Interventional Audiology Services: Health Literacy | October 2016 Hearing Review

How to create (and review) informational materials that will benefit your patients

Health literacy—how people understand and act upon the information provided to them by their doctors and care providers— is an enormous problem within our healthcare system. Studies indicate that older adults with hearing problems are particularly at risk for low health literacy. A small investment of time spent in creating patient-friendly materials will provide return on investment, including greater efficiency in your practice, a more informed and empowered patient, a more trusting relationship, and happier, healthier patients. Here’s how to do it.

Defined as the degree to which an individual can understand, process, and act upon information and decisions related to their well-being, health literacy is integral to health outcomes. At present, a staggering 90 million Americans do not possess adequate health literacy, thereby jeopardizing decision making and quality of their healthcare.1 Older adults with sensory deficits, including hearing loss, are at high risk for low health literacy levels.2

Knowing how hearing loss affects the way information is processed, retained, and applied, this should raise an ethical alarm for audiologists and other hearing care professionals. The evidence is clear: low health literacy is a stronger predictor of health outcomes than age, income, or race, and low health literacy is statistically linked to poorer health and quality of life.3

As such, health literacy is at the center of national and global research initiatives, under the umbrella of Public Health, and is increasingly a priority for hearing healthcare professionals, including manufacturers of hearing technologies. Further, given the challenges associated with affordability and access to hearing healthcare strategies, it is incumbent that health literacy be a priority—no matter the intervention strategy.

A Responsibility: Adequate Precautions Against Low Health Literacy

To minimize risks for all stakeholders, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) contends that health literacy should be viewed as a universal precaution, much like vaccinations and hand washing. To ensure that our patients make safe and appropriate healthcare decisions, hearing care professionals have a responsibility to make sure that patients understand the subtleties of hearing loss and its wide-reaching implications.4 A practice which prioritizes health literacy empowers its patients and helps to ensure successful rehabilitation outcomes—all of which contribute to a better quality of life.

Of particular relevance to hearing care professionals during testing and counseling is the use of decision aids or handouts, such as instructional brochures or communication strategies which help to optimize the transmission integral to shared decision making. Using clear written and oral communication strategies can help patients feel more involved in their healthcare and may increase likelihood of adherence to treatment plans.4 Additionally, providing both written and verbal information can increase knowledge as compared to verbal information as the sole modality. Regardless of literacy levels, patients prefer easy-to-read written materials and use of pictures to supplement counseling. Benefits include improved comprehension, shorter reading time, and enhanced self-efficacy.5-7

Verifying whether clinical materials meet health literacy standards using the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM)7 should be as automatic as measuring pure-tone thresholds. Developed in collaboration with health education scholars, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and the National Institutes of Health, SAM is one of the few standardized methods for evaluating the content and design of healthcare materials. The SAM is in Public Domain and searchable by the keyword terms “SAM+health literacy.”

Caposecco et al8 utilized the SAM to assess the literacy level of various instructional brochures distributed by hearing aid manufacturers and found that the majority scored poorly on content, graphics, self-efficacy, and learning motivation and stimulation. Doak et al7 suggested key factors for the development of education and counseling materials, which can be readily applied by audiologists:

Set realistic objectives

- Limit the scope of information to what the majority of the population needs now.

- Focus on concrete behaviors and skills rather than abstract facts.

Present context before concept

- State the purpose of the information before presenting it.

Partition complex information

- Break information into easy-to-use chunks.

- Sequence information with key points first.

- Leave areas of white space on the page.

- Summarize important points.

Use plain language

- Write at 5th grade level or below.

- Use second-person pronouns.

- Avoid jargon. Use active voice and keep sentences short.

- Use 14-point or larger, high-contrast, simple (sans sarif) fonts (eg, Arial, Helvetica).

Use simple pictures to enhance the message

- Caption and label all graphics.

- Avoid complex charts and graphs.

