The Platinum Rule states: “No one cares how much you know, until they know how much you care.” Nothing could be truer for hearing-impaired individuals. The interaction between the hearing care professional and the client is about expanding the client’s vision of what is possible. Nothing happens until the client is open to that vision. Dispensing professionals need to ask more of clients than the clients know how to ask of themselves.

The Platinum Rule states: “No one cares how much you know, until they know how much you care.” Although this may not be true for certain other health care professions, nothing could be more essential to the success of fitting hearing instruments.

Society seldom questions the medical prescriptions of physicians. When our ophthalmologist/optician informs us that we need glasses, bifocals or trifocals, we accept this diagnosis without question. When the dentist tells us that we need a crown or we have cavities that need to be filled, we are instructed to make an appointment with the receptionist on our way out of the office—and we do. Of all health care providers, hearing care professionals may be viewed by patients as the most elective.

Emotional Pain in Hearing Health Care

Carl Jung, one of the fathers of modern psychology, suggests that pain is a harbinger that must not be ignored. Jung postulated that, “If we do not answer the questions that pain asks, we will lose ourselves.” For the hearing-impaired patient, the evidence in the National Council On the Aging (NCOA) study1 is clear. Untreated hearing impairment can lead to a deep sense of alienation from friends and family, resulting in social isolation and emotional pain. If one chooses to withdraw from family, friends, and society in general due to their inability to connect with fellow human beings, the casualty is the self.

There is a “pain” amongst hearing health care providers that is also distressing. When a patient is diagnosed, and treatment is recommended, only to be rejected with the same excuses that patients have been using since the inception of amplification devices, there is great pain and frustration on the part of dedicated hearing care professionals.

This emotional pain on the part of the patient and the professional needs to be addressed in a meaningful and helpful way. The pain is asking questions that both parties need to explored with the same curiosity and tenacity with which technology pursues questions related to the damaged central auditory system. The answer to the question of patient reluctance does not live in circuitry or testing procedures, and to find the answers necessary to move this industry forward the hearing profession will have to look beyond the familiar turf of technology.

Focusing on Client Needs

“From everything I have read, learned (and continue to learn), and have been told by esteemed colleagues, I think it [counseling] could actually be the most important of all our skills. Our patients not only have damaged auditory systems, they also present with damaged self-concept, damaged self worth, and strained interpersonal relationships. For many of our patients, these latter issues are “front and center,” and until they feel emotionally supported and understood, our efforts to remediate their auditory systems will be stymied.”2

—Kris English, PhD, audiologist

In recent years, the industry has become intoxicated with the promise of technological advancements in hearing instruments and fitting software—and with good reason. The science that is now available to help hearing-impaired people has never been better. Dr. English and others2 have suggested that something is missing in our interaction with the patient, or at least that there is something that should be given greater consideration by dispensing professionals.

Hearing care professionals are well aware that the first-time patient who is not self-referred (i.e., comes in due to the urging of the spouse, children, etc.) is usually reluctant, skeptical, confused, uncertain and even angry in some cases. Add to this the fact that, on average, this reluctant patient has waited 7-10 years to finally see a hearing care professional, and it’s easy to see that the task before the hearing care professional is to somehow move this reticent patient toward hearing remediation —and do it inside the first appointment, which usually lasts one hour.

Can the kind of thinking that Dr. English advances have a productive impact on how hearing professionals interact with uncertain and skeptical patients? If so, what would this interaction look and sound like? Through seminars and talking with hearing care professionals, I have established a counseling protocol for approaching both first-time patients and previous users considering an upgrade in their hearing instruments:

- Realizing it is a huge step that the patient is in your office;

- Opening the patient (job one);

- Moving the patient toward ownership of the hearing problem;

- Determining the salient event;

- Listening to the story;

- Filling out the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI), and

- Addressing concerns and other issues.

Realizing it is a Huge Step that the Patient is in Your Office

The successful appointment starts inside the head and heart of the hearing care professional. The hearing care professional that realizes the importance of this first visit is ready to deal with the patient in a manner that makes it safe and secure for the uncertain patient.

It is no accident that the patient has chosen now to visit your clinic, regardless of what they say. This understanding by the hearing care professional is pivotal and will automatically set the above protocol in motion. If the hearing care professional fails to understand how important this appointment really is to the patient, the whole process is set adrift.

Given the hesitant nature of many patients, the curious hearing care professional instinctively wonders what it is that has brought the unwilling patient into their clinic. Automatic assumptions will only hinder the appointment. Regardless of what they say, the skeptical patient wants two things after you have earned their trust: hope and help. Otherwise their visit to your office makes no sense.

