Interventional Audiology Services: Patient Complexity & Time | October 2016 Hearing Review

Differentiating hearing care treatment plans based on the complexity of the patient

Every hearing care professional is well aware that some patients require substantially more clinical time, counseling, hearing aid adjustment, etc, than others. In many cases, the indicators for patients who need more help are fairly obvious and predictable: more severe hearing loss, cognitive decline, physical limitations, dexterity problems, etc. Yet, the traditional model for serving patients allows for little differentiation for these factors, which may end up being unfair to both the consumer and the clinician.

For generations, hearing care professionals have not effectively differentiated their treatment and management of sensorineural hearing loss in adults. Regardless of the magnitude of hearing loss, cognitive ability, and other non-audiological variables, hearing care professionals have traditionally offered the motivated adult patients hearing aids—usually striated along three or four technology levels—as the sole treatment option.

Besides the multiple levels of technology, which according to recent independent research indicates premium technology may not result in superior patient outcomes for “typical” hearing losses,1,2 the professional time required to manage all aspects of hearing handicap is usually bundled into the price of the products dispensed. Essentially, all patients who are receiving treatment are paying for the same thing—even those individuals who don’t want or need the additional service time.

To confuse matters, there are individuals on the other end of the spectrum—many of whom are older with multiple chronic disabilities—who require additional clinical time due to the complexity of their treatment plan. This undifferentiated approach, where professional time is bundled into the fee for products offered to all patients, has led many outside the industry to question the value of the professional services we provide.3

In addition to not seeing the value of professional services when they are bundled into the sale of hearing aids, there is at least one other reason to question the traditional approach of exclusively offering multiple levels of hearing aid technology to adults with hearing loss: Patients with mild loss and normal cognitive and physical ability require less clinical time than patients with greater hearing loss and/or significant cognitive or physical impairments.

In order to appreciate this shortcoming of the current service delivery model, consider these two examples:

Patient A: A 65-year-old male with no history of ear disease or noise exposure, a mild high-frequency hearing loss and normal cognitive and physical function is offered a choice of three hearing aid technology levels. The cost of the devices includes unlimited office visits for one year. Given the situational communication problems of Patient A, a pair of $6,000 premium hearing aids are recommended because he is an active individual who needs aggressive noise strategies for his primary communication complaint. He utilizes 3 clinical hours of professional time in the first year.

Patient B: An 80-year-old male with no history of ear disease or noise exposure, a moderate loss, and declining cognitive and physical functioning is offered a choice of three hearing aid technology levels. The cost of the devices includes unlimited office visits for one year. Because our 80-year-old is less active, a set of $5,000 mid-level hearing aids are recommended. Considering the long-standing hearing loss combined with memory problems and other physical ailments, Patient B and his family believe they are receiving a great value, especially for all the time you will be spending with him. He utilizes 6 clinical hours of professional time in the first year.

The inefficiency of our delivery model is reflected in the fact that Patient A, purchasing a high-end hearing aid and utilizing only 3 clinical hours, provides an extremely high return per clinical hour on a treatment plan that is not complex. Patient B, who requires a considerably more complex treatment plan, consumes twice the clinical time and provides a relatively low return per clinical hour.

It could be argued that Patient A subsidized part of Patient B’s treatment. That being said, the real tragedy occurs when Patient A rejects the recommendation of high-tech hearing aids based on lifestyle because he doesn’t feel he has a $6,000 problem—a problem he considers “normal for his age.” In that scenario, Patient A loses and the clinic is left with a potentially unhealthy economic situation, as well as the potential loss of a loyal customer and good referral source.

Today’s delivery model treats both patients the same: A clinic-based model in which both patients (or a third-party payer) are buying the same thing, even though some of the technology or services may not be needed. Patient A with a mild loss, for example, is likely to require audibility of missing high frequency speech cues. And, since he has normal cognitive and physical functions, chances are good his communication difficulties can be resolved with relatively little professional time. Further, relatively traditional amplification schemes, designed to provide optimal gain for soft and average inputs, may be appropriate for someone like Patient A.4 Today, this technology can be found in low-end hearing aids (and some high-end PSAPs), which could be purchased over-the-counter, online, or through the dispensing professional using a pay-as-you-go service model.5

On the other hand, Patient B has a more complex problem requiring substantial professional time and probably more sophisticated technology. Patient B will need more assistance learning how to insert his hearing aid and to understand the use of automated wireless technology—features needed to improve his declining signal-to-noise (SNR) loss and/or reduced cognitive and physical abilities. He will need to be counseled on how hearing loss and cognitive deficits affect his ability to communicate.

