This paper reviews some of the inherent issues when listening to music via hearing aid processing, and how the processing affects sound quality. Solutions implemented by manufacturers and set by clinicians through fitting software to improve the music listening experience are suggested. Current wireless options to promote music enjoyment with hearing devices are also described.

For the audiophile or avid music enthusiast, hearing instruments often fall short of expectations when aiming for high fidelity reproductions of musical inputs. The reasons for these shortfalls have been documented in the literature1,2 and are often associated with several key aspects of basic hearing aid function and traditional trade-offs in hearing aid design.

The perception of music—be it through amplification or via the unaided ear—is truly subjective in nature. As such, while a one-size-fits-all solution for improved music fidelity in hearing aids is attractive, the reality of creating such a solution is highly unlikely. Therefore, the clinician fitting musicians or music-lovers must have a keen grasp of the tools available to limit the impact of hearing aid processing on the music signal and create the highest fidelity reproduction of sound quality as possible.

This paper reviews some of the inherent issues when listening to music via hearing aid processing, and how the processing affects sound quality. Solutions implemented by manufacturers and used by clinicians via fitting software to improve the music listening experience are suggested. Current wireless options to promote music enjoyment with hearing devices are also described.

Tammara Stender, AuD, and Stephen A. Hallenbeck, AuD, are senior audiologists at the GN ReSound Global Audiology Center in Glenview, Ill. Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Dr Stender at:

Music and Audition

Music is a completely unique auditory experience that is universal to human culture. While speech and other environmental sounds are essential to verbal communication and awareness in one’s surroundings, music often encompasses a more emotional role. Music can elicit intense feelings of joy, sadness, and even love. It can bring people together when it is shared. It can evoke memories of yesteryear. It can fill people with excitement, inspire through evolving genres, and open minds to other cultures. Music is truly a special auditory phenomenon—and, as such, deserves special treatment when it comes to hearing aid processing.

Traditionally, music is treated the same as other sounds by hearing aid processing. A music program may be set up for a patient with slightly different gain settings, but often the features—such as digital feedback suppression—are set identically to the speech programs.

Yet music does not behave exactly like speech. It has distinct properties that separate it from other sounds in the environment.1 While speech has a generally controlled spectrum, the music spectrum is highly variable, based on the musical instrument. Music also has a wider, more variable range of dynamics than speech, and can reach higher intensities as well. The crest factor (the difference between the peaks in the spectrum and the average values) is about 6-8 dB higher for music than for speech.

Further, tonal qualities in music can occasionally mimic puretones when processed by the hearing instrument. These puretones can be confused as feedback by some feedback management systems, and the system may attempt to cancel them. This erroneous feedback designation and cancellation leads to artifacts, or additional tonal sounds emitted from the hearing aid. These artifacts, as they are unnatural to the sound environment, are often annoying to the hearing aid user and detract from the overall listening experience.

Enhancing Music Sound Quality with Hearing Aids

The topic of hearing aids and music reproduction has received good exposure over the last several years within HR and the academic literature. Some general findings can be divided into information that is utilized by hearing instrument manufacturers in their design process, or into techniques clinicians can use to manipulate output characteristics of the devices they are fitting.

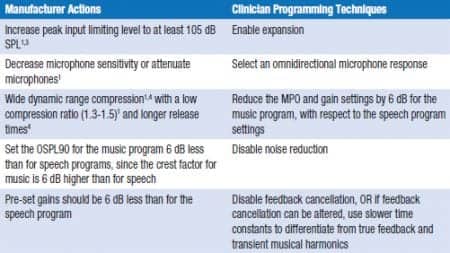

Table 1. Possible techniques to improve the representation of music in hearing aids, divided by manufacturer concerns (left column) and clinician programming options (right column), as described by Chasin5 unless otherwise stated.

Table 1 outlines aspects of hearing aids that can be altered to enhance the perception of music. The left column shows techniques that may be implemented by manufacturers, and the right column shows fine-tuning and programming adjustments that may be done by clinicians. Each of the proposed actions has the potential of improving the music listening experience for the hearing aid user.

Manufacturer strategies. From the manufacturer-responsibility column in Table 1, an increase in the peak input limiting level will reduce distortion at the front end of the hearing aid processing. A high input range up to 105 dB SPL will allow the forte dynamics and peaks in most music to pass into the hearing aid processer without distortion. If the hearing aid has a low input limiting threshold of less than 100 dB SPL, an input signal of 105 dB SPL will enter the hearing aid processing already distorted or clipped, and attempts to clean or optimize the signal will not be able to restore the original signal integrity.

Many hearing aids on the market have traditionally had an input limit of 85-90 dB SPL,1 although ReSound offers a peak input level around 105 dB SPL. Raising the input level reduces the occurrence of distortion due to clipping or limiting loud input signals. Similarly, decreasing the microphone sensitivity results in a lower overall output level from the microphone to the analog-to-digital converter, thereby reducing the amount of distortion at the input stage of the processing.

Figure 1. ReSound’s Unite wireless accessories that can be used for streaming music directly to the hearing instruments.

Clinician strategies. While improving the dynamic range helps provide the listener with a clean signal, other approaches to handling music include a “do-no-harm” strategy that increases the transparency of the hearing aid processing for the end user. Such strategies include enabling expansion, which reduces the internal noise of the hearing aid. Choosing an omnidirectional microphone response gives the least-altered sound experience and truest representation of the signal to the listener. Another strategy includes an overall gain reduction in music programs by approximately 6 dB.

