SPECIAL REPORT | July 2017 Hearing Review

Updated June 14, 2017

By Karl Strom, editor

The NASEM meeting’s proposals are not part of the FDA’s formal rule-making process, but they could serve as a starting point for considerations by FDA and its discussions with stakeholders when formulating a new OTC hearing device classification. The “National Academies’ Hearing Health Care Report: June 2017 Dissemination Meeting” was held at the Keck Center in Washington, DC, on June 9 and was also made available via a live webcast.

Technical and Quality Standards for an OTC Hearing Device

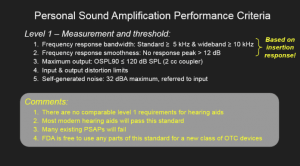

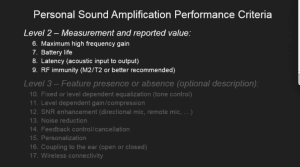

In the morning session, Bill Rabinowitz, manager of acoustic research at Bose, played a prominent role in the NASEM presentation and outlined the Personal Sound Amplification Performance Criteria (ANSI/CTA 2051) developed for PSAPs by a committee at the Consumer Technology Association (CTA, formerly CEA) chaired by Poppy Crum, PhD, of Dolby Labs and Mead Killion, PhD, of Etymotic Research. Rabinowitz outlined the voluntary standard, and he explained how the criteria delineates between three levels of performance features: Level 1 has defined measurement procedures and specific minimum/maximum values for compliance (eg, distortion limits); Level 2 has defined measurement procedures with only a reported value for evaluation (eg, battery life); and Level 3 has only the identification of a feature (eg, noise reduction) with any details/measurements being left up to the manufacturer/distributor.

Within Level 1 are proposed requirements for PSAPs based on insertion response for frequency bandwidth (with “standard” being defined as ?5kHz, and “wideband” ?10 kHz), frequency response smoothness (no response peak >12 dB), maximum output (OSPL90 in a 2cc coupler ?120 dB SPL), with input/output distortion and self-generated noise (32 dBA) limits. Rabinowitz said that, although there are no established comparable requirements for hearing aids, most hearing aids and some PSAPs would pass this standard. Within Level 2, the standard includes maximum high frequency gain, battery life, signal latency/delay, and RF immunity (M2/T2 or better recommended). Level 3 could include descriptions of many different features like tone control, SNR enhancement, feedback and noise reduction, wireless coupling, etc. He emphasized that the FDA should feel free to “cut and paste” or modify any parts of the CTA standard when formulating requirements for a new OTC device category.

Within Level 1 are proposed requirements for PSAPs based on insertion response for frequency bandwidth (with “standard” being defined as ?5kHz, and “wideband” ?10 kHz), frequency response smoothness (no response peak >12 dB), maximum output (OSPL90 in a 2cc coupler ?120 dB SPL), with input/output distortion and self-generated noise (32 dBA) limits. Rabinowitz said that, although there are no established comparable requirements for hearing aids, most hearing aids and some PSAPs would pass this standard. Within Level 2, the standard includes maximum high frequency gain, battery life, signal latency/delay, and RF immunity (M2/T2 or better recommended). Level 3 could include descriptions of many different features like tone control, SNR enhancement, feedback and noise reduction, wireless coupling, etc. He emphasized that the FDA should feel free to “cut and paste” or modify any parts of the CTA standard when formulating requirements for a new OTC device category.

As he did at the FTC’s April 18 workshop, Bill Belt of the CTA made a case for creating a logo that would signify compliance to the CTA voluntary standard. He reminded attendees that any OTC device packaging would be very small—about the size of cell phone box or smaller—making the “real estate” on the package incredibly valuable. A logo signifying compliance with the CTA 2051 standard for minimum performance requirements for personal sound amplifiers, similar to a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval” by the CTA, would help a consumer identify high quality products, says Belt.

