Giving and receiving: Providing hearing care in Ulan Ude Buryatia, Russia

In the spring of 2004, I was approached to assist with information for a team of individuals who expressed an interest in providing hearing health care to a population of people in Ulan Ude Buryatia, which is located in Siberia. The team had learned that a significant number of people in Ulan Ude experienced hearing impairment, probably due to a high use of streptomycin in the past. They had also learned that little help had been available to assist these individuals.

I met with Don and Tricia Jones and Jeanne Kelley to brainstorm options, sources of assistance, and methods to begin to plan an effort to provide assistance to this group of people with hearing health needs in Siberia. An audiologist from our community, Kate Meade, also joined the team. We laid out plans to reach out to suppliers of hearing instruments, and we considered the many pros and cons of trying to provide help—especially those products and services that would yield continued benefit beyond one visit. This included the necessity for hearing aid orientation and training, as well as instruction for family members of those persons receiving hearing instruments.

Team members took the ideas and suggestions and were able to secure funding, supplies, and assistance to carry out what we believe was an extremely successful trip that provided rewards for many.

Reports written by members of the team of travelers to Siberia in August 2005 follow.

Hearing Health Care in Ulan Ude

By Don E. Jones

Several years ago, we were introduced to a group of workers involved in Community Development Projects in some of the remote areas of the world. The projects were conducted under an organization called Solbon International, and our new friends were currently working in Ulan Ude Buryatia, Russia. Ulan Ude is located in central Siberia just north of Mongolia and near Lake Baikal, the largest fresh water lake in the world.

Our friendship grew, leading to an invitation to visit the team in Ulan Ude. A team of three left Albany, NY, in May 2002. The purpose of this trip was to see the projects conducted in Ulan Ude and assess if there were areas that we might become involved.

In fact, the trip led us to make three more trips to Siberia. One sought to explore health care in villages outside major cities, and a second involved medical service provided in Ulan Ude. During the latter trip, we delivered medical supplies to various clinics and hospitals, purchased medicine for children at a TB hospital, and delivered two prosthetic legs made in Albany from specifications and photos delivered over the Internet.

During these two trips, we discovered that there was a large hearing-impaired population in Ulan Ude, and over the months, we developed a plan to conduct hearing clinics and to provide hearing aids purchased in the US.

On August 25, 2005, a team of four left Albany for Ulan Ude with what we had determined to be the appropriate requirements for the hearing clinics. In addition to myself, our team included Tricia Jones (my wife), audiologist Kate Meade, and Jeanne Kelley, who has a hearing impairment and has used hearing aids for many years. Our travel time covered 36 hours, and crossed 12 time zones to travel to central Siberia.

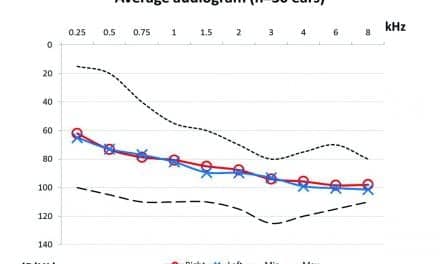

Local workers had pre-screened individuals whom they thought would most benefit from hearing testing and the hearing instrument equipment. This step enabled us to examine 65 individuals over the next four and a half days. Out of that population, we were unsuccessful in providing assistance to only three clients.

Some of the hearing instruments we brought were secured from ComCare International, and these consisted of 40 solar powered hearing aids. These hearing aids are able to maintain their power by being exposed to sunlight for only one hour per week. We also brought additional hearing aids provided by various vendors. All of the units were placed with persons with hearing impairment after completing an examination with an audiometer which we had secured on loan for the trip. All services and hearing aids were provided at no cost to the clients.

While the days were long, the hearing clinics proceeded without difficulty. Clients generally arrived long before their appointments. At the beginning of the trip, we did not fully realize how important our hearing-impaired team member would be valued. However, to our knowledge, Jeanne was the first hearing-impaired person ever to go to Ulan Ude with the expressed purpose of working with people in the deaf community. She spent at least an hour with each client after they had been fitted with their new hearing aids to train them in the use of the units and adjustment to sounds that were all new to them. She supplemented her sessions with written materials prepared in English and Russian distributed to each of the hearing aid recipients, as well as their family members.