Putting Theory into Practice: A Case Study

In our work with a multidisciplinary clinical research team comprised of audiologists and physicians, we are using the Pocketalker 2.0™ to help older people with untreated hearing loss communicate better with first responders. The population is at known risk for low health literacy, so written instructions on how to use the device during their visit must be simple to ensure valid outcomes.

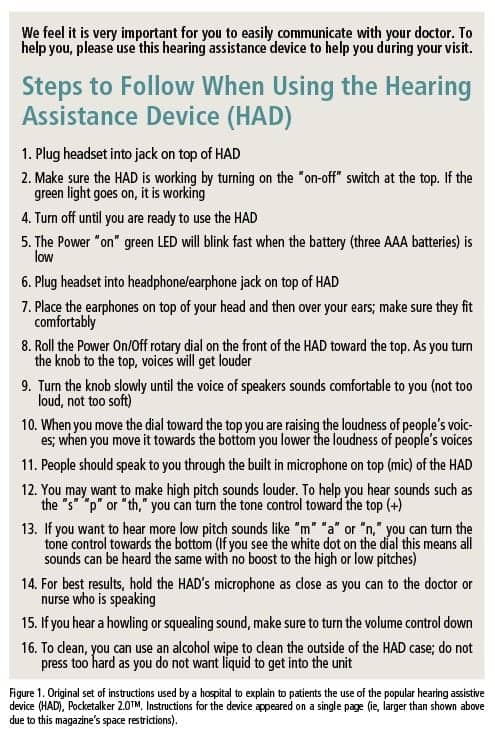

The original sheet of instructions created by the team of researchers is shown in Figure 1. The researchers felt that they designed this using “simple terms” to ensure intelligibility and ease of use.

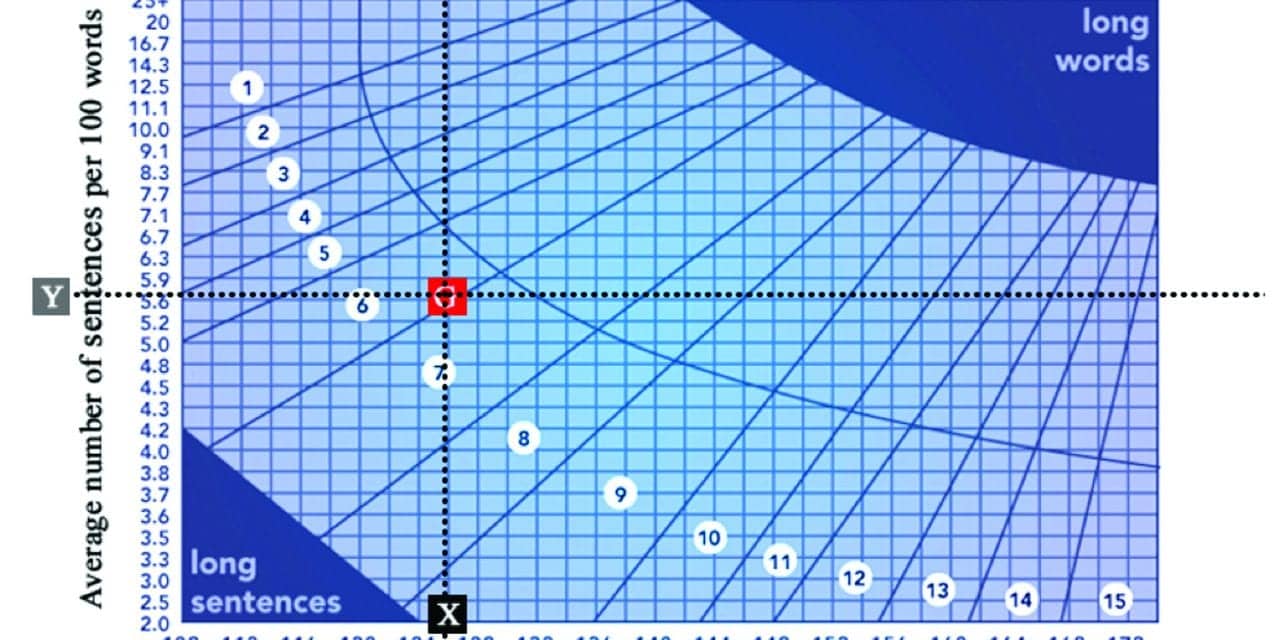

To assess the readability of the text and to ensure that it was at or below a 5th grade reading level, we pasted it into the readability algorithm at www.ReadabilityFormulas.com, with the result shown in Figure 2.