Opening the Patient (Job One!)

Logically, it is impossible to close something that is not open. When the hearing care professional allows him/herself to relax and concentrate on “opening the patient” by making the patient more receptive to the process, the rest will take care of itself. After all, when you are in a buying circumstance, do you want to be “closed?”

In his lecture, “The Narrative in Medicine” the great neurologist Oliver Sachs makes the following statement:

“There is never just a list of symptoms, there is never just a medical problem, there is the way it affects the person. There is never just a wound; there is a wounded individual. There is always a person in the middle of symptoms, and you need to get their story and their feelings and their metaphors.”

This may not be easy to do. Some people are bursting to tell their story. Others are reluctant and a delicate sort of “delivery”4 of the story is needed to fully understand and appreciate their histories.

The task of the hearing care professional at this stage is to evoke the story from the person and have them articulate their feelings about the hearing loss, at least as many as they will let out. It is frightening for a patient to reveal the depths of their own disability, whatever it is, and the fear engendered by it. One needs to go slowly, and so attentiveness, care and the willingness to understand become essential on the part of the listener! One of the ultimate compliments that is bestowed on a physician by patients is that he/she has a “good bedside manner.” To gain this compliment, the doctor needs one primary attribute: the compassion to be a good medical listener.

You are never more powerful in human interaction than when you are asking questions. You already know what you know. There is little that you may learn as you are telling, advising and educating the patient. It is the patient that the hearing care professional must learn about. Questions are more than the key to good and helpful interaction with the patient; questions are the answer. This is the heart of counseling.

With the utmost respect for hearing care professionals intended, counseling is one of the most misunderstood words in the lexicon of the field. Think of the patient as a basket. When you are putting something into the basket, you are not allowing the patient to be involved in the process. When you are putting information into the basket, the patient’s role is passive. When you are taking information out of the basket, you are both involving the patient and learning about them at the same time. Telling, advising and educating are deposits that the hearing care professional makes in good faith into the basket of the patient. Seldom is this approach fruitful with the reluctant patient who has come into the office to please someone else. Do not confuse educating with counseling.

There will be an appropriate time to tell, advise and educate the patient, but this time is not at the beginning of the appointment, and not until the patient has taken ownership of their visit to your practice/clinic. There is no doubt that, as a hearing professional, you know more than the patient does about instrumentation, the central auditory system and the societal drawbacks of doing nothing about ones hearing impairment. What you know does not matter much to a patient who is not comfortable with you and thinks that your only motive is to sell them a hearing aid.

The power of the basket analogy is this: when you are putting information into the patient’s basket, there is no need for participation on the part of the reluctant patient. Friends and family have been putting information into their basket for sometime, and it has worn thin. When you are asking questions and the patient is encouraged to participate in the process, a whole new understanding on the part of both the patient and the professional begins to emerge. As you become clearer about what the patient’s life circumstances are and what the patient wants, believe it or not, so does the patient. It is only then that you will be allowed to help.

At this point, we should review the Platinum Rule: “No one cares how much you know, until they know how much you care.” Trust is built by showing care. Telling, advising, testing and educating at the beginning of the appointment will not build trust. Remember: in most cases, the patient does not want to be in your office, and being a tidal wave of information will only serve to swamp him/her.

Telling, advising and educating the patient are the natural inclinations of the practitioner who is eager to be of service, wants the patient to be aware of their professionalism and feels the need to empower the patient with confidence. The professional also has a natural tendency to avoid awkward moments of silence while trying to formulate the next question. So, all too often, professionals find it easier to talk than to listen to their patients.

Moving the Patient Toward Ownership of the Problem

Establishing ownership of one’s hearing impairment is paramount to the successful appointment. As long as the patient feels that they are in your office for someone else, there will be no personal investment in how the appointment goes. In fact, unresolved thinking about the hearing impairment will serve to sabotage the appointment at every turn.

Hearing Care Professional (HCP): “Mr. Jones, whose idea was it that you come see a hearing professional today?”

This question is huge because, in an instant, the patient will tell who referred them or if they are self referred. This information gives the hearing professional something concrete to work with.

