|

| Vishakha W. Rawool, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology at West Virginia University, Morgantown, WVa. Jessica M. Kiehl, AuD, (not pictured) is a graduate of Bloomsburg University and is now an audiologist at Sonus Hearing Care Professionals, Camphill, Pa. |

Counseling helps patients overcome denial, but some patients regress post-counseling

The incidence of hearing loss increases with age. Hearing impairment ranks third among the most prevalent chronic health conditions in the elderly.1-3 The main avenue for treatment of sensorineural hearing loss is hearing aids. Randomized control trials have shown that veterans assigned to receive hearing aids experience significant improvements in social function, communication function, and depression after 4 months compared to a control group and the improvements are sustained 1 year after the hearing aid fitting.4,5 Based on a systematic review of literature, Chisolm et al6 concluded that hearing aids improve Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) by reducing psychological, social, and emotional effects of hearing loss.

Unfortunately, few adults seek treatment for hearing loss. For example, Popelka et al7 found that only about 20.7% of individuals with any hearing loss use hearing aids. This statistic has not changed much over the years. In 2005, about 31.5 million individuals in the United States reported hearing difficulty but only about 6.2 million (20%) individuals were active users of hearing aids.8

Effects of Untreated Hearing Loss

Untreated hearing loss has many adverse effects. Individuals with hearing loss can have emotional, social, physical, cognitive, and behavioral problems.4 Such individuals are more likely to be tensed, irritated, or frustrated not only during communication but also in other daily situations. They report feelings of inadequacy in everyday interactions, of being constraining to others, or being abnormal, prematurely old, diminished, or handicapped.9 Some individuals with hearing loss report experiences of being the object of hurtful jokes or of pity.

Because of the feelings of inadequacy and the fear of being ridiculed, older adults with untreated hearing loss may avoid social gatherings. Thus, not surprisingly, hearing loss is associated with reduced socialization and outdoor activities.10 It can also lead to physical fatigue. Many older adults get physically fatigued when they must ask for repetitions and must pay increased attention when around others who do not have a hearing loss.9

Hearing loss can also have an adverse effect on personal safety. Many individuals with untreated hearing loss are unable to hear a person walking or riding a bike behind them or a vehicle approaching behind them. While riding a bus, they may not hear the bus conductor announcing the next stop.11 Depending on the severity of the hearing loss, some older individuals may not hear someone entering their home or the telephone or doorbell ringing.

Effects of Untreated Hearing Loss on Significant Others

Hearing loss also affects the family and friends. Hetu et al9 found that an untreated hearing loss might cause relationship problems due to misunderstandings arising from not answering questions at all or responding inappropriately. Some significant others may often be required to cope with stressful communication situations by serving as mediators or interpreters and by speaking loudly or closer to the ears.11 Many individuals with untreated hearing loss need a period of quiet after difficult listening situations to recover from fatigue.12 This can cause the spouse or significant other to feel rejected or misunderstood. Individuals with untreated hearing loss may unconsciously raise their voices, which can be misinterpreted as anger or a harsh temperament by family members, acquaintances, or strangers.9

Any or all of these issues can lead to reduction in the frequency of interactions, intimate communications, and everyday companionship. The spouse or significant other deals with many situations other than communication problems in the relationship. They can feel deprived of opportunities to go out or feel isolated during social gatherings. Also, at times they feel that they must leave early; or even feel embarrassed by the hearing-impaired spouse. They may experience additional stress because of their inability to rely on the hearing-impaired person in potentially dangerous situations.9

Furthermore, if the hearing-impaired individual denies the hearing loss, it cannot be discussed openly in the family and thus the psychosocial costs for the spouse to adjust to the hearing loss are not acknowledged, leading to frustration and anger.13 Overall, spouse hearing loss can increase the likelihood of subsequent poorer physical, psychological, and social well-being in partners.14 Corbin et al15 reported that symptoms of hearing impairments such as irritability, inattention, and inappropriate responses are often misinterpreted as symptoms of dementia by caregivers.

Effects of Untreated Hearing Loss on Society

Because of the social isolation mentioned previously, individuals with untreated hearing loss may not contribute as much to society as other individuals. They may be less likely to volunteer at hospitals, libraries, or other similar places. They are also less likely to go out and spend money at theaters, movies, or restaurants.