It should be acknowledged that the typical patient is not as straightforward as these examples. There are plenty of patients with milder losses and poor cognition, or severe losses and normal cognitive ability. Additionally, there can be other co-morbidities and factors that complicate treatment plans. Our point is that additional testing that evaluates downstream, non-audiological variables would help to stratify treatment approaches along both the professional time and hearing technology domains.

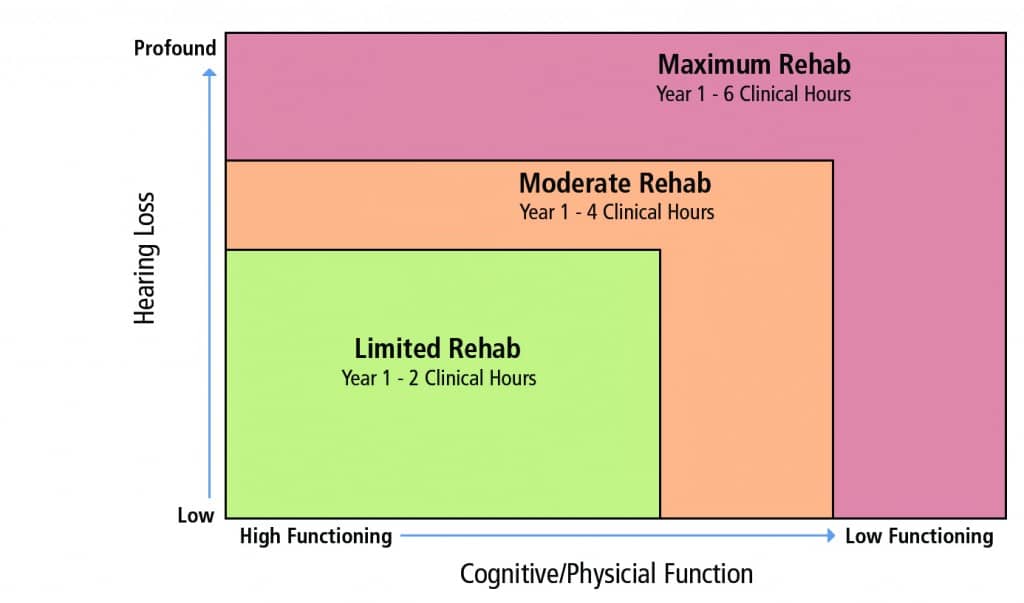

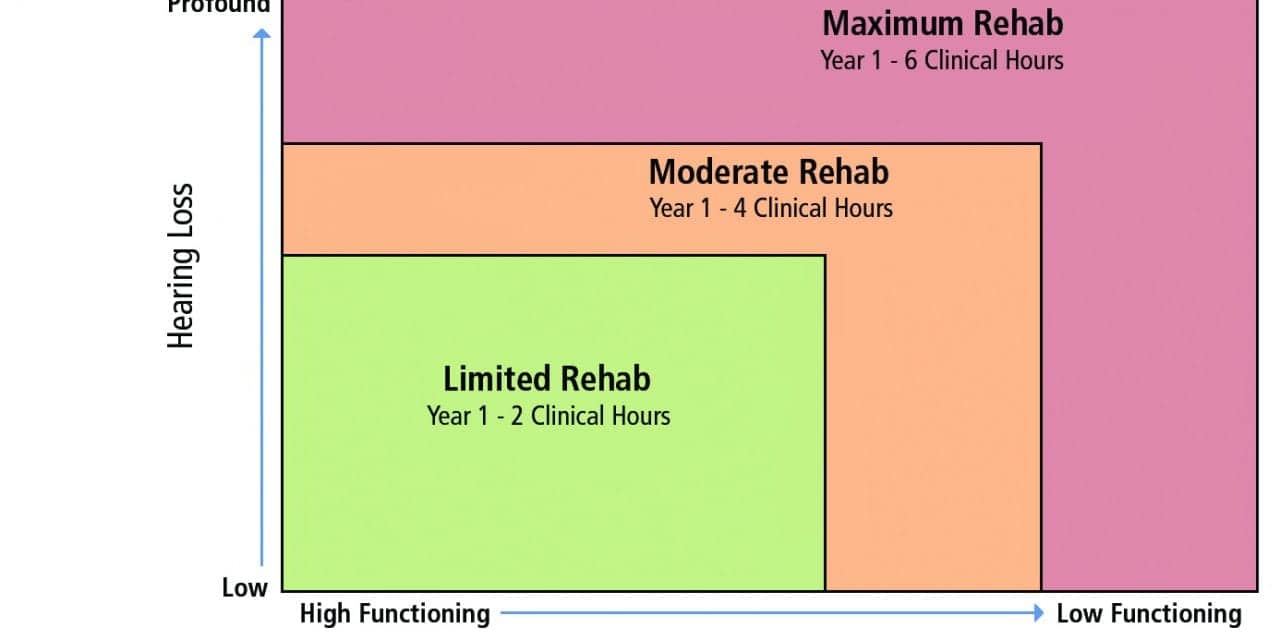

Figure 1. Example illustrating the severity of two patient variables (degree of hearing loss and cognitive/physical function) and how these might influence the number of required clinical hours for the hearing care professional during a first-time hearing aid fitting.

A different approach that adds remote tele-audiology services or alternative products, such as high-quality starter hearing aids (or PSAP-like devices), might look like this: A comprehensive diagnostic and functional communication assessment is completed on all patients. This battery of procedures includes traditional audiological tests to rule out medical problems, as well as tests that screen for cognitive decline and physical conditions. Given that 71% of individuals over the age of 80, a group comprising of a significant portion of many hearing care professional’s caseload, has a disability,6 it seems logical to screen for some of these other co-morbid conditions.

A new approach, one not based so heavily on pure-tone thresholds and patient lifestyle to determine hearing aid candidacy, might look like Figure 1, where:

Level 1: Mild hearing loss and/or normal cognitive & physical function. The goal of audiological intervention is to optimize audibility and improve the listener’s SNR using the most cost-effective approach possible. Many of these patients could be good candidates for high-quality off-the-shelf solutions with only minimal interaction with the hearing care professional.