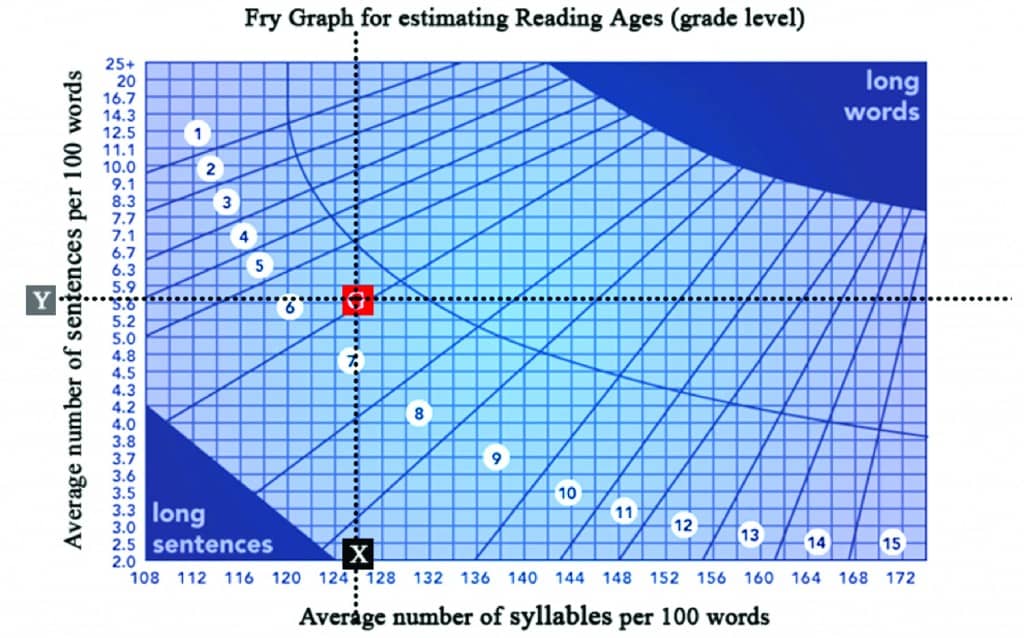

Figure 2. Frye Readability Graph for original set of instructions for Pocketalker 2.0™ (see Figure 1). Average number of syllables per 100 words = 126; average number of sentences per 100 words = 5.6.

The reading grade level of the material was 7th grade, with a recommendation that it be revised.