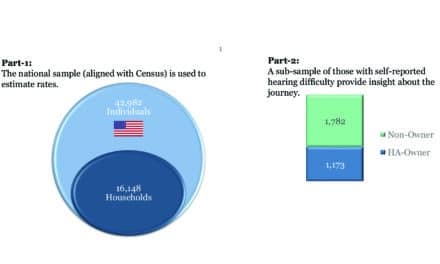

The 2000 HR Dispenser Survey5 indicates that 69% of hearing instrument specialists’ patients and 76% of dispensing audiologists patients come at the urging of someone else (Table 1). In other words, these patients do not own, nor in most cases are they personally invested in seeking, a viable solution to their hearing health care needs. They have come to the hearing care office to placate someone else.

Regardless of the level of impairment, without personal ownership of that impairment, the patient’s willingness to do something is close to zero. Example dialogue:

Hearing Care Professional (HCP): Mr. Jones, whose idea was it that you come see a hearing care professional today?

Jones: It was my wife’s idea. She is constantly on my case about my hearing. I think, however, she is the one with the problem because she mumbles all the time.

HCP: Is this communication issue

creating difficulty in your relationship? [This is a fair and honest question, and moves the dialogue to the heart of the matter.]Jones: Well, I’d say so, she just won’t get off my back about this hearing thing.

HCP: Is this whole matter of communication between your wife and you troubling to you, Mr. Jones?

Jones: Yes, it is really starting to cause some problems.

Remember that Mr. Jones has come for two things, hope and help, regardless of what he says, and it is huge credit to his character that he is in your office! If the wife is present during the initial appointment, this can be of immeasurable help.

HCP: Mrs. Jones, what is your hope in all of this?

Mrs. Jones: I love my husband, but over the past few years our lives have changed dramatically. We no longer go out to eat, or to the show or even to parties that our friends give because he has so much trouble following conversations. Even at home he often struggles to hear me when there is any other noise going on like the TV or radio.

HCP: Mr. Jones, have you grown tired of the struggle of trying to understand what is going on around you, whether others are mumbling or not?

Jones: Yes.

HCP: So would it be fair to say that you have also come to my office for yourself?

Jones: Yes.

When the goal is moving a patient toward ownership of his/her condition, the path to that will be as individualized as each dispenser. The path will give the dispenser a sense of direction and provide each dispenser a sense of coherency during the interview process. If ownership is not established, what hope does the hearing care professional really have that they will be allowed to help the patient? Paradoxically, the patient who does not know how to open him/herself to the process will be left hopeless if the dispensing professional does not move him/her to ownership of the office visit.

| HIS | DA | Avg. | |

| Self-motivation | 31% | 24% | 28% |

| Spouse | 32 | 22 | 28 |

| Physician | 9 | 28 | 18 |

| Children | 12 | 13 | 12 |

| Friend | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| Other | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| HIS: Hearing instrument specialists DA: Dispensing audiologists |

|||

| Table 1. Responses by dispensing professionals to the question: “What percentage of patients/clients came into your office primarily because of…”5 | |||

The Salient Event

In the above example, Mr. Jones has indicated that his wife has been concerned about his hearing for some time, even though he uses the phrases “constantly on my case,” and “just won’t get off my back.” It is clear to the hearing care professional that this issue about Mr. Jones hearing is not new, and it is taking its toll on the relationship.

Because hearing care professionals know that the average reluctant patient has waited 7-10 years before doing something about their hearing loss, there is no reason to assume that this is not true in Mr. Jones case also. There is, however, some hidden power in this moment for the professional and patient alike. The power lives in the salient event: the event that motivated the patient to finally come in after all of these years and face their auditory demons.

To ask, “Well, Mr. Jones, what happened?” is to compromise this crossroads in the interview process. In this counseling protocol, opening the patient with questions and moving them to ownership is the “cake” of ownership, and the salient event, the story, concerns and the COSI are the icing on that cake.

Let us look at how the salient event can be teased out so that the patient can continue to reinforce the ownership of their hearing difficulties and their visit to the clinic. The hearing care professional now paraphrases the conversation with the patient:

HCP: Mr. Jones, you have indicated that Mrs. Jones has been after you for some time about her concerns about your hearing. Do I have that right?

Jones: Yes you certainly do!

HCP: How many years would you say that your ability to hear has been an issue with your wife?

Jones: Several.

HCP: I see that the appointment was made yesterday. Who made that appointment?

Jones: My wife did.

HCP: What was there about yesterday that you allowed her to make the appointment and you chose to keep it? [Here comes the salient event.]

Jones: Well, yesterday we were invited to the 50th wedding anniversary of our best friends. I told my wife that I just didn’t enjoy large gatherings because everyone was always talking at once, and it just wasn’t any fun for me to be there. Gloria and I got into the biggest fight we’ve ever had. She said some pretty tough things to me.