The impact of untreated hearing loss has been quantified to be in excess of $100 billion annually. Assuming a 15% tax bracket, the cost to the society could exceed $18 billion due to unrealized taxes.16 Helping older adults to accept their hearing loss and purchase and seek aural rehabilitation including hearing or assistive listening aids can improve the quality of their lives and will be beneficial to society in general.

Possible Reasons for Untreated Hearing Loss

One of the possible reasons for untreated hearing loss is that the individual may be unaware of the loss. This may occur due to the fact that age-related hearing loss generally begins in the higher frequencies that have less impact on the ability to recognize speech in quiet surroundings. Furthermore, the loss progresses slowly with increasing age.

Another possible reason is denial of the existence of hearing loss. Denial is a natural response that allows individuals to minimize the natural impact of stress-provoking situations. It is easier to deny a hearing loss since it is invisible. People can be in denial without being aware of it. Studies suggest poor insight into the existence of hearing loss and denial of such loss by some individuals. Ownership of hearing loss is frequently denied and typically shifted to someone or something else (eg, the person speaking).17 Denial of hearing loss can result from the stigma associated with hearing loss or hearing aids, or the fear of negative social consequences.

Based on their data, Hetu et al18 suggested that the reluctance to acknowledge hearing loss may be an adaptive means to prevent being rejected, denied normality, mental integrity, and capability. Furthermore, patients are generally poor at judging the impact of hearing loss on their lives.19 People with progressive hearing loss may wait for 5 to 15 years before seeking professional help.20 There are inconsistencies or discrepancies between the perceived impact of hearing loss reported by the hard-of-hearing person and what is perceived by significant others.

Rationale and Purpose of Current Investigation

Although, in theory, socially active individuals can be expected to more likely use hearing aids due to the increased need of communication in social interactions and awareness of loss through demands on communication, it has been shown that about one-third of these individuals may be either unaware of their hearing loss or are in denial.21

There is a need to develop efficient and cost-effective approaches to help such individuals to accept the presence of hearing loss at an earlier stage of their hearing loss and at an earlier age. The purpose of this preliminary investigation was to evaluate the effect of a brief and individual-specific informational counseling session provided by a graduate student with limited clinical experience.

Methods. The current investigation is part of a larger study, which focused on the evaluation of the self-perception of auditory status among socially active non-hearing aid users.21

Participants. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. A total of eight men and 22 women in the age range of 65 to 89 years participated in the study. The mean age was 77.5 years. Participants were recruited through fliers and through friends and associates. All participants were middle-class Caucasian individuals. This allowed for control of any possible effects of cultural factors related to the perception of communication disorders.22 Only individuals above the age of 65 years were included since the prevalence of hearing loss is higher in this age group.

All participants were either members of different organizations (eg, Lions Clubs) or attended a number of social gatherings (eg, bridge club) on a regular basis (at least once a week) and thus were socially active. Such individuals can be expected to participate in voluntary or paid work.

Any participant who wore or ever owned a hearing aid was excluded from the study due to the focus of this study on unreported hearing loss and the effectiveness of counseling in acceptance of the hearing loss. Individuals who were previously seen in hearing clinics were excluded from the study. Participants diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease were excluded from the study to minimize the effect of cognitive limitations on the effectiveness of informational counseling.

Determination of perception of auditory sensitivity. To assess the participants’ perception of their auditory sensitivity, they were asked to respond in writing to the following question: Do you think you have a hearing loss? (Yes/No).

Audiometric test equipment, calibration, and test environment. A Maico MA 39 portable audiometer was used to measure the auditory sensitivity of participants. Exhaustive calibrations are performed on the audiometer annually. In addition, biologic calibrations were performed on a daily basis. The testing occurred in a quiet room, where thresholds of the tester in the room were within ±5 dB of those found in the sound-treated booth. As much as possible, the sites were chosen for participants’ convenience. The sites included residential homes, offices of different organizations, or rooms used for club activities.

Auditory threshold test procedure. The ascending method23 was used for threshold (softest audible sound) determination. The threshold was noted as the lowest level (dB HL), at which a minimum of two out of three responses occurred on ascending trials. Air conduction thresholds were obtained at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 kHz for both right and left ears. The frequency and ear order was randomized for each participant to minimize any order or fatigue effects.

