Tech Topic | August 2021 Hearing Review

By George Cire, AuD; Chris J. James, PhD; and Paula Greenham, MSc

Although the worldwide hearing loss population is about 1.6 billion people, we now have a hearing solution for the vast majority in the form of hearing aids and implantable solutions that include cochlear implants, middle ear implants, and bone anchored hearing devices. This article reviews these major treatment modalities, the general indications for implant use and referral, and presents a picture of current clinical practice as reflected in Cochlear Ltd’s Implant Recipient Observational Study (IROS).

An estimated 1.6 billion people globally had hearing loss in 2019, and of these, well over a quarter had hearing loss that was at least moderate in severity. With an aging population, this problem is only set to grow in both size and severity. Hearing loss is known to significantly reduce quality of life and is the third-leading cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) for all ages and the leading cause among the age 70+ population.1 Many of the negative effects of hearing loss can be ameliorated with the correct amplification using conventional hearing aids or implanted hearing devices.2

It is the hearing care professional’s responsibility to choose the best type of amplification device for an individual patient. Their choice is based on patient needs and the severity and exact nature of the hearing loss. Losses can be sensorineural only, conductive only, or a mixture of the two. Hearing aids perform well for those with mild-to-moderate sensorineural losses, but are less effective when the sensorineural loss is severe-to-profound. Hearing aids are also less efficient when there is a substantial conductive element, or air-bone gap. These are the situations where implanted hearing devices have a role to play.

Implanted Hearing Devices

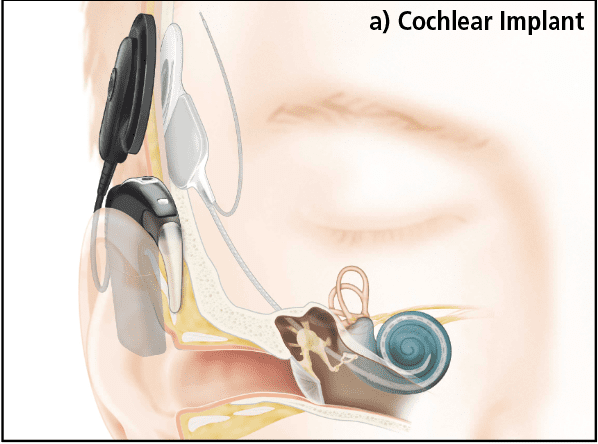

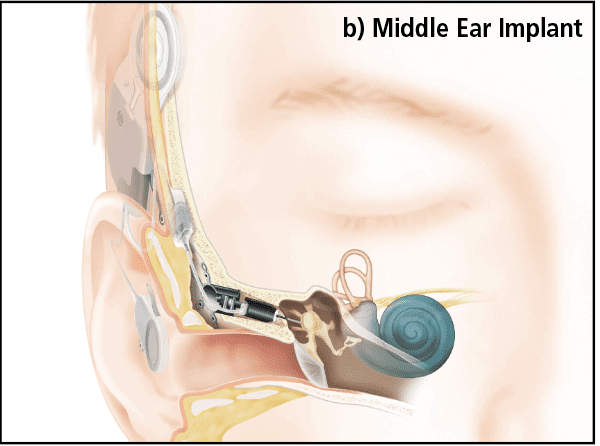

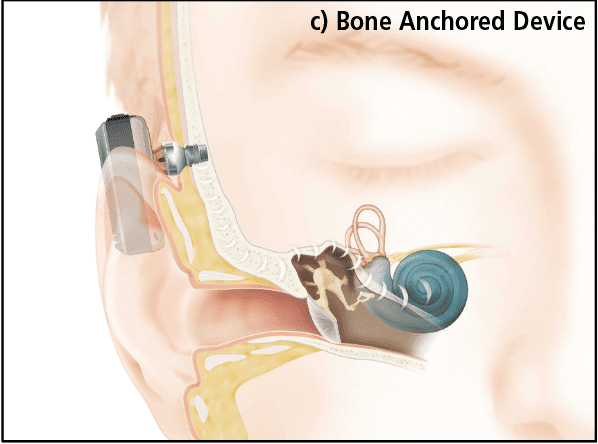

There are three main groups of implanted hearing device: cochlear implants, active middle ear implants, and bone anchored hearing devices. Each device targets a specific region of the ear and works in a slightly different way.

