|

| Jay B. McSpaden, PhD, BC-HIS, is an audiologist who retired from private practice and currently works as a hearing instrument specialist in Jefferson, Ore. Larry Brethower, ScD, BC-HIS, is a hearing instrument specialist who has been licensed in Missouri for 24 years, with 9 years of consulting/dispensing in Oregon. |

Symmetrical hearing loss is not quite as common as cursory inspection might suggest. Most professionals will say that symmetrical loss is more frequent than asymmetrical loss (although they may quibble about SPL/HL). Patients with asymmetric losses have been the subject of many studies in which the researchers have concluded that, because the binaural redundancy advantage tends to decrease as the average threshold differences of the two ears increase, these patients will not benefit as much from a binaural fitting. However, there are certainly other physical acoustic factors (eg, head shadow effect) and auditory processing factors (eg, squelch) that can contribute to audition and speech understanding in noise. Additionally, there are no events in which only one ear attends, and the hearing care field has spent almost its entire history fitting one ear at a time.

Almost any dispensing professional can provide a rundown of binaural benefits in their sleep. In a nutshell, proven binaural benefits include better listening in difficult environments and superior understanding of speech in competing noise. Bilateral amplification also helps patients localize sound sources, reducing the mental strain of listeners trying to follow conversations in challenging environments. In MarkeTrak surveys, Kochkin1 has shown that binaural users report significantly higher satisfaction scores on quality of life, subjective benefit, sound of their own voice, hearing soft sounds, sound localization, and value (performance versus price of the hearing aid).

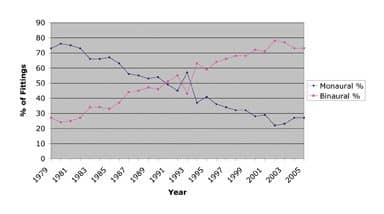

Earnest Zelnick, PhD, who passed away only a few months ago, wrote an influential article2 on binaural hearing in 1970 (at a time when binaural fittings were still thought by some to be “unethical”) and was among the first to call attention to binaural benefits. However, by the end of the 1970s, only about one quarter (27%) of hearing aid fittings were binaural; today, the percentages have almost flip-flopped with four in five (80%) of fittings being binaural (Figure 1).3

|

| FIGURE 1. The monaural versus binaural revolution: Fitting rates reached the 50%-50% point in 1992, and today binaural hearing aids constitute well over 70% of all hearing aid fittings in the United States.3 |

In spite of almost 40 years of recognizing the benefits of binaural fittings, we still do not concern ourselves with the concept of a “binaural target.” When you raise this subject to engineers and dispensing professionals, you generally get an embarrassed laugh and a shrug. There is no such thing as a dedicated binaural fitting algorithm or fitting method—even though logic dictates that some set of significant acoustic differences beyond summation should exist, necessitating fitting adjustments that differ according to whether one is specifying binaural or monaural hearing aids.

The following article grew out of an incident at a national meeting that the first author attended with colleagues. I mentioned needing to have my aids reprogrammed, as their recent repair had destroyed the benefits described above, or what I regard as the binaural fusion of the fitting. Each ear had been returned to a monaural “best fit.” As my hearing loss is both substantial and asymmetric, binaural fittings of monaurally set “best fit” hearing aids simply do not work.

Before the fitting session had ended, we had thrown out the targets; instead, live-voice in sound field was used to program the aids for the binaural fusion benefits that I view as crucial to achieving a satisfying fit. One of the major benefits of this type of fitting is “voice placement,” or a more natural localization effect: My voice and other people’s voices are perceived to be originating in their spatially appropriate places. Since I require my patients to “practice hearing” (acclimatization) by reading out loud for 30 minutes each day, I had to do the same. Trying this without the benefit of appropriately fitted binaural hearing aids is a drill that I don’t care to repeat.

Binaural Fusion: Doing the Best We Can?

When I was a child, my father taught me that it is not practice that makes perfect; it is perfect practice that makes perfect. Luck is mostly a function of hard work and preparation, and the more you practice, the luckier you get. Those lessons apply to hearing aids and aural rehabilitation as well as the game of professional golf in which he excelled. (Editor’s note: Jay McSpaden’s father, Harold “Jug” McSpaden, won 17 Professional Golf Association events.)

Back in 1985, Connie and Peter Mercola4 published a study about achieving binaural fusion in patients with asymmetric losses. Their methods involved identifying most comfortable loudness levels (MCLs) for each ear, leaving the best-ear MCL “on,” and turning the poorer-ear MCL “off.” Sitting in front of the patient, they would then ask the him or her about voice localization, as the volume in the poorer ear was increased until the sound of the dispenser’s voice was perceived by the patient to be at the front-center of their head. This was deemed the point at which binaural balance was achieved. At that point, the volume could be manipulated further from the binaurally balanced values (eg, 2-6 dB) to suit the patient’s preferences.