Training for counseling to a graduate student. In order to provide client-specific counseling, perceptions of communication difficulties and perceptions about hearing aids of each participant were assessed by administering the Survey for Client Acceptance of Hearing Loss and Aids (SCAHLA).21,24 SCAHLA allows individuals to think more about their hearing loss by including questions such as “Do other people think that you have a hearing loss?,” “Do most people enjoy talking to you?,” or “How do people feel when you ask them to repeat?” The survey can also raise consciousness about hearing loss by making the individual think about issues such as the perception of mumbling. SCAHLA can elicit important information about the patient that can be used to provide individualized and efficient counseling.24 For example, depending on the responses given to the question, “Do you think hearing aids are expensive?,” cost-effectiveness of hearing aids can be explained to the patient.25

A graduate student (second author, currently an audiologist) with no experience with SCAHLA administration and very limited experience with counseling was trained prior to the initiation of data collection. She had previously completed a graduate course in aural rehabilitation and several other courses in audiology. A 3-hour training session on informational counseling was provided to the graduate student, since we were interested in evaluating the effects of counseling provided by individuals with limited training. The training included information about SCAHLA, its administration, and use. Two mock counseling sessions were held to demonstrate the use. At the end of the session, the graduate student demonstrated the informational counseling. The instructor (first author) provided feedback about the efficacy of the session and gave tips for making the counseling more effective.

Counseling procedures. Counseling was individualized for each participant depending on his/her auditory sensitivity, questions he/she had, and his/her responses to the SCAHLA survey. However, the following elements were common to all counseling sessions.

- There was a discussion and explanation of the person’s audiogram.

- All aspects of the audiogram, including the procedures used in detecting the softest audible sounds, were explained to the participants.

- The definition of normal auditory sensitivity (15 dB or below) was provided and compared to the hearing sensitivity of the participant.

- There was discussion about where the sounds of speech in average conversations are located on an audiogram, and how the participant’s hearing sensitivity can affect his/her speech perception. Visual aids with audiograms were used for this purpose.

- For those individuals who had a hearing loss at higher frequencies, the implications of the hearing loss (especially while listening in noisy situations) were discussed.

After these concepts were discussed, further information was provided based on the responses of the participants to the SCAHLA survey. For example, one question on the SCAHLA asks individuals if they hear ringing in their ears and, if yes, whether or not the ringing can be associated with a hearing loss. For those individuals who do not make the connection between tinnitus and hearing loss, additional information is provided related to this topic. The participants were probed throughout the counseling session to assure their understanding of the various concepts and to further expand on any misunderstood concepts.

Post-counseling inquiry about the self-perception of hearing loss. Immediately following the counseling session, participants were again asked to respond in writing to the following question: Do you think you have a hearing loss? (Yes/No). They were also reminded about the fact that they would receive the same question in the mail 1 month after the counseling session. The participants received the final administration of the question about their self-perception of hearing loss through the mail along with a preaddressed and stamped envelope.

Analyses. Due to the focus on acceptance of hearing loss, the average auditory thresholds obtained at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz were considered for determining the presence or absence of hearing loss. If the average threshold at the above frequencies was worse than 15 dBHL in the better ear, the individual was considered to have a hearing loss. We used a relatively strict criterion, with the goal of capturing even slight hearing loss at these frequencies, considering that older adults with even a marginal hearing loss show reduced emotional well-being and less satisfaction with independence.26 Also, older individuals often have worse hearing at higher and some at lower frequencies when there is only slight hearing loss at 0.5, 1, or 2 kHz (eg, see Table 2).

