According to a new study from Brown University, an aging brain may be able to learn tasks just as easily as a young brain, but it utilizes a different area for learning. Researchers say that brain plasticity doesn’t necessarily decline with age, it may just shift with the whitening of hair to the brain’s white matter. The study, published online in the November 19, 2014 edition of Nature Communications, contradicts a previous belief held by brain scientists that as we age, our brains lose the neural flexibility (plasticity) required to learn new things.

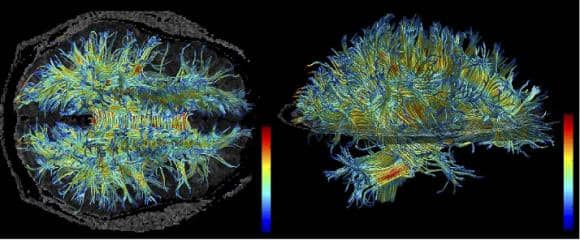

The Brown University researchers found that when many older subjects learned a new visual task, there was a significantly associated change in the white matter of the brain. White matter is the brain’s “wiring,” or axons, sheathed in a material called myelin that can make transmission of signals more efficient. Younger learners, meanwhile, showed plasticity in the cortex, where neuroscientists expected to see it.

“We think that the degree of plasticity in the cortex gets more and more limited with older people,” said Takeo Watanabe, PhD, the Fred M. Seed Professor at Brown University, and a co-author of the study. “However, they keep the ability to learn, visually at least, by changing white matter structure.”

The Differences in How Brains Learn

According to the report, the team’s study enrolled 18 volunteers aged 65 to 80 and 21 volunteers aged 19 to 32 to learn and perform an abstract visual perception task in the lab over the course of about a week. Participants viewed screens showing a background texture of lines oriented in a particular direction. Sometimes a small patch of the screen would briefly show lines pointing in one of two different directions against the background. Subjects had to push a button indicating they saw a patch with a particular orientation.

MRI image of brain showing the structure of myelin-sheathed wiring (white matter). The study showed that white matter changed in older subjects to allow for learning, while younger subjects learned via changes in gray matter.

The researchers say that individuals varied, but older subjects were just as likely on average as younger ones to make substantial progress in discriminating the small patch’s different texture. The research team reportedly wasn’t just interested in whether learning occurred. They also scanned the brains of the volunteers at the beginning and the end of the week using magnetic resonance imaging, which can indicate plasticity in the cortex. They also used diffusion tensor imaging, which can indicate changes in white matter.

The scans focused on the section of the brain responsible for visual learning, the early visual cortex (gray matter), and on the white matter beneath it. Moreover, the researchers strategically positioned the texture patch in the same part of the subject’s visual field. That was to ensure that a specific part of the visual cortex (and white matter beneath) that handles signals for that section of the visual field would be trained, while other sections would not.

Researchers analyzed the brain scan results and the learning performance results together, finding some important associations:

- For changes in the cortex, younger learners showed significantly more than older learners. For changes in white matter, older learners showed significantly more than younger learners;

- In volunteers of both age groups, brain changes occurred only in the sections corresponding with the specific part of the visual field where the patches occurred.

In looking more deeply at the association between white matter changes and learning performance in the older subjects, the researchers found that they separated into two clearly distinct groups: “good learners” and “poor learners.” In the group that learned very well (their accuracy in discriminating the patch increased by more than 20 percent), members showed a positive association between white matter changes and their improved learning. But among the “poor learner” group (which had a less than 20 percent improvement), the trend was that learning improvement decreased with greater white matter change.

The study doesn’t explain what accounted for why older subjects fell into one group or the other. The results also don’t definitively explain why white matter plasticity would enable good learners to learn well, although improved signal transmission efficiency is one hypothesis.

The study’s lead authors are Yuko Yotsumoto of the University of Tokyo and Li-Hung Chang of Brown University and National Yang Ming University in Taiwan. The corresponding author is Yuka Sasaki, associate professor (research) of cognitive, linguistic, and psychological sciences at Brown University. Other authors are Rui Ni of Wichita State University, and Russell Pierce and George Andersen of the University of California–Riverside. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Source: Brown University

Image credit: 3D Slicer, Wikimedia Commons