Consumer-facing Labeling

So what should go inside or outside of the packaging on an OTC hearing device? Committee member and audiologist, Judy Dubno, PhD, said that, when looking for a device, there needs to exist some method for consumers to meaningfully assess performance, as well as some minimum standards to measure and guarantee audibility. “For example, what does the consumer need to know to make informed choices for any hearing aid?” asked Dubno. “…What do they need to know to choose one product from another? [The Committee] focused on the fact that it’s very difficult to compare features, and an important message to be able to get to consumers is that, when they are choosing hearing aids, it needs to be lifestyle-based. If you’re going to sit in your home and watch television, you may want one kind of product; if you’re going to be out and about in meetings and be active in loud and crowded spaces you may need a different kind of a product…You need to have an environmentally, lifestyle-based choice.” She also said that, when consumers assess aspects of price and quality (equaling value), there can be different tradeoffs involved.

Later in the day, it was suggested by Brenda Battat of the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA) and Bray that it would be helpful if a “hearing loss matrix” could be used based on a person’s audiometric configuration, along with other factors, for finding an appropriate hearing device. In this way, a person’s specific needs and hearing loss might be matched to an appropriate type of product.

Labeling that informs consumers of the complexities surrounding a sensorineural hearing loss was also advocated by hearing care professionals and the hearing industry. Rick Giles, ACA, BC-HIS, of the International Hearing Society (IHS) noted that sensitivity to loud sounds (ie, recruitment) is an issue consumers should be aware of. Harvey Abrams, PhD, a consultant for the Hearing Industries Association (HIA), suggested that a nod to professional fitting should appear on the labeling, since NASEM’s own report says that “proper training and fitting are complex but necessary elements of maximizing performance among users of hearing devices. Consumers who work with providers trained in the use of properly prescribed and fitted hearing devices can expect better results than those who use off-the-shelf products.”

Thomas Tedeschi, AuD, of Amplifon and others noted that the labeling should prominently emphasize that, if consumers try the OTC device and are unsuccessful, they should seek help from a qualified hearing healthcare professional. There should also be a means for returning the product if it doesn’t work. “…If it costs them a lot of money to have an unsuccessful trial, then the thing we worry about is…if it goes in the drawer, they may wait another year or two before they seek proper attention,” said Tedeschi. “So maybe we can move that from the bottom to the top [of the labeling].”

David Zapala, PhD, a NASEM Committee member and an audiologist at the Mayo Clinic, also cautioned about making claims about what an OTC product can do, while stressing the consumer should “Get your hearing tested”—a phrase recommended by one of the breakout session groups as a ubiquitous marketing rallying cry for the hearing healthcare field. “When you use an over-the-counter device,” said Zapala, “it’s going to be an experiential thing; it’s going to be an experiment. It either works or doesn’t work. And that’s why we were concerned about the consumer being knowledgeable about when they can turn that hearing device back in and get a refund, because there’s really no way to predict, without evidence from a hearing test…whether that’s going to be a successful fit or not.”

Alissa Parady, director of government affairs at IHS, lauded how the NASEM report specifically referenced the potential new OTC class of products as “wearable hearing devices” and not “hearing aids.” She said there may be confusion by consumers about the two types of devices intended for the same purpose but potentially regulated in different ways and offered with a different level of consumer protection.

Health Risks

Obviously, any factors regarding health and safety—particularly those referred to as “red-flag conditions”— will play an enormous role in the deliberations by the FDA relative to a new OTC device category. Abrams pointed out that consumers should be aware of problems that can crop up after the use of an OTC device, as well. “[Labeling should convey that] if you have any of the following conditions, don’t buy this device…and you should see a physician specializing in the diseases of the ear prior to purchasing this device. Then, if you’re wearing this device, and any of these red-flag conditions [occur]…you should also be advised to seek the advice of an ear specialist.”

Parady pointed out a recent pilot study by Amplifon that suggests only 1 in 4 people successfully identified their level of hearing loss, and she noted that the number of medical referrals has consistently been trivialized by OTC device proponents. “Presuming that there are about 30 million people [in the US] with hearing loss, about 12%…need to get a referral based on the FDA red flags or some other sort of indication,” said Parady. “This amounts to more than 1.4 million people. This is not an insignificant number that we’re talking about.” Tinnitus and vestibular problems leading to falls, and their relationship to hearing loss were also mentioned as real medical conditions that complicate OTC hearing device use.