In addition, clinical experience suggests that the older the individual gets or longer the individual waits to obtain hearing aids, the harder time he/she has getting used to the amplification and maintaining and using the hearing aids. This may be due to a decrease in neuroplasticity with aging and/or lower cognitive flexibility. It can also be due to the fact that the auditory system may reorganize itself from age-related long-standing high-frequency sensory deprivation27 and then may have difficulty reorganizing following amplification. Only the better ear was considered since the better ear can contribute significantly to the perception of speech. Percent of individuals who accepted the hearing loss immediately following the counseling session and 1 month after the session was determined.

|

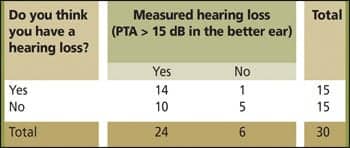

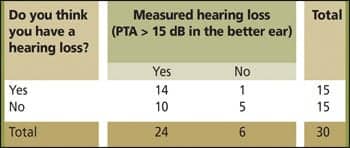

| TABLE 1. Comparison of self-reported versus measured hearing loss. |

Study Results

Audiometric and self-reported hearing loss in the study sample. Out of 30 individuals, 24 had hearing loss using the criterion of 15 dB or worse average thresholds at the frequencies of 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz. Thus, the incidence of hearing loss was 80%. Half (15 of the 30 participants) thought that they had hearing loss. Thus, the incidence of self-reported hearing loss was 50% (Table 1).

There was no significant correlation between self-perceived hearing loss at the initial contact and measured loss at the 0.05 level (contingency coefficient: 0.316, P = 0.068). The correlation was similarly non-significant following counseling. As can be seen in Table 1, one participant with no hearing loss based on her hearing at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz thought that she had hearing loss, but she did have severe hearing loss at higher frequencies and was counseled accordingly. It should be noted that, if the criteria of 15 dB HL or worse thresholds at any of the test frequencies were applied, all individuals in the current study would have been classified as having hearing loss.

Effect of counseling on acceptance of hearing loss. Of the 15 participants who did not believe they had hearing loss at the beginning of the study, 33% (5/15) were correct in their assumption. The 10 participants who had hearing loss but incorrectly thought their hearing was normal ranged in age from 74 to 88 years (Table 2). A total of five out of the remaining 10 participants accepted their hearing loss following counseling, although initially they denied having hearing loss.

Mixed Analyses of Variance revealed no significant differences in auditory thresholds between those who accepted their hearing loss immediately after counseling and those who did not. Visual examination of data suggests that the auditory thresholds are similar across the two groups (Table 2). One month after counseling, two of these five participants reverted back to denying their hearing loss (Table 2). Thus, although counseling was effective in helping 50% of the individuals in accepting their hearing loss in the short-term, the long-term success rate was 30% (3/10).

|

| Table 2. Effect of counseling on the acceptance of hearing loss on 10 individuals with hearing loss who initially believed that they did not have a hearing loss. Responses of participants to the question, “Do you think you have a hearing loss?” are displayed in columns 4, 5, and 6. |

Discussion

Acceptance of hearing loss immediately following informational counseling. The results show that audiogram- and SCAHLA-based counseling provided by a relatively inexperienced clinician is successful in helping 50% of the individuals to accept their hearing loss at least initially following counseling. Thus, this can be a relatively cost-effective strategy in outreaching a large number of individuals, with a somewhat limited outcome.

It should be noted that the graduate student (second author) who served as the counselor had only 30 days of clinical experience with counseling. One possibility is that having prior knowledge of the investigator being a graduate student with limited experience, the participants in the study may not have considered the investigator to be credible and thus may have been unwilling to change their opinions about their auditory sensitivity. Along the same lines, an experienced audiologist may have used the responses on the SCAHLA more efficiently, leading to more effective counseling. The counseling provided by the inexperienced clinician may have reached only those individuals who were somewhat unsure of their hearing status or suffered only from minimal denial.

Overall, current results suggest that among individuals who do not visit a clinic for hearing tests and who initially believe that they did not have a hearing loss, 50% (5/10) of the individuals will continue to deny their hearing loss soon after being informed that they have a hearing loss. A similar psychological minimization of undesirable results has been noted in other health settings. For example, experimental and observational evidence shows that individuals engage in psychological minimization (eg, lower ratings of the seriousness of high cholesterol) soon after being informed of undesirable test results following cholesterol screenings or blood pressure readings.28,29 Similarly, hypertensive patients tend to log blood pressure values lower than those displayed by their blood pressure monitor.30

Acceptance of hearing loss 1 month after counseling. One month after the counseling session, the acceptance rate in the current study dropped to 30%. Erler31 provided a brief counseling session to older adults with age-related hearing loss. Each of the 100 participants received approximately 15 minutes of brief counseling that included discussion of the results of an audiological evaluation; the effects of hearing loss on communication, interpersonal relationships, and emotional well-being; discussion of expectations of amplification; and identification of resources for hearing-related assistance. A 3-month follow-up survey revealed that 22 of these individuals subsequently obtained hearing instruments, suggesting clear acceptance of hearing loss among 22% of the individuals. It should be noted that we evaluated only acceptance of the presence of hearing loss, whereas Erler31 evaluated the acceptance of treatment. Some individuals may accept the presence of hearing loss, but may not seek treatment.