Cochlear Implants (CIs) bypass the outer and middle ear and directly stimulate the auditory nerve via an electrode array inserted into the cochlea (Figure 1a). In Nucleus® devices manufactured by Cochlear Ltd, there are 22 individual electrode contacts which deliver electrical pulses to the auditory neurons within the modiolus. An external speech processor is worn that looks much like a behind-the-ear hearing aid. Unlike a hearing aid, which simply amplifies the sound, the CI processor codes the input from the microphone into a series of electrical pulses which are sent across the skin via a radio wave to an implanted receiver, which in turn delivers the stimulus to the electrode contacts. The internal and external parts connect across the skin via a magnet allowing easy placement and removal.

Active Middle Ear Implants (AMEIs) are devices which act on the middle ear structures directly (for a historical review see Banakis et al, 20203). In the normal hearing pathway, the tympanic membrane converts sound energy to a physical vibration that is conducted to the cochlea by ossicles. AMEIs convert the microphone signals to vibrations in the middle ear (Figure 1b) by means of a linear actuator attached to a variety of points in the ossicular chain, depending on the AMEI type.

In the final implant category, Bone Anchored Hearing Devices bypass the middle ear and provide vibration directly to the mastoid bone via an osseointegrated titanium implant. In the Baha® devices (Figure 1c), manufactured by Cochlear Ltd, an externally worn processor provides the correct amount amplification or gain, adjusted according to the sensorineural hearing loss, much in the same way as the gain is adjusted in a conventional hearing aid. The processor either connects to the implant with an abutment through the skin, as in the Baha Connect device (shown), or across the skin via an implanted magnet as in the Baha Attract.4,5 An even more advanced bone conduction system is the Osia® System6 where a slim, high-powered actuator using piezoelectric vibration is implanted and connects to an external sound processor using a transcutaneous radio-frequency link much like a CI.

Indications for Devices Currently Available

Regulatory approved indications for each type of device vary across global regions. Some countries require patients to meet a maximum functional criterion (usually speech perception) with their current hearing aid and exclude certain patient groups, so country-specific approvals should always be consulted. Potential implant recipients are required to have compromised or limited benefit with hearing aids.

Cochlear implants. From an audiological perspective, CIs are suitable for patients with moderately severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss in the ear to be implanted. Most will have bilateral severe to profound hearing loss. For example, Zwolan et al7 propose a rule of thumb where patients with limited speech understanding and pure-tone average thresholds ≥60 dB HL in their better ear should be referred for CI candidacy evaluation.

However, in some regions, CIs are available for those with asymmetric hearing loss and single-sided deafness,8,9 and expanded indications include those with a severe high-frequency sloping hearing loss.10-12 Those patients who experience difficulties communicating with strangers or in a group, or who cannot use the telephone are most likely to benefit from a CI.13

Bone anchored hearing devices. Bone anchored hearing devices address those with conductive or mixed hearing losses. For mixed hearing losses, bone conduction solutions are effective because they bypass the conductive element and only need to address the sensorineural hearing loss.14 Device connection type (Attract, Connect, or Osia®) and sound processor selection depends on the unique physiology of the patient and the amount of sensorineural hearing loss and the subsequent amplification required. Suitable patients usually have audiological thresholds with an air-bone gap ≥30 dB HL and bone-conduction thresholds ≤ 65 dB HL across 500-3000Hz.