The week had many emotional periods where we witnessed individuals hearing sound for the first time. Tears came to clients and the team alike as facial expressions changed and mothers heard their children speak—some for the first time. Children, after letting us test them, reacted to music and sounds. And then, on the second weekend, we met with many of the clients as they went to church and heard music and the lesson for the day—again, in many cases, for the first time.

We expect that about 19 of the 61 people receiving hearing aids would now be able to join the hearing community in Ulan Ude. We also observed the need for teaching individuals who were hearing the sounds of words that before they could only read.

And then, there was the larger deaf population whom we did not see, but many of whom could be helped through hearing clinics. The head of the deaf community and the city’s chief audiologist visited our clinic and asked us if we would come back and do a city-wide project. Just the thought of providing that kind of help and governmental access to people in the deaf community in Ulan Ude fills our hearts with hope and dreams.

We are currently working on the request for community-wide clinics and exploring the necessary funding and approvals that would make a second hearing clinic successful.

An Audiologist’s Perspective: Practical Considerations

By Kate Meade, MA

First, it should be mentioned that there are probably 1000 excuses for someone not to take part in these types of trips; for me, the main ones were five kids at home, lack of vacation time, and the monetary commitment required. But all those things were overcome, one by one. The first miracle was that donations more than covered the financial cost of the trip. In particular, donations of time from co-workers left me with an extra 37.5 hours of vacation, and there were many people from my church who helped to take care of my family. I felt that I could not ignore a need so specific to my professional skills—so I said yes.

Preparation for the trip included deciding what testing to do, securing hearing aids, determining the best choice for earmolds, preparing forms to document case history information and results, and preparing counseling information. Much of this work was completed by Jeanne Kelley. We had several meetings involving logistics, and it was made clear to me that I was the one with the academic training and knowledge about hearing and hearing loss and would, therefore, be making many of the practical decisions related to the testing and fitting of hearing aids.

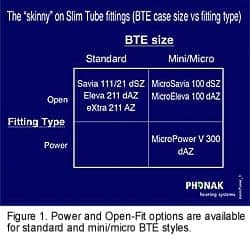

We had a budget of $5,000 provided by donations to cover our expenses. Much of this budget was consumed by the purchase of 40 solar-powered hearing aids from ComCare International. Those instruments were chosen because there were reports of difficulty obtaining hearing aid batteries in Ulan Ude. I was able to secure additional donations of eight new Classica hearing aids from Phonak Inc, two new Multifocus Compact hearing aids from Oticon, and 11 donated hearing aids that had been reconditioned and were in exceptional “like-new” condition (including one bone conduction aid). Donations of size 675 and 13 batteries to cover 1 year for each BTE hearing aid were also secured.

Having researched options for earmolds, it was decided that the best choice appeared to be an instant earmold material designed for this application by Westone Laboratories. They have designed a metal snap ring and tools which provide a unique method for making a custom mold for each person utilizing the ComCare solar-powered body unit. The material for the first 40 earmolds, including the snap rings and tools necessary to make the earmolds, was supplied free of charge by Westone. We purchased material for an additional 40 earmolds and tubing for the BTE hearing aids. At this point, I was amazed at how giving others are when a good cause is involved.

We did a dry-run fitting on Jeanne to be sure that the procedure for preparing the earmolds would work satisfactorily. She wore the ComCare solar-powered body hearing aid for nearly a week prior to departure without any earmold problems. Her observations about how the aid worked and the power of the unit helped with fine-tuning the units in the field to achieve maximum audibility without tolerance problems.

Prior to departure, I did perform electroacoustic testing of the hearing aids at all possible settings and simulated real-ear measures to check my choice of settings for several different hearing losses. In this way, I could be reasonably sure that I would set the hearing aids (as best as possible) in the field without verification beyond verbal feedback from the patient. While I would have liked to have had real-ear measures and tympanometry in the field, it was not possible to bring this additional equipment on the trip, as we had weight and baggage limitations.