As stated previously, current results show that about 40% (2/5) of the individuals who initially accepted the hearing loss immediately following counseling reverted back to denying the hearing loss. In the current sample, reduced memory due to aging may be a contributing factor in accurately recalling the diagnosis of hearing loss. However, studies related to other types of health information also suggest inaccurate recall of presence of risk in about 40% of the individuals.32 More specifically, people tend to more accurately recall the absence rather than the presence of a risk factor. For example, 84% of individuals with normal cholesterol may correctly recall their risk status whereas only 59% of individuals with high cholesterol may correctly recall this condition.32 Furthermore, recall of self-relevant health information appears to be susceptible to self-enhancement bias regardless of age.33

Possible Reasons for Denial

Freud34 identified defense mechanisms as techniques used by the ego to protect it from the anxiety of threatening situations. In this context, denial is one of the defense mechanisms, and it is the refusal to acknowledge the reality of an unbearable condition or the feelings associated with it. Denial can also be seen as part of a grieving or emotional adjustment process consisting of five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.35

During the short period immediately after learning a health-related diagnosis or opinion, denial may be useful. It can allow the person temporarily to suppress awareness that something is wrong while his/her unconscious mind prepares to face the reality. Being in denial allows the person some time to deal with the challenges that lie ahead, such as purchasing and using hearing aids. A healthy way to cope with the situation is to face the facts and take appropriate rational actions after a short period of denial.

When denial persists beyond the short period and prevents the person from seeking appropriate help, it can be considered as maladaptive or harmful. In the case of hearing loss, the reluctance to acknowledge hearing difficulties can become a major obstacle to rehabilitation.36 The individual may become totally psychologically invested in believing that there is nothing wrong with his/her hearing and may show anger or rage toward anyone who questions his/her view of things. Usually, the denier unconsciously decides that awareness of certain feelings such as getting old, or being hearing-impaired, or objectifying the hearing impairment by using hearing aids is more threatening to his/her self-esteem than the act of denial. Thus, the person may use self-deception as a way of protection against an unacceptable reality or may modify the truth to be harmonious with his/her image of himself/herself37 as being young or having normal hearing.

In the current study, if this was the first time the study participants had heard the diagnosis of hearing loss, 1 month may have been insufficient time to go through the grieving process and come to terms with the diagnosis. On the other hand, participants in the current study are more likely to be aware of their hearing loss prior to the testing due to their social activities at least in noisy, group, and reverberant settings since many have significant hearing loss at higher frequencies (Table 2). Thus, these individuals may be in denial of hearing loss on a long-term basis. Adjustment to hearing loss requires a strong and flexible ego. A strong ego can sustain potentially devastating blows to self-esteem. A flexible ego may have the easiest time in accepting a possibly stigmatizing identity of hearing-impaired and handicapped person.38 Given the socially active nature of the current sample, ego-strength may not be an issue, but ego-flexibility may be a factor due to the age range of 74 to 88 years (Table 2).

Hetu et al13 suggested that individuals with hearing loss may be reluctant to acknowledge their hearing difficulties and may even deny having any hearing problems in order to protect their self-image. They studied two groups of hearing impaired workers and their spouses. The first group was composed of workers who had participated in a pilot rehabilitation program and had experienced the disclosure of their hearing difficulties by being a subject of a newspaper story on occupational deafness. Analyses of interviews conducted with these workers suggested that they were strongly stigmatized as being deaf, especially by coworkers. The second group consisted of workers who had had no previous contact with hearing professionals. The reluctance to acknowledge hearing difficulties among these workers was apparent through various forms of denial, minimization of the problem (eg, If I concentrate or pay attention, I can hear everything), and uneasiness in talking about the problem and in attempts to normalize themselves (eg, Everyone at my age and who has worked in a noisy situation can be expected to have a hearing loss). Hetu et al18 suggested that the reluctance to acknowledge hearing difficulties is part of an adaptive process that should be taken into account during the planning of interventions in future studies.