However, Rabinowitz cautioned against using a plethora of negative consumer warnings in the labeling of an OTC hearing device or over-reliance on technical definitions. “I want to reframe this a little. A lot of the reason we are here and the reports that we have is because people aren’t coming into the system. If we put things on a box that [urge people to] go into the traditional route of the system, you’re basically discouraging people. I think the other thing that came out of the [NASEM] report is that the risk levels people face—even these red-flag conditions—they’re very important if they happen to you, but [the red-flags are] of significantly low incidence that we need to get people to try things. So concern about what the technical definition of the word ‘muffling’ means is totally different [for a consumer versus an audiologist or engineer]. We have to be in the mindset of what’s going to help consumers; what needs to be on the box to help consumers to take some action, because they ain’t taking it now.”

Douglas Beck, AuD, of Oticon countered that a deeper dive into the statistics of hearing loss reveal a more nuanced picture of hearing aid use. He said the fact that someone has a hearing loss does not necessarily mean they would want or benefit from hearing aids. He cited a recent study by Amlani and Valente pointing out that, in European and Scandinavian countries where hearing aids are free, only about 40% of people with hearing loss use them. “In the US it’s 33%,” said Beck. “I’m not doubting that there are people who would like hearing aids and can’t get them; that’s not even a discussion. But it’s not like we’re a million miles behind. We’re actually doing some very good things, making hearing aids available at many different price points. Price is a factor, clearly. But among the other factors is that it should be about hearing healthcare, not about trying something.”

Safety Risks & Fitting Concerns

There was considerable debate and some confusion at the meeting regarding the 120 dB upper limit for peak sound levels, eartips, frequency response, as well discussions about compression and wireless requirements. Beck pointed out that many of the specifications for hearing aids are created by working groups like ANSI. “It would make sense to have a group of this sort,” said Beck, “because [the specifications] depend on what the instrument is, who made it, what it’s capable of, and who it’s intended for…If we go one-by-one over these [proposed CTA standards], distortion and noise levels should be as low as possible, latency as fast as possible, frequency response characteristics should be shown, bandwidth should be [at] 8,000-10,000 Hz…I think this is a working group task based on [if] this is a hearing aid for [a mild versus moderate] hearing loss.”

In particular, the 120 dB maximum output (OSPL90 in a 2cc coupler) of the device drew considerable concern and confusion. “The 120 dB SPL—assuming it’s an A rating—is extremely loud,” continued Beck. “Very few people in this room would listen to it. So, if we have a mild loss, I think that’s way more than we need. I think we could talk more about 80-90 dB as a maximum, and for a moderate loss maybe we could go up to 100 dB. But [120 dB] is an awful lot of sound, and I don’t think anybody with a mild loss in this room would be comfortable [with it as an upper limit]. Beck also pointed out that the NIOSH recommended noise limit is 85 dBA for 8 hours, while people typically wear hearing aids for 8-14+ hours a day.

Rick Giles of IHS said that he has encountered people in his hearing care office who have experienced significant threshold shifts after wearing PSAP-like devices that offer 120-130 dB of amplification. “This is entirely too much sound for a person with mild-to-moderate hearing loss. I’m thinking a maximum 105 dB output would be more than enough for a moderate hearing loss.”

Rabinowitz cautioned about accurate comparison numbers and said that the 120 dB limit represents the peak output reached at any frequency with a tone burst, and not the A-weighted level. He said “…the devices are spending very little time at [the upper] levels. Yes, there may be music and peak [acoustic] events that are there, but the actual exposure levels are well below [120 dB].” He also noted that the European Union’s limit for headphones of 85 dBA soundfield is roughly equivalent to 100 dBA in a very prescribed testing procedure. When you translate that 100 dBA number, Rabinowitz says it ends up being approximately 117 dB OSPL in a 2cc coupler. “That doesn’t mean you can play music anywhere near 117 dB; you can probably get the music to 103-105 dB.”