Level 2: Moderate hearing loss and/or mild decline in cognitive & physical function. The goal of audiological intervention is also to optimize audibility and improve the listener’s SNR across all relevant situations. However, considering the increasing complexity of the problem, advanced hearing aid technology might be needed. In addition, given their functional cognitive and/or physical decline, more professional time might be needed to manage their communication problem.

Level 3: Severe hearing loss and/or marked decline in cognitive & physical function. Like a Level 2 patient, the goal of audiological intervention is to optimize audibility and improve the listener’s SNR across all relevant situations, which often requires advanced hearing aid technology. Because of the marked decline in their auditory and cognitive systems, the Level 3 patient is likely to require substantially more professional time.

The increase in clinical time should be reflected in the cost to deliver an effective treatment plan for each individual. Recently published hearing loss prevalence data indicates there is a large potential market for Level 1 service delivery. According to the analysis, more than 66.5% of the American population with bilateral hearing impairment (38.17 million) has a mild hearing loss.7 Since it cannot be determined from this study the number of individuals with mild hearing loss who suffer from cognitive or physical decline, the prevalence of these co-morbid conditions could be determined during a comprehensive evaluation, like the kind we suggest. Clearly, more research is needed to understand the interconnectedness of hearing loss, cognition, physical decline, aging, and the most appropriate course of audiological treatment and management for patients.

Using a striated approach to treatment and management of communication difficulties, as outlined here, is an opportunity for hearing care professionals to specialize and tailor their protocols to better meet the wide range of patient needs. Using this model, it is possible to envision a future in which Level 1 patients are treated via tele-practice (possibly by technicians), while Level 2 and Level 3 patients receive more comprehensive audiological care, including the delivery of sophisticated treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy or personal adjustment counseling.