Suggestions for Future Studies

The current results suggest that the issue of hearing loss denial cannot be addressed permanently during one mostly informational counseling session. Further studies are necessary to see if inclusion of both informational and personal adjustment counseling over more than one session can improve the acceptance of hearing loss in older adults who have previously not sought any assistance related to hearing. The personal adjustment counseling should be designed to guide the patients in dealing with the emotional impact of the diagnosis of hearing loss. Issues such as denial of hearing loss resulting from stigmatization of hearing loss or hearing aids may need a more individual-specific approach.

Strategies need to be developed to help such individuals maintain a strong sense of self-worth and self-esteem while at the same time accepting the changes in roles, relationships, and self-image. In addition, it should be noted that, among older individuals, hearing loss might be viewed not only as a sign of aging but also the loom to the end of life.39 Thus, we need to emphasize the potential improvement in quality of life from acceptance of hearing loss and hearing aids.

Participants in the current study were older, socially active individuals who can be expected to be involved in voluntary or paid work activities and thus be productive members of society. Future studies with larger and more varied populations and more experienced counselors may be useful in further development and evaluation of efficient counseling strategies for improving long-term acceptance of hearing loss among older individuals or workers with hearing loss.

Conclusions

This study suggests that about one-third of socially active older adults who do not wear hearing aids and do not voluntarily visit hearing clinics are either unaware of their hearing loss or are in denial of the hearing loss. Informational counseling provided by a relatively inexperienced clinician can help about 50% of such individuals in accepting their hearing loss immediately after counseling. This suggests the need for the inclusion of personal-adjustment counseling to explore and address the emotional impact of the diagnosis of hearing loss. About 40% of the individuals who accept their hearing loss immediately following informational counseling can revert back to denial of hearing loss after 1 month, suggesting the need for additional follow-up counseling to reinforce initial acceptance.

References

- Adams P, Benson V. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1990. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 1991;10(181):1-212.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Careers Survey: Australian Users Guide. Canberra: Australia. Catalogue no 4431.0; 1993.

- Naramura H, Nakanishi N, Tatara K, Ishiyama M, Shiraishi H, Yamamoto A. Physical and mental correlates of hearing impairment in the elderly in Japan. Audiology. 1999;38(1):24-29.

- Mulrow CD, Aguilar C, Endicott JE, et al. Association between hearing impairment and the quality of life of elderly individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(1):45-50.

- Mulrow CD, Tuley MR, Aguilar C. Sustained benefits of hearing aids. J Speech Hear Res. 1992;35(6):1402-1405.

- Chisolm TH, Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, et al. A systematic review of health-related quality of life and hearing aids: final report of the American Academy of Audiology Task Force on the Health-Related Quality of Life Benefits of Amplification in Adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18(2):151-183.

- Popelka MM, Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, Klein BEK, Klein R. Low prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults with hearing loss: the epidemiology of hearing loss study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(9):1075-1078.

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrack VII: Hearing loss population tops 31 million. Hearing Review. 2005;12(7):16-27.

- Hetu R, Jones L, Getty L. The impact of acquired hearing impairment on intimate relationships: implications for rehabilitation. Audiology. 1993;32(6):363-381.

- Herbst KRG, Meredith R, Stephens SDG. Implications of hearing impairment for elderly people in London and in Wales. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1990;476:209-214.

- Hallberg LR, Barrenas ML. Living with a male with noise-induced hearing loss: experiences from the perspective of spouses. Br J Audiol. 1993;27(4):255-261.

- Hetu R, Lalonde M, Getty L. Psychosocial disadvantage associated with occupational hearing loss as experienced in the family. Audiology. 1987;26(3):141-152.

- Hetu R, Riverin L, Latande NM, Getty L, St-Cyr C. Qualitative analyses of the handicap associated with occupational hearing loss. Br J Audiol. 1988;22(4):251-264.