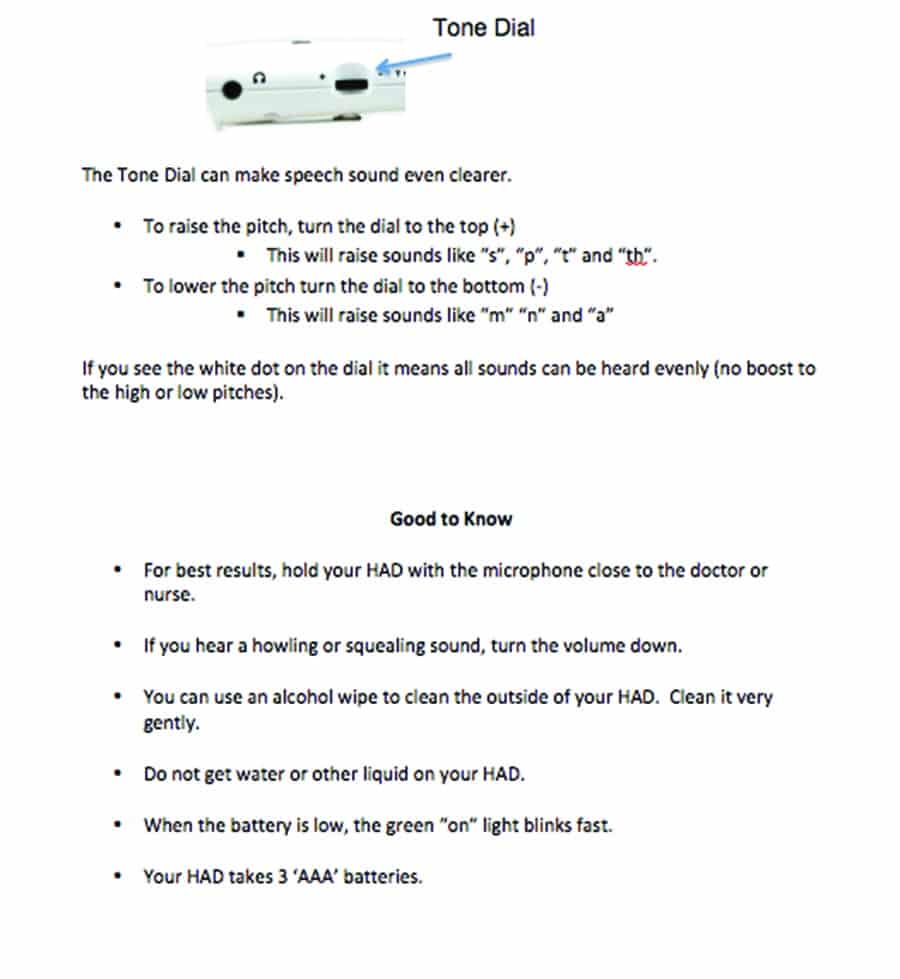

In light of this readability analysis, we further simplified the instructions for using Pocketalker 2.0™ with plain language as shown in Figures 3a and 3b.

Jargon was removed and long words were substituted with shorter, more common ones. Sentences were shortened and the active voice used.

Figures 3a, 3b. Revised instructions for the Pocketalker 2.0™ hearing assistive device (ie, revised from Figure 1). These instructions appeared on two pages in Arial 14-point type (reproduced smaller here due to space restrictions).

Importantly, there were also changes in the area of content, literacy demand, graphics, layout, and typography as detailed below:

For readability purposes the following changes were made:

- Font size was increased to 14-point with Arial, black on white background;

- Use of active voice;

- Information was broken into easy-to-use chunks and sequenced in a logical order, and

- White space was incorporated throughout document.

Written material was laid out with clearly labeled graphics depicting the controls and functions of the Pocketalker 2.0™. Original line drawings were replaced with color photographs of the device.

Simple summary points were included (eg, “For best results, hold your Pocketalker with the microphone close to the doctor or nurse”).