Bone-anchored hearing devices are also suitable for patients with single-sided deafness (SSD), acting as a contralateral routing device. The bone conduction system bypasses the deaf ear entirely and delivers the sound directly to the hearing ear’s cochlea across the skull.15

Active middle ear implants. Like bone-anchored hearing devices, AMEIs have traditionally been used in a fairly wide range of cases for individuals with mild to severe sensorineural hearing loss who cannot benefit from conventional hearing aids due to outer ear (eg, atresia) or middle ear pathology (eg, otosclerosis) and are not candidates for CIs. However, as explained below, the Cochlear AMEIs mentioned here are no longer available.

What Is Current Clinical Practice?

In 2013, Cochlear Ltd initiated and sponsored the Implant Recipient Observational Study (IROS), a voluntary registry to monitor patients receiving different kinds of Cochlear Ltd implantable hearing devices (ie, AMEI, Baha, and Nucleus CI). This voluntary database permitted participating centers to input general data such as age, along with audiometric data such as air- and bone-conduction thresholds, degree of hearing loss, etiology, use of hearing aids, duration of hearing loss and subjective quality of life questionnaires.16

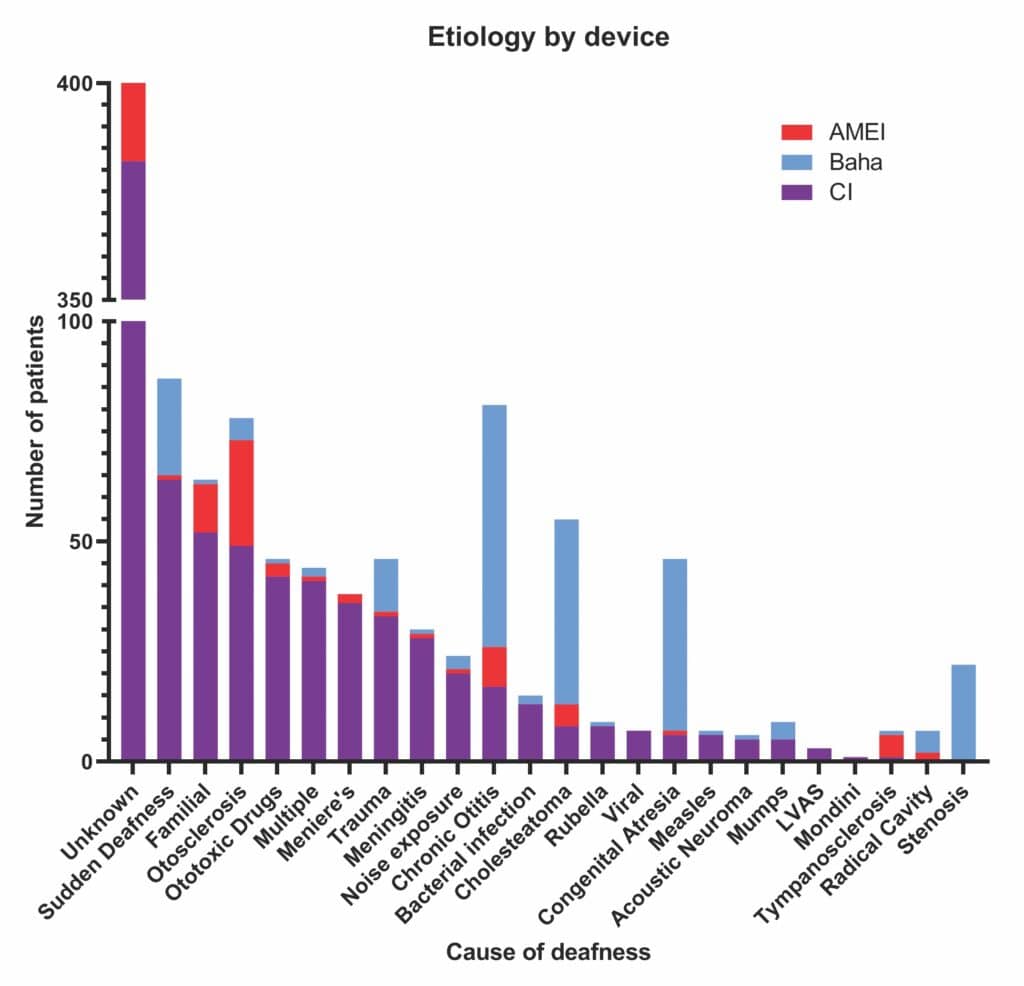