We brought a Maico MA40 audiometer, an otoscope, tools for making the earmolds, as well as adjusting and listening to the hearing aids in the field. We attached a description of the audiometer’s purpose—written in Russian—to ease transfer through customs. I carried on as many of the tools needed for making the instant earmolds as I could, including my otoscope. My otoscope caused further inspection of my carry-on bag in the Moscow airport upon check-in for departure in both directions. The tools to make the sound-bore, a small screwdriver, and the custom tool for adjusting the body aids had to be transported in our checked luggage. Most of the hearing aids were checked, as well, to avoid unnecessary delays in customs. Unfortunately, the bag containing this equipment was lost, and there was a period when we thought that the clinic would be hobbled by this mishap. However, it arrived just in time for our Monday clinic.

Once we had arrived in Siberia, our clinic ran smoothly, thanks to much careful preparation. Once that last bag arrived, we were able to provide full services. I did not miss tympanometry as much as I thought I would. While we all know how a perfect match to real-ear targets does not guarantee consumer satisfaction with the hearing aid, I did miss that added level of verification during the fitting.

I was surprised at how long the process took with each patient. Testing, making the instant earmold, drilling the sound bore, modifying and finishing the mold for patient use, setting the hearing aid, and spending time verifying the settings of the hearing aid, as well as counseling the patient on use of the hearing aid, took over one hour per patient. There was no way to complete this process without help from all of my team members. After I completed all of the audiograms, made the molds, and set the hearing aids, I passed the molds onto Tricia Jones who worked on finishing the molds and drilling the sound bores. Then I would set the hearing aid parameters, and the patient moved to Jeanne who completed the hearing aid orientation and counseling.

The people were so thankful for our time and services. Translation from English to Russian and Russian to Russian Sign Language was tense at times. We cannot be sure that everything came through translation clearly.

The days were very long (12 hours). We tested 61 people and fit 58 hearing aids over four and a half days. There were three people who could not be fit due to the degree of hearing loss. There were two referred for wax removal, and both returned the next day (free of wax), telling us that they waited for hours to see a physician to get the wax removed.

We completed one television interview, met a local audiologist (to whom we gave the bone-conduction hearing aid for one of her young patients), trained a local young man to service and trouble-shoot the hearing aids, and enjoyed many Russian meals. In addition, we were able to do a little sightseeing on the Saturday before our departure.

This experience was a time of personal reflection and spiritual growth, a time of quiet reflection far away from the daily pressures, and a time of service to those in need. As I left, I wondered if I had left behind as much as I had gained.

Counseling and Caring

By Jeanne Kelley

Although I used to think mission trips were for people to travel somewhere to help change what is there, I have since realized that such trips are also to change the “go-er,” as well. My journey to Siberia really was an adventure that began when Tricia and Don Jones were inspired to try to help the people in the “deaf church” in Ulan Ude. They wanted to do something to help these people, and they worked hard to make it happen.

I was invited to participate on the team as an expert hearing aid user. I am not an expert at many things, but I have worn a hearing aid for the past 25 years, and I think that helps to qualify me as an expert. I have come to realize that, since the beginning of my hearing loss, I have been in training. Each stage of the hearing remediation process can be seen as a learning experience that enables us to help others. Becoming part of a local self-help group some 23 years ago was the most valuable step in my process. Our group, called Hearing Endeavor for the Albany Region (HEAR), is a chapter of Self Help for Hard of Hearing People (SHHH, recently renamed the American Association for the Hard of Hearing). HEAR helped me connect with others with hearing loss and receive the support needed to make it through those hard years of adjustment. The HEAR meetings, plus the SHHH conferences and conventions, taught many topics that truly could not be learned elsewhere. These laid a foundation for me to build a new life; a full life with a hearing impairment.

My job on the Ulan Ude team was to help the people receiving the hearing aids to learn how to use them; to understand what to expect; to talk to them about the emotional and psychological experiences related hearing loss; to help them work on improving communication; to encourage them, and to answer their questions based on my own experiences. I had actually learned much of this (and done all of this) in our support-group meetings.