HCP: So, Mr. Jones, how did you go from that fight to my office?

Jones: Well, “we” decided that, if there was a problem, maybe I should look into it and see if there is anything that I can do.

HCP (paraphrasing): So, from what you are telling me, it would seem that solving this communication problem that exists between you and your wife is of real importance to you.

Jones: Yes, it really is.

At this point, the patient is not only owning the auditory circumstance he finds himself in, but he is also owning the consequences of doing nothing about those circumstances.

The Story

The story encompasses the difficulties that the patient has been having over the years in his/her own words:

HCP: Mr. Jones, your wife said that you no longer go out to eat or to social gatherings like you once did and you don’t even go to the movies anymore. What do you miss most about that?

At this point, Mr. Jones is a wide open book. In all likelihood, he has told the hearing care professional far more than he originally intended to (and possibly more than he formerly would admit to himself) and trust has been subtly built between you. Mr. Jones is much more likely now to add to the story by telling what he has lost in terms of social interaction and what price he has paid. All of this will simply be Mr. Jones convincing himself that it is now time to do something to change the circumstance of his life. The hearing care professional has become a facilitator in helping Mr. Jones empower himself.

COSI

The Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI)6 is a simple form that helps identify amplification goals and the environments in which the patient struggles to understand what they hear. These environments are identified by the patient and add further ownership to this entire process. Equally important, when the patient returns for adjustment of their hearing instruments, you can check the COSI form and ask them the items that were previously identified as difficult listening situations.

Concerns and Other Issues

Concerns may come up in the telling of the story. Mr. Jones may mention that he knows someone who bought hearing aids and does not use them. In these cases, the hearing care professional must be able to understand what the patient is not saying:

HCP: Mr. Jones, is it your concern that the same thing might happen to you? [Note: the issue at this point needs to be addressed so that the patient can let go of it.]

Jones: It has crossed my mind.

HCP: Mr. Jones, I am not familiar with your friend’s circumstance. However, if we should determine after testing that I can help you, here is how I will deal with your adjustment to hearing aids….

Once the patient is open to the process and participates in the process, the chance that he/she will positively address the hearing loss (e.g., through amplification) is greatly increased. With this approach, more patients will be open to what hearing instruments can do for them. At this point, the potential user has already taken ownership of the hearing impairment.

Conclusion

In the past, the job of the hearing care professional was to identify the problem, recommend a solution and supervise implementation. This approach creates a passive patient who listens politely and then often leaves the office untreated. If the hearing care professional does not create responsiveness, which is a willingness to participate and grow on the part of the patient, the patient is left to defend what they already think, feel and do.

Acceptance of a hearing problem, and acceptance of hearing instruments, is a courageous act on the part of the patient. Hearing care professionals need to help the patient summon that courage—not by telling the patient what to do or think, but rather for the patient to come up with his/her own answers with the aid of professional listening and question-asking.

At its best, the interaction between the hearing care professional and the patient is about expanding the patient’s vision of what is possible. Nothing will happen until the patient is open to such a vision. Hearing care professionals must ask more of the patients than the patients know how to ask of themselves.

Von Hansen is a business and communications consultant and lecturer on hearing health care issues. He lectures extensively throughout the U.S. on counseling issues, and this article was adapted from a semiar presented by him to the American Conference of Audioprosthology. His business is located in Lebanon, OR.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Von Hansen, 1773 Post St., Lebanon, OR 97355; email: [email protected]; tel: (541) 259-1550.

References

1. Kochkin S & Rogin C: Quantifying the obvious: The impact of hearing instruments on quality of life. Hearing Review 2000; 7 (1): 6-34.

2. English K:Personal adjustment counseling: It’s an essential skill. Hear Jour 2000; 53 (10): 10-16.

3. Strom KE: Don’t lose sight of the benefits. Hearing Review 2001; 8 (1): 10.

4. McSpaden JB: The obstetric delivery of the patient’s story. Hearing Rev 1998; 5 (9): 16-24.

5. Skafte MD: 1999 hearing instrument market—The dispensers’ perspective. Hearing Review 2000; 7 (6): 8-40.

6. Dillon H, Birtles G & Lovegrove R: Measuring the outcomes of a national rehabilitation program: Normative data for the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and the Hearing Aid User’s Questionnaire (HAUQ). J Amer Acad Audiol 1999; 10: 67-79.