It should be acknowledged that, at about the same time, the amazing Cy Libby published his masterpiece Binaural Hearing and Amplification,5 and the equally amazing team of Silman, Gelfand, and Silverman6 published their classic work on auditory deprivation with monaural amplification. Also in those early days was hailed the advent of the now-maligned master hearing aid, through which an approximation of “summation” could be reached. We see many of these same successful dispensers today doing essentially the same things they always did, in the same way they always did them, with many not quite knowing why their methods work.

Therefore, these dispensers from the 1980s could not effectively convey their success to the generations that followed them. However, relative to binaural fusion, today’s dispensers have arrived at virtually the same conclusion through different tools and fitting methods: While there are no statistical targets in the “binaural fusion” mode, there is an operational one that has been tacitly agreed upon for years.

Binaural Fittings with Asymmetric Losses

One of the most commonly used methods that deals with binaural fitting is simply one of “getting close” using the better ear as a base, then lowering the gain by about 3 to 5 dB on the output in each ear until the patient is satisfied with the fitting. Similar to Mercola’s method,4 the aids can then be further adjusted for localization or voice placement.

Voice placement asks the patient to identify the location of his or her own voice, ranging from “back in my own throat,” “way out in front,” or “1 inch in front of my lower lip.” These three options can be chosen by the patient while he or she is speaking in a normal voice, at normal levels, and saying a word with a sibilant /s/ in it, such as /cheese/, /cheese/, /cheese/. This phoneme is difficult to hear for those with high-frequency hearing loss, or for those who have been using older aids that do not adequately amplify the higher frequencies. The goal of adjusting the aid is to get patients to perceive their own voices 1 inch in front of their lower lips and the sound of a speaker’s voice “binaurally fused” in the center of their head.

One possible neurological explanation for this approach is that there are fibers in a band through the corpus callosum connecting the two hemispheres of the brain. The temporal processing time required for response is on the order of fractions of milliseconds, and this is primarily responsible for the gestalt of a fused signal. Time differences exceeding those parameters create a reverberant acoustic shadow effect that can affect signal clarity.

Other Considerations

As always, make sure to obtain a complete medical clearance—this is especially important if the asymmetric loss resulted from a sudden loss (ie, the patient needs to see a physician urgently). Additionally, you may need to consider a CROS or BICROS aid if there is a >60 dB difference between the thresholds and no air/bone gap.

Direct stimulation of the poorer ear requires that the residual area be thoroughly mapped and delineated. This mapping of the complete residual auditory area permits programming for the fullest sound, and therefore, the best speech understanding. For a review, the reader is referred to the authors’ article in the February edition of HR.7

|

| Binaural hearing “Cochlear Implants and Hearing Instruments: Do They Mix?” By Marsha Simons-McCandless, MA, and Clough Shelton, MD, FACS. November 2000 HR. “Testing Digital and Analog Hearing Instruments: Processing Time Delays and Phase Measurements.” By George Frye. October 2001 HR. |

Binaural fusion/balance provides the patient with better sound localization, word recognition ability in competing noise environments, and better perceived sound quality. Even if it appears that the hearing aid in the better ear may be programmed easily with adequate gain to “hit a target,” gain should be reduced when necessary to accomplish binaural balance with the poorer ear. In most cases, it has been the authors’ experience that a balanced binaural fitting improves customer satisfaction.

Stay Tuned

The concept of binaural fitting strategies for asymmetric and symmetric losses may be entering a new era. Hearing aids are now being introduced that connect with and transmit data to each other in ways that have never been possible (for a review, see the articles in HR by Powers and Burton,8 Fabry9 (both linked in the references below), and the article by Lindley in this edition). This has the possibility for opening up entirely new avenues of research and processing strategies that could bring even greater promise for binaural fusion that benefits the consumer.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Jay B. McSpaden, PhD, at .

References

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrak V: Consumer satisfaction revisited. Hear J. 2000;53(1):38-55.

- Zelnick E. Comparison of speech perception utilizing monotonic and dichotic modes of listening. J Aud Res. 1970;10:87-97.

- Strom KE. Rapid product changes mark the new mature digital market. Hearing Review. 2006; 13(5):70-75.

- Mercola P, Wenke-Mercola C. A new test procedure for determining binaural candidacy. Hear J. 1985;19-26,31.

- Libby ER. Binaural Hearing and Amplification. Chicago: Zenetron; 1980.

- Silman S, Gelfand S, Silverman C. Late onset auditory deprivation: effect on monaural versus binaural hearing aids. J Acoust Soc Am. 1984; 76(5):1357-1362.

- McSpaden JB, Brethower L. Understanding transitions: between then and now. Hearing Review. 2007; 14(2):14-22.

- Powers TA, Burton P. Wireless synchronization in hearing aids: questions and answers. Hearing Review. 2005;12(1):28-30,89>.

- Fabry DA. In one ear and synchronized with the other: automatic hearing instruments under scrutiny. Hearing Review. 2006;13(12):36-38.