I was given the distinction of being the first deaf/hard of hearing person to ever come to specifically visit with them. In some ways, they made me thankful to have a hearing loss, since it allowed me to be able to relate to these people and share things in ways I never would have been able to without a hearing loss. The experience enabled me to turn my disability into an ability.

Almost as important as the hearing aids was the encouragement we brought to these wonderful people. We showed them we cared. One of the most difficult experiences we had during our trip to Ulan Ude was to communicate. There were very few people who spoke English, and the ones who did were not fluent. Then there was the fact that most used sign language different from American sign language. After we spoke to our interpreter in English, they had to translate into Russian, and then to another interpreter who translated into sign. One interpreter spoke limited English and knew sign, which was wonderfully helpful.

For hearing aid orientation and counseling, I assembled segments from a book by audiologists Donna S. Wayner and Judy Abrahamson.1 After help from a Russian translator, each sheet was set up with two columns, with English on one side and Russian on the other. This allowed me to point to areas that we were discussing in Russian while I knew exactly what they were reading. Some of the topics covered suggestions for improving communication by being assertive, how to better communicate with a hard-of-hearing person, the impact of hearing impairment on emotions, and communication strategies. Each person and participating family members took one set of information home for future reference.

There were times which were frustrating for me because I believe the accompanying hearing people needed also to have some teaching about what should be expected from those receiving hearing aids. I was afraid too much was expected, which would inevitably lead to frustration. Those receiving the hearing aids also had high expectations, and I felt it important to reinforce realistic expectations. When I had an opportunity to address members of the whole community, including those with and without hearing aids, I suggested ways that those without hearing aids could help. In addition, I encouraged those with hearing loss to tell others of their disability and teach others how they can enhance communication.

As part of the experience, I wore the solar-powered hearing aid for five days. I did not feel right about wearing a much better hearing aid when most of those needing aids would be receiving the solar-powered instrument. The experience was different after being used to wearing a programmable aid. Often, because of the language barrier, the sign language barrier, and the difficulty in hearing, I felt very isolated. I had to work very hard at communicating, but do believe this was well worth it. I felt as if I may not have been received as well had I worn my own aid at the clinic.

I was surprised to find that the things I thought would be hard were not, but other things I had not considered were very demanding. Never did I expect that being so far from home would be so difficult. The language barrier made things extremely hard. Since my job was training, I felt challenged a good deal of the time. My interpreter was a wonderful person, and although I truly came to love her, her English was limited.

On our last day, I was able to address the whole church congregation. I spoke with the audience (both hearing aid users and non-users) about their expectations. People often tend to think hearing aids end the problem of hearing loss, so I explained that hearing aids are just the beginning and just an “aid.” They are not like eyeglasses; hearing does not become “20-20.” I tried to help them realize that people with hearing loss need assistance and offered some specific ways to do so (eg, facing the person they are speaking to, speaking slowly and clearly, giving feedback, and telling people what you need). I encouraged them not to be ashamed of their hearing loss, but to use it to help others. It was recommended that they talk about their hearing problems with each other—basically, the wonderful things I learned from my hearing loss support group that have helped me to help myself.

I have realized now that, without self-help, I never could have gone on this trip or been equipped to help anyone else without having first learned how to help myself. The trip itself, and talking about it afterwards, has helped my confidence to grow in new ways. It was an extraordinary experience.

| Donna S. Wayner, PhD, is president of Hear Again Inc, and former director of the Hearing Center at Albany Medical Center Hospital, Albany, NY; Don E. Jones and Jeanne Kelley live near Albany; and Kate Meade, MA, is senior audiologist at Sunnyview Hospital and Rehabilitation Center, Schenectady, NY. |

Reference

1. Wayner DS, Abrahamson JE. Learning to Hearing Again: An Audiologic Rehabilitation Curriculum Guide. 2nd ed. Latham, NY: Hear Again Inc (www.hearagainpublishing.com); 1998.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Donna S. Wayner, PhD; email: [email protected]; tel: (518) 786-3573.