Other recommendations to increase the transparency of the hearing aid processing include disabling noise reduction and feedback control.5 For this reason, the default setting in the music program for these two features is “off” for some hearing aids.

However, the feedback cancellation feature is often the trickiest to disable and still ensure a successful, feedback-free fitting. This is especially true when considering the frequency characteristics of a typical music-induced hearing loss, which may include a high-frequency noise notch. These hearing losses typically require their peak amplification in the 3-4 kHz region, which, coincidentally, is precisely the same frequency range where feedback is likely to occur. Thus, to reduce the occurrence of feedback while maintaining the integrity of the music signal, it is desirable to implement a feedback cancellation system designed especially for music.

Music And Hearing Aids Podcast

Listen to HR‘s 3-part podcast series on hearing aids and musicians that features viewpoints, sound samples, and PowerPoint presentations from Marshall Chasin, Larry Revit, and Mead Killion at: http://tinyurl.com/7s2bj3

A feedback control system that performs well for music would presumably analyze the input sound over a longer period of time, to allow for better accuracy in distinguishing true feedback from other tonal input sounds, like those found in music. Music often incorporates signals, such as flute and piano notes, that can seem very puretone-like and can be confused as feedback by the hearing aid. Traditional feedback systems will try to cancel these sounds, thereby introducing a disturbing, often tonal sound artifact. A feedback system tailored for music listening would be less aggressive in cancelling feedback than other speech-based systems.

Counseling plays an important role in the fitting of hearing instruments for musicians and audiophiles. Realistic expectations should be set, as with any fitting. While many hearing care professionals have a good handle on what users can realistically expect from their hearing aids in terms of listening to speech, they may feel less comfortable advising their clients regarding music.

Key concepts to highlight when counseling patients about music and hearing aids should include contrasting the listening needs and preferences for music compared to speech. Basic concepts such as the dynamics and the tonal characteristics of music compared to speech can be discussed. In the initial fitting, playing musical sound files or clips in real time through PC speakers can enhance patients’ understanding of the listening situations they will encounter.

Encouraging performance musicians to play their instruments while wearing their hearing instruments allows them to gain some experiential learning at the fitting session. Other counseling points might include instructions to patients regarding manual volume control options. For example, reducing the audio source (eg, stereo) volume while increasing the hearing instrument volume helps avoid clipping of an intense music input signal.1

Wireless Accessories and Music

With the advent of wireless technology in hearing aids, new options for music listening have been introduced. Wireless transmission via accessories to hearing instruments provides a wide range of benefits, including personalized ear-specific programming, mobility, and control specific to a music application. Wireless accessories can be specially programmed to meet the audio and/or music needs of the listener. This occurs as a separate program for the wireless accessory, without influencing any of the hearing instrument’s other speech or phone programs.

Wireless accessories function through wireless connections to adaptors, which are in turn connected either through wires or through Bluetooth to the audio source, such as a television, stereo, MP3 player, or smart phone. The user can activate wireless transmission of the signal through a push button on the hearing instrument or a remote control.

Options that work well for music include stationary audio streamers, phone accessories, and miniature microphone accessories. As an example, Figure 1 shows ReSound’s line of wireless accessories for optimizing the music listening experience. A stationary audio streamer, shown in Figure 1a, transmits sound from the television, home stereo, PC, or MP3 player to the hearing instruments. Figure 1b illustrates a phone accessory that streams music from a smart phone, as well as phone conversations in general. A miniature external microphone accessory (Figure 1c), when placed near the speaker of a stereo or other music source, streams the sound directly to the hearing instruments. Some of these devices also include a line input connection that allows for direct audio input into the audio source, such as an MP3 player.

Summary

Although most hearing aid technology is designed for optimal speech intelligibility, other sound inputs, such as music, can have a significant impact on the user’s experience. Music is different from speech in that it comprises a greater dynamic range and often contains tonal qualities.

For example, puretone-like sounds in music can easily be mistaken for feedback by traditional feedback control systems, which may then attempt to cancel them. This erroneous feedback cancellation results in sound artifacts that are detrimental to the overall sound quality.

Alterations to manufacturer and clinician-operated fitting software settings are important for the successful fitting of patients who listen to or play music. In addition, wireless accessories can introduce new avenues of music enjoyment through amplification.

References

- Chasin M, Russo FA. Hearing aids and music. Trends Amplif. 2004;8(4):35-47.

- Ryan J, Tewari S. A digital signal processor for musicians and audiophiles. Hearing Review. 2009;16(2):38-41.

- Chasin M. Hearing aids for musicians. Hearing Review. 2006;13(3):24-31. Available at: www.hearingreview.com/issues/articles/2006-03_02.asp

- Davies-Venn E, Souza P, Fabry D. Speech and music quality ratings for linear and non-linear hearing aid circuitry. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18:690-701.

- Chasin M. Music and hearing aids [PowerPoint slides]. American Academy of Audiology eAudiology course, Available at: eo2.commpartners.com/users/audio/session.php?id=2939

Citation for this article:

Stender T., Hallenbeck A.S. Setting the Score for Music and Hearing Aids Hearing Review. 2012;19(07):12-19.