Adding additional measures beyond our traditional audiological testing could help provide a better picture of what is required clinically and technologically to provide the most effective treatment plan for individual patients. With a better understanding of the complexity of the treatment needed for a good outcome, a plan can be developed that is time- and cost-appropriate for the patient and professional alike. Given the changes in healthcare and advances in technology, as a profession, we need to constantly review our treatment delivery systems and look for models that enhance outcomes for our patients and advancement of our profession.

References

-

Cox RM, Johnson JA, Xu J. Impact of hearing aid technology on outcomes in daily life I: The patient’s perspective. Ear Hear. 2016; 37(4)[Jul-Aug]:e224-37

-

Johnson JA, Xu J, Cox RM. Impact of hearing aid technology on outcomes in daily life II: Speech understanding and listening effort. Ear Hear. 73(5):529-540.

-

National Academy of Sciences (NAS). Hearing Health Care for Adults: Priorities for Improving Access and Affordability. June 2, 2016. Available at http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2016/Hearing-Health-Care-for-Adults.aspx

-

Killion C, Friket-Pasa S. The 3 types of sensori-neural hearing loss: Loudness and intelligibility considerations. Hear Jour. 1993;46(11):31-36.

-

Quall D. How low can you go? Practical considerations when offering a low-priced hearing aid [webinar]. March 23, 2016. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2016/03/webinar-low-can-go-practical-considerations-offering-low-priced-hearing-aid

-

Jorgensen LE, Palmer CV, Pratt S, Erickson KI, Moncrieff D. The effect of decreased audibility on MMSE performance: A measure commonly used for diagnosing dementia. J Am Acad Audiol. 2016;27(4):311-323.

-

Goman AM, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am J Pub Health. Published online August 23, 2016. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27552261

Dan Quall, MS, is Director of Managed Health Services for Fuel Medical Group, Camas, Wash, and has worked since the 1970s in private practice, dispensing networks, and hearing aid manufacturing.

Brian Taylor, AuD, is Senior Director of Clinical Affairs at Turtle Beach Corp, San Diego, and serves as a Clinical Advisor for Fuel Medical Group in Portland, Ore.

Correspondence can be addressed to Dan Quall at: [email protected]

Original citation for this article: Quall D, Taylor B. Patient Complexity and Professional Time: Improving Efficiencies in the Service Model. Hearing Review. 2016;23(10):42.?

Other Articles in This Special Edition about Interventional Audiology Services:

Introduction: Interventional Audiology Services: Meeting the Demands of Today’s Consumer, by Brian Taylor, AuD, Guest Editor

What Hearing Care Professionals Need to Know About Today’s Healthcare Economics, By John Bakke, MD, MBA

Intervening in the Care of More Patients: Beyond Clinic-based Testing and Fitting, by Brian Taylor, AuD

Incorporating Health Literacy into Your Hearing Care Practice, by Jennifer Gilligan, AuD, and Barbara E. Weinstein, PhD

Patient Engagement Through Interventional Counseling and Physician Outreach, by Robert Tysoe

Thinking Outside the Booth: Three Overlapping Categories of University Audiology Outreach, By Melanie Buhr-Lawler, AuD

Layering the level of patient and service offered seems a sensible next step towards a more transparent offering but I think that the treatment cannot just be measured in hours.

What about offering the customer a detailed programme that clearly defines how the additional time will be spent?

To take this even further, why not provide an entirely personalised treatment plan, after an in-depth assessment? Not all physical disabilities require the same time to address e.g. a patient who has both visual impairment and dexterity issues might require different education and orientation than a customer with a mild memory problem.

I think that if customers have to pay for hearing rehabilitation services there needs to be more transparency in the way these services are delivered. It is difficult for a customer to commit to a premium plan just on pure trust.

Thank you for an excellent article. I could not agree more with the sentiments.

I would also like to see more mention of phone applications, auditory processing, ALDs, cochlear implants, auditory prosthetic devices in these types of discussions.

My concern though is implementing this in a managed care paradigm, in a bundled, hearing aid delivery model and/or in a world of “free”.

This type and level of evaluation and management requires a different approach to the product and how it is delivered and priced.

I hope to continue to see more discussion on implementation of this fantastic, patient centered idea.