearing aid maintenance and management

After the audiologist removed the hearing aid batteries from the left ear canal, Ms B was referred to an otolaryngologist to ascertain whether medical management was necessary because of the prolonged stay of multiple hearing aid batteries in her left ear canal. Additional hearing aid orientation counseling by Ms. B’s audiologist, as well as a cognitive screening, were undertaken, and she was referred back to her family doctor for further evaluation due to a non-normative result. Without a doubt, Ms. B’s audiologist deeply regretted not deploying a cognitive screen as part of the audiological evaluation so that the initial missteps in rehabilitation might have been avoided. After all, cognitive screening is considered part of the audiologist’s scope of practice and, therefore, deployable during any audiological evaluation.

Shen et al10 suggested that for older clients who have cognitive decline consider using hearing aid technology with automatic features (ie, directionality, program change, telecoil, etc.) in order to reduce cognitive load for the wearer; provide clear and brief instructions while also making frequent visits for reinforcing new skills with the technology; set realistic expectations of patients (and their families) about amplification technology benefit; encourage the patient and their families as well as friends to use good communication strategies diligently; refer for cognitive rehabilitation while offering auditory rehabilitation.

Clinical audiologists are very familiar with longer, more detailed appointments that allow for a dedicated in-depth case history, extensive diagnostic testing, with detailed counseling times. When combined, the extensive time spent with each patient brings opportunities to discuss communication abilities and difficulties. Consequently, cognitive screenings are wholly appropriate for audiologists to employ to ensure their patients will ultimately maximize their communication skills. Since audiologists would be more likely to encounter patients with behaviors consistent with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in a typical clinic day, it is important to choose a validated pen and paper or electronic Cognitive Screening method that is easy for the patient to engage with as well as capture potential MCI by accurately tapping into the range of cognitive abilities: visuospatial, attention, working memory, language, short term memory, and executive function. Once completed, each patient’s long-term care plan will be improved with greater patient-centered care and accuracy, and ultimately, their quality of life will be improved.

Citation for this article: Clark JL. Hearing aid batteries were WHERE??? Hearing Review. 2022;30(1):16-18.

References

- Jorgensen LE. Verification and validation of hearing aids: Opportunity not obstacle. J Otol. 2016;11(2):57-62.

- US Department of Health and Human Services report. A profile of older adults with dementia and their caregivers. ASPE Issue Brief. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//186646/DemChartIB.pdf. Published September 2018.

- Blue Cross Blue Shield report. Early onset dementia and Alzheimer’s rates grow for younger Americans. https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/file-attachments/health-of-america-report/HOA-Dementia.pdf. Published February 27, 2020.

- Chiari A, Vinceti G, Adani G, et al. Epidemiology of early onset dementia and its clinical presentations in the province of Modena, Italy. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2021;17(1):81-88.

- Agarwal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1522-1530.

- Beck DL. Beyond the audiogram – Whole brain hearing and listening. ASHA Leader. https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/leader.FTR2.27112022.aud-assessment-sin.44/full/. Published November 15, 2022.

- Kricos PB. Audiologic management of older adults with hearing loss and compromised cognitive/psychoacoustic auditory processing capabilities. Trends in Hearing. 2006;10(1):1-28.

- Lin FR, Metter J, O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68 (2):214-220.

- Pichora-Fuller MK, Schneider BA, Daneman M. How young and old adults listen to and remember speech in noise. J Acoust Soc of Am. 1995;97(593).

- Shen J, Anderson MC, Arehart KH, Souza PE. Using cognitive screening tests in audiology. American Journal of Audiology. 2016;25(4):319- 331.