Although Rabinowitz agreed that procedures and measures for distortion, noise level, latency, and frequency bandwidth and smoothness would be useful, he argued the standard should not include frequency response characteristics. “[Regulation of] frequency response characteristics I would ditch because many of these devices have a plethora of frequency responses that they can achieve (potentially) with the controls they may have,” he said. Unwinding the numbers in an attempt to provide consumers with a meaningful gauge for assessing the devices is unlikely to produced anything of value. “[Relative to] the idea of a working group or ANSI,” says Rabinowitz, “I will reiterate that the ANSI measurements are a prescription for a huge list of things you need to measure, but there are no limits at all that have to be met. So, I think having a few [manufacturing] limits makes sense, [but with] a lot of the other things it isn’t clear to me what value they add…I think requiring a lot of measurements when we don’t have clear indications for what [differences] they actually make is what we should be careful about.” Zapala agreed with Rabinowitz, but emphasized that output measures remained a great concern, as they have the potential to cause hearing damage.

The impact of input-output compression can also make a big difference in the safety of hearing devices while weeding out poor products, noted David Fabry, PhD, of GN Hearing. He suggested it may be wise to mandate some form of input compression with a volume control to ensure that, at a 120 dB SPL, consumers at least have the ability to turn down the volume when sound levels become uncomfortable. “There is some evidence in the [MarkeTrak] satisfaction and benefit literature…that we saw the biggest increases in satisfaction…when we began to migrate away from peak-clipping, and move from linear processing to non-linear processing…When the K-Amp and the early WDRC devices were introduced, people could wear them in noise comfortably…”

Fabry also pointed out that the FDA started classifying hearing aids as Class II medical devices when their wireless technology risked interference with pacemakers and other medical devices. Now, with the potential for an OTC classification, either the FDA should have the same oversight for OTC devices using wireless technology or remove the Class II requirements for hearing aids.

Thomas Powers, PhD, an audiology consultant for Siemens/Sivantos, noted the importance of requirements governing the length and fastening/integrity of eartips in all hearing devices. “I don’t know too many consumers who would really know where the bony part of the cartilaginous portion of the ear canal is,” said Powers. “I say that a little facetiously, but the issue here is that we aren’t going to know how far people are putting [the eartips] in, and maybe the criteria should be that the tips themselves are defined by the specific length—say, 18 mm or whatever—which we assume would only go [halfway into] an average ear canal…They should also be configured in such a way that they’re not going to fall off. We know…from RIC devices when they first came out we had a lot of people with eartips in their ears.”

Recognizing the Moment

Despite the technical nature of many of the discussions, a lot of talk continually circled back on the problem of increasing consumer and physician awareness of hearing health and the benefits of better hearing. Ongoing collaborations of the four working groups were encouraged on the subjects of 1) Public Awareness and Consumer Measures; 2) Quality Metrics and Health Professional Education; 3) Innovation in Services–Access and Affordability; and 4) Consumer Comparison–Evaluation Criteria and Standardized Terminology.

Barbara Kelley and Margaret (Meg) Wallhagen of the Hearing Loss Association of America, presented Committee Chair Dan Blazer, MD, PhD, with the James B. Snow, Jr, MD Award—HLAA’s highest honor—for his leadership. Dr Blazer, who is well known for his work in geriatric psychology, emphasized that he accepted the award on behalf of the entire Committee. He said that their work and interactions with stakeholders opened his eyes to many new issues related to seniors and adults struggling with hearing loss.

At the meeting’s conclusion, Blazer emphasized that now is the time to advance the cause of better hearing. “This topic is now getting some attention,” said Dr Blazer. “and it’s getting attention outside the area of people affected by or working in the area of hearing loss. That’s a momentum that can be lost very quickly unless you keep pushing it. So I would encourage you to not let this drop. This is moment of opportunity [for advocating for better hearing care], given our report, given the PCAST report, given some of the things in the newspapers, given the [OTC] legislation—this is the opportunity to get things going.”

Listen to the meeting yourself. The audio recording of the dissemination meeting, as well as the meeting agenda, is available under the “Other Meeting Resources” section at: https://goo.gl/i1Wyzb —KES

Karl Strom is editor of The Hearing Review and has been reporting on hearing healthcare issues for 25 years.