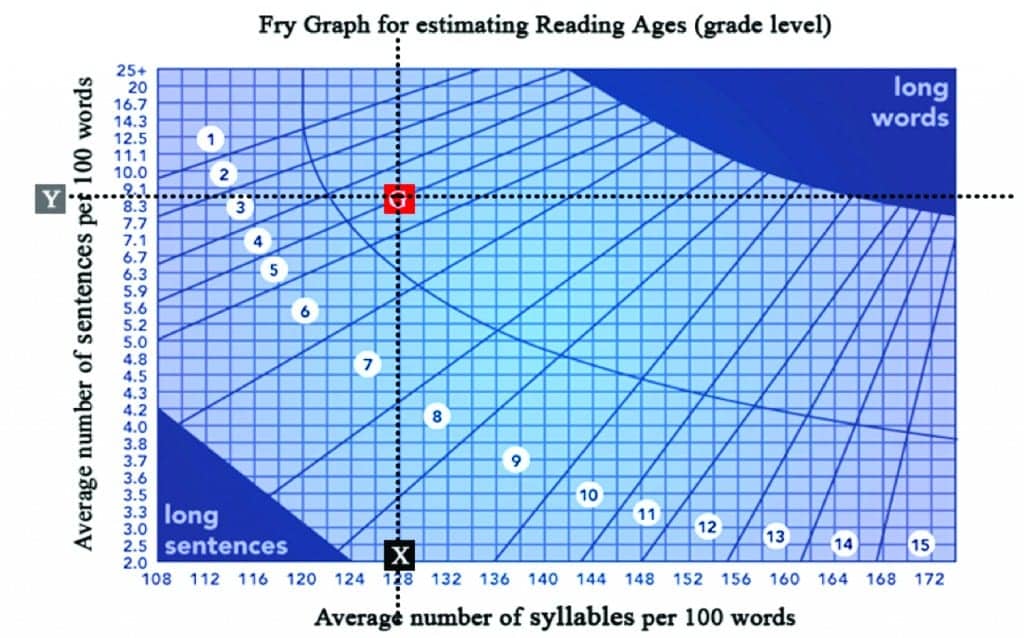

Figure 4 shows how the revised material meets a 4th Grade Reading Level. This compares favorably with the 7th grade level shown in Figure 2.

Figure 4. Frye Readability Graph for revised set of instructions for Pocketalker 2.0™ (see Figure 3). Average number of syllables per 100 words = 128; average number of sentences per 100 words = 8.3.

While shared decision-making and the use of materials at the appropriate literacy levels optimizes outcomes, hearing care professionals are generally reluctant to perform health literacy checks on their materials. Reasons range from a perceived lack of time to lack of awareness and lack of clarity about the benefits. We would argue that a small investment of time spent in creating patient-friendly materials will provide return on investment, including a more informed and empowered patient, a more trusting relationship, and happier, healthier patients. The bottom line is the cost benefits of creating patient-friendly materials are numerous, including increased revenue, better patient outcomes, and delivery of “gold-standard” patient-centered care.

Acknowledgement

This article is based in part on Dr Gilligan’s Capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the AuD degree, May 2016.

References

-

Kutner M, Greenburg, E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2006-483. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics;2006.

-

Safeer RS, Keenan, J. Health literacy: The gap between physicians and patients. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(3):463-468.

-

Berkman ND, Sheridan, SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2), 97-107.

-

DeWalt D, Callahan L, Hawk V, Broucksou K, Hink A, Rudd R, Brach C. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. [AHRQ Publication No. 10-0046-EF.] Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2010.

-

Davis TC, Bocchini JA Jr, Fredrickson D, Arnold C, Mayeaux EJ, Murphy PW, Jackson RH, Hanna N, Paterson M. Parent comprehension of polio vaccine information pamphlets. Pediatrics. 1996;97(6):804-810. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8657518

-

Sudore RL, Schillinger D. Interventions to improve care for patients with limited health literacy. J Clinical Outcomes Management. 2009:16(1):20-29. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20046798

-

Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. Am J Nursing. 1996;96(12):16-20.

-

Caposecco A, Hickson L, Meyer C. Hearing aid user guides: Suitability for older adults. Int J Audiol. 2014; 53[Supp 1]:S43-S51.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Dr Weinstein at: [email protected]

Original citation for this article: Gilligan J, Weinstein BE. Incorporating Health Literacy into Your Hearing Care Practice. Hearing Review. 2016;23(10):26.?

Other Articles in This Special Edition about Interventional Audiology Services:

Introduction: Interventional Audiology Services: Meeting the Demands of Today’s Consumer, by Brian Taylor, AuD, Guest Editor

What Hearing Care Professionals Need to Know About Today’s Healthcare Economics, By John Bakke, MD, MBA

Intervening in the Care of More Patients: Beyond Clinic-based Testing and Fitting, by Brian Taylor, AuD

Patient Engagement Through Interventional Counseling and Physician Outreach, by Robert Tysoe

Patient Complexity and Professional Time: Improving Efficiencies in the Service Model, by Dan Quall, MS, and Brian Taylor

Thinking Outside the Booth: Three Overlapping Categories of University Audiology Outreach, By Melanie Buhr-Lawler, AuD