The different recorded etiological indications for the three devices are shown in Figure 2. In keeping with expectation, most of the Baha recipients had outer or middle ear conditions such as chronic otitis, cholesteatoma, or malformations such as stenosis or congenital atresia.17 Inner-ear diseases such as familial deafness, ototoxic drugs, meningitis, Meniere’s, viral infections, and noise exposure were near-exclusively treated with CIs. Most CI recipients had hearing loss of unknown cause, followed by those with sudden deafness.

Etiological indications for AMEI varied hugely, perhaps unsurprisingly given their wide criteria. Patents with otosclerosis had the greatest range of treatment options and many received the Codacs AMEI as expected (21/78), as this device was used mainly in the treatment of otosclerosis when stapedotomy and/or other options had not been successful.18 However, as seen in the IROS, CIs are also used to treat otosclerosis.19

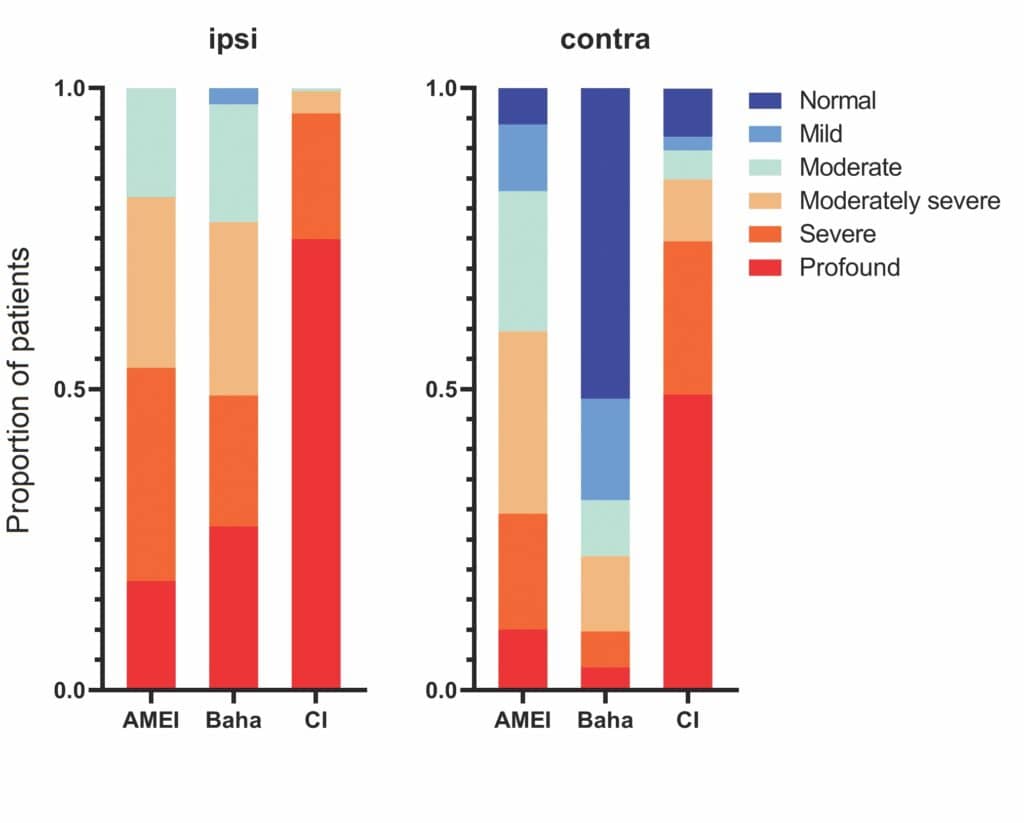

Figure 3 demonstrates the severity of hearing loss treated by each broad class of implantable hearing device in the IROS study. The proportion of recipients for each degree of hearing loss, based on air-conduction thresholds, for each device type is shown. Most of the patients in the IROS had a CI and therefore have profound or severe hearing loss, many exceeding measurable levels. The tendency towards less-severe hearing loss for AMEI and Baha can clearly be seen. Contralateral hearing follows a similar pattern with many Baha recipients having mild-to-normal hearing in the contralateral ear, reflecting the SSD indication for this device.

