By Michelle Ma, Associate Director, University of Washington News

Editor’s Note: The following sentence, “The Navy is set to implement a 75% increase in air activities over the Olympic Peninsula” has been clarified to read “The Navy is set to implement a 62% increase in airborne electronic warfare and 13% increase in air-to-air combat training over the Olympic Peninsula,” as requested by Lauren Kuehne, the researcher quoted in the article.

An area in the Olympic Peninsula’s Hoh Rain Forest in Washington state for years held the distinction as one of the quietest places in the world. Deep within the diverse, lush, rainy landscape the sounds of human disturbance were noticeably absent. But in recent years, the US Navy switched to a more powerful aircraft and increased training flights from its nearby base on Whidbey Island, contributing to more noise pollution on the peninsula — and notably over what used to be the quietest place in the continental US. While local residents and visitors have noticed more aircraft noise, no comprehensive analysis has been done to measure the amount of noise disturbance, or the impact it has on people and wildlife.

Related article: Army Researchers Examine Methods of Rotocraft Noise Reduction

Now, as the Navy is set to implement another increase in flight activities, a University of Washington study provides the first look at how much noise pollution is impacting the Olympic Peninsula, according to an article on the UW News website.The paper found that aircraft were audible across a large swath of the peninsula at least 20% of weekday hours, or for about one hour during a six-hour period. About 88% of all audible aircraft in the pre-pandemic study were military planes.

“I think there is a huge gap between what the Navy is telling people — that its aircraft are not substantially louder and operations haven’t changed — and what people are noticing on the ground,” said lead author Lauren Kuehne, who completed the work as a research scientist at the UW School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences and is now an independent consultant. “Our project was designed to try and measure noise in the ways that reflect what people are actually experiencing.”

The study was published Nov. 25 in the journal BioOne Complete.

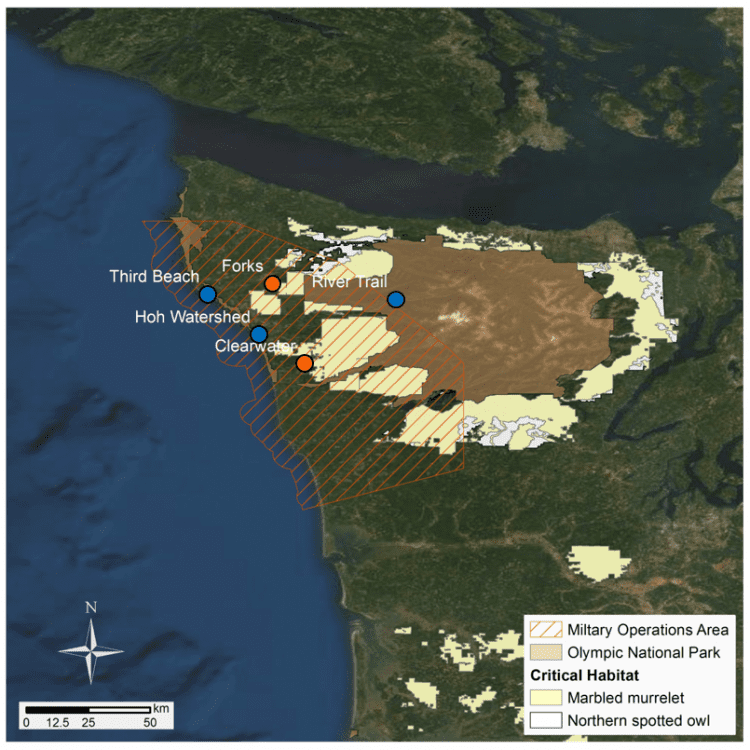

The Navy is set to implement a 62% increase in airborne electronic warfare and 13% increase in air-to-air combat training over the Olympic Peninsula, a place that is historically, culturally, and ecologically significant. Eight American Indian tribes call the peninsula home, while Olympic National Park receives more than 3 million visitors a year and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. More than two dozen animal species are found only on the peninsula, and multiple species are listed as threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act.

“The Olympic Peninsula is a renowned hotspot for wildlife, home for people of many different cultures, and a playground for outdoor enthusiasts,” said co-author Julian Olden, professor at the UW School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences.

The researchers chose three primary sites on the Olympic Peninsula to monitor the soundscape during four seasonal periods from June 2017 to May 2018. Two sites, at Third Beach and Hoh Watershed, were near the coast, while the third site was inland on the Hoh River Trail. They placed recorders at each site to capture sound continuously for 10 days at time, then recruited and trained volunteers to help process the nearly 3,000 hours of recorded audio.

“This data is very accessible — you can hear and see it, and it’s not rocket science,” Kuehne said. “I wanted people to feel like they could really own the process of analyzing it.”

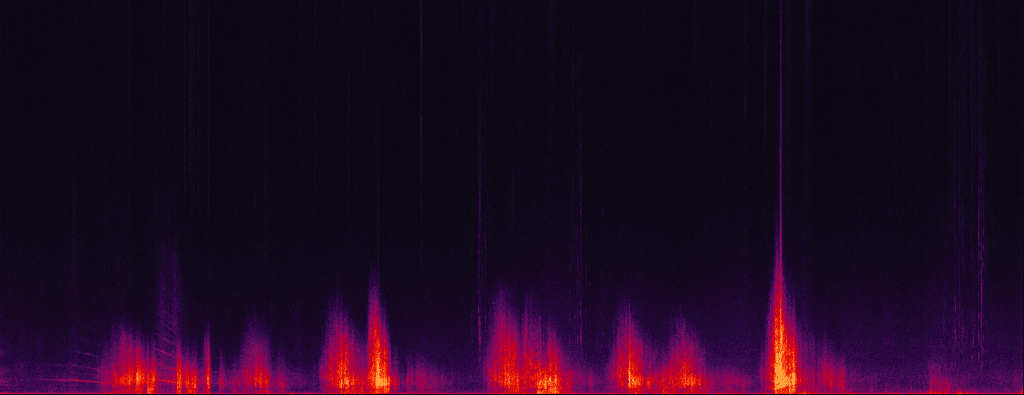

From their analysis, the researchers identified nearly 5,800 flight events across all monitoring locations and periods. Of these, 88% were military aircraft, 6% were propeller planes, 5% were commercial airplanes, and less than 1% were helicopters. Three-quarters of all recorded military aircraft noise occurred between 9 am and 5 pm on weekdays. Most of the military aircraft were Growlers, or Boeing EA-18G jets that are used for electronic warfare — drills that resemble “hide and seek” with a target.

The researchers found that most of the aircraft noise was intermittent, detectible across all the sites that were monitored simultaneously, and followed no set pattern. The noise mostly registered between 45 and 60 decibels, which is comparable to the air traffic sounds in Seattle, Kuehne said. Occasionally, the sound level would hit 80 decibels or more, which is akin to the persistent noise when walking under Seattle’s former waterfront viaduct.

Original Paper: Kuehne LM, Olden JD. Military flights threaten the wilderness soundscapes of the Olympic Peninsula, Washington. BioOne Complete. 2020;94(2):188-202.

Source: UW News, BioOne Complete

Images: UW News, Lauren Kuehne