- Wallhagen MI, Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Impact of self-assessed hearing loss on a spouse: a longitudinal analyses of couples. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(3):S190-196.

- Corbin S, Reed M, Nobbs H, Eastwood K, Eastwood MR. Hearing assessment in homes for the aged. A comparison of audiometric and self-report methods. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1984;32(5):396-400.

- Kochkin S. Hearing loss and its impact on household income. Hearing Review. 2005;12(11):16-22. Also available at: http://www.betterhearing.org/pdfs/marketrak_income.pdf.

- Wolf KE, Hewitt EC. Hearing impairment in elderly minorities. Clin Geriatri 1999; 7(11):56-66.

- Hetu R, Riverin L, Getty L, Latande NM, St-Cyr C. The reluctance to acknowledge hearing difficulties among hearing impaired workers. Br J Audiol. 1990;24(4):265-276.

- Mulrow CD, Lichtenstein MJ. Screening for hearing impairment in the elderly: rationale and strategy. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6(3):249-258.

- Stephens SDG, Barcham LJ, Corcoran AL, Parsons AL. Evaluation of an auditory rehabilitation scheme. In: Taylor IG, Markides A, eds. Disorders of Auditory Function III. London: Academic Press; 1976.

- Rawool VW, Kiehl JM. Perception of hearing status, communication and hearing aids among socially active older individuals. J Otolaryngol. 2008;37(1):27-42.

- Bebout L, Arthur B. Cross-cultural attitudes toward speech disorders. J Speech Hear Res. 1992;35:45-52.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Committee on audiometric evaluation. Guidelines for manual pure-tone threshold audiometry. ASHA. 1978;20:297-301.

- Rawool VW. A survey to help older clients accept hearing loss and hearing aids. Hearing Review. 2000;7(5):34-41.

- Rawool VW. Overcoming obstacles in the purchase and use of hearing aids. Hearing Review. 2000;7(8):46-50.

- Scherer MJ, Frisina DR. Characteristics associated with marginal hearing loss and subjective well-being among a sample of older adults. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1998;35(4):420-426.

- Harrison RV, Nagasawa A, Smith DW, Atanton S, Mount RJ. Reorganization of auditory cortex after neonatal high frequency cochlear hearing loss. Hear Res. 1991;54(1):11-19.

- Croyle RT. Biased appraisal of high blood pressure. Prev Med. 1990;19:40-44.

- Croyle RT, Sun YC, Louie DH. Psychological minimization of cholesterol test results: moderators of appraisal in college students and community residents. Health Psychol. 1993;12:503-507.

- Johnson KA, Partsch DJ, Rippole LL, McVey DM. Reliability of self-reported blood pressure measurements. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2689-2693.

- Erler S. Brief counseling in audiologic practice [abstract]. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Annual Convention; December 1995; Orlando, Fla.

- Martin LM, Leff M, Calonge N, Garrett C, Nelson DE. Validation of self-reported chronic conditions and health services in a managed care population. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:215-218.

- Croyle RT, Loftus EF, Barger SD, Sun Y-C, Hart M, Gettig J. How well do people recall risk factor test results? Accuracy and bias among cholesterol screening participants. Health Psychol. 2006;25(3):425-432.

- Freud S. The Ego and the Id: Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Freud. Vol XIX. London: Hogarth Press; 1961.

- Kubler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York: Springer; 1969.

- Getty L, Hetu R. Development of a rehabilitation program for people affected with occupational hearing loss. 2. Results from group intervention with 48 workers and their spouse. Audiology. 1991;30:317-329.

- Hallberg LR, Barrenas ML. Coping with noise induced hearing loss: experiences from the perspective of middle-aged male victims. Br J Audiol. 1995;29(4):219-230.

- Rutman D. The impact and experience of adventitious deafness. Am Ann Deaf. 1989;134(5):305-311.

- Jones L, Kyle JG, Wood PL. Words Apart: Losing Your Hearing as an Adult. London: Tavistock; 1987.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR at [email protected] or Vishakha Rawool, PhD, at .

Citation for this article:

Rawool VW, Kiehl JM. Effectiveness of informational counseling on acceptance of hearing loss among older adults. Hearing Review. 2009;16(6):14-24.