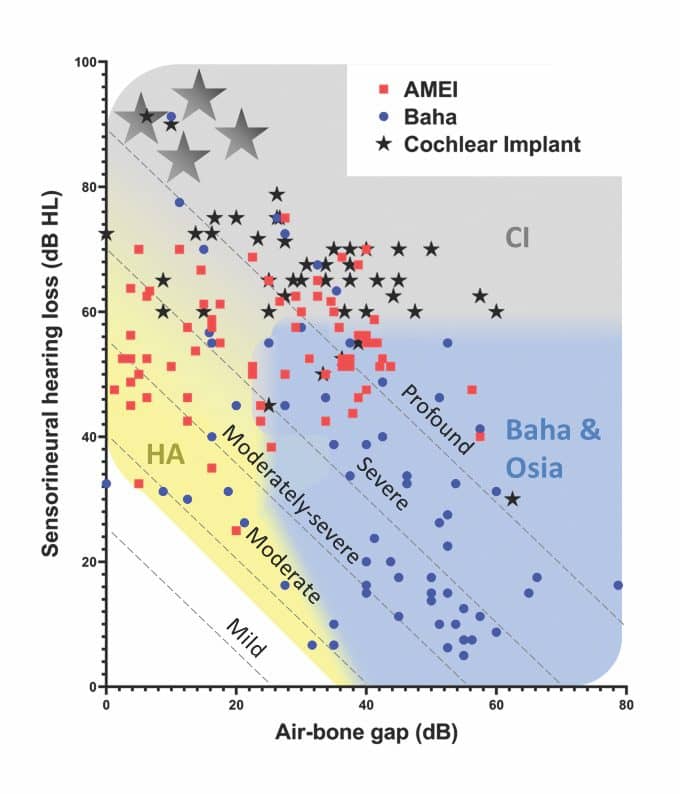

Pure-tone thresholds for the 180 patients who had measurable thresholds are shown in Figure 4 and broadly mirror the clinical recommendations. Patients implanted with AMEIs overlap with CI, HA, Baha, and Osia indications. This is unsurprising when you consider that AMEIs were generally used when a hearing aid was not suitable, and a CI was not yet indicated.21 With the introduction of more powerful bone-conduction devices, such as the Osia System and the Baha 6 Max, as well as expanded CI indications which take advantage of residual hearing in the implanted ear,11,22 the clinical need for the AMEI devices was significantly diminished. This is reflected in their discontinuation as Cochlear products.

Conclusions

We have explored how conventional hearing aids, cochlear implants, and bone-anchored hearing devices cover all audiological configurations of sensorineural, mixed, and conductive hearing loss.

Audiological indications for implanted devices fall broadly into the following categories:

Sensorineural hearing losses:

- Patients with moderately severe-to-profound hearing loss could consider a CI.

Conductive hearing losses:

- Patients with an air bone gap of 30 dB or more could consider a Baha or Osia device.

Mixed hearing losses:

- Patients with mild to moderately severe sensorineural component could consider a Baha or Osia.

- Patients with moderately severe to profound sensorineural component could consider a CI.

Implantable hearing devices should be discussed with hearing aid users who meet the criteria and could be expected to achieve better outcomes with an implantable device. Patients meeting these criteria should be referred for full candidacy assessment.

References

- Haile LM, Kamenov K, Briant PS, et al. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2021;397(10278):996-1009.

- Wilson BS, Tucci DL. Addressing the global burden of hearing loss. The Lancet. 2021;397(10278):945-947.

- Hartl RMB, Jenkins HA. Implantable hearing aids: Where are we in 2020? Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020;5(6):1184-1191.

- Gawecki W, Balcerowiak A, Kalinowicz E, Wrobel M. Evaluation of surgery and surgical results of Baha® Attract system implantations–Single centre experience of hundred twenty five cases. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;85(5):597-602.

- Briggs R, Van Hasselt A, Luntz M, et al. Clinical performance of a new magnetic bone conduction hearing implant system: Results from a prospective, multicenter, clinical investigation. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(5):834-841.

- Goldstein MR, Bourn S, Jacob A. Early Osia® 2 bone conduction hearing implant experience: Nationwide controlled-market release data and single-center outcomes. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42(1):102818.

- Zwolan TA, Schvartz-Leyzac KC, Pleasant T. Development of a 60/60 guideline for referring adults for a traditional cochlear implant candidacy evaluation. Otol Neurotol. 2020;41(7):895-900.

- Benchetrit L, Ronner EA, Anne S, Cohen MS. Cochlear implantation in children with single-sided deafness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(1):58-69.

- Marx M, Mosnier I, Venail F, et al. Cochlear implantation and other treatments in single-sided deafness and asymmetric hearing loss: Results of a national multicenter study including a randomized controlled trial. Audiol Neurootol. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1159/000514085.

- Huinck WJ, Mylanus EAM, Snik AFM. Expanding unilateral cochlear implantation criteria for adults with bilateral acquired severe sensorineural hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:1313- 1320.

- Buchman CA, Gifford RH, Haynes DS, et al. Unilateral cochlear implants for severe, profound, or moderate sloping to profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss: A systematic review and consensus statements. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(10):942-953.

- Varadarajan VV, Sydlowski SA, Li MM, Anne S, Adunka OF. Evolving criteria for adult and pediatric cochlear implantation. ENT Jour. 2020;100(1):31- 37.

- Müller L, Graham P, Kaur J, Wyss J, Greenham P, James CJ. Factors contributing to clinically important health utility gains in cochlear implant recipients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021. DOI: 10.1007/ s00405-020-06589-1.

- Colquitt JL, Loveman E, Baguley DM, et al. Bone-anchored hearing aids for people with bilateral hearing impairment: A systematic review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36(5):419-441.

- Kim G, Ju HM, Lee SH, Kim H-S, Kwon JA, Seo YJ. Efficacy of bone-anchored hearing aids in single-aided deafness: A systematic review. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38(4):473-483.

- Lenarz T, Muller L, Czerniejewska-Wolska H, et al. Patient-related benefits for adults with cochlear implantation: A multicultural longitudinal observational study. Audiol Neurootol. 2017;22:61-73.

- Dimitriadis PA, Farr MR, Allam A, Ray J. Three year experience with the cochlear BAHA attract implant: A systematic review of the literature. BMC ENT Disorders. 2016;16:12:1-8.

- Lenarz T, Zwartenkot JW, Stieger C, et al. Multicenter study with a direct acoustic cochlear implant. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(7):1215-1225.

- Calmels M-N, Viana C, Wanna G, et al. Very far-advanced otosclerosis: Stapedotomy or cochlear implantation. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 2007;127(6):574-578.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) website. Degree of hearing loss. www.asha.org/public/hearing/Degree-of-Hearing-Loss.

- Mlynski R, Plontke SK. Implantierbare hörgeräte: Das ergebnis hängt am detail. HNO. 2021;69:445- 446.

- Pillsbury HC III, Dillon MT, Buchman CA, et al. Multicenter US clinical trial with an electric-acoustic stimulation (EAS) system in adults: Final outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39(3):299- 305.

Correspondence to Dr Cire at: [email protected].

Citation for this article: Cire G, James CJ, Greenham P. When is an implantable hearing solution appropriate? Hearing Review. 2